[Detail] The Grand Canyon. Clarence E. Dutton, 1882.

Collection Overview

Mapping the National Parks, a subset of Map Collections: 1500-2004, contains approximately 200 maps dating from the 17th century to the present. This collection documents the history, culture, and geological formations of areas that eventually became United States National Parks. The collection is particularly strong in early maps of the Acadia, Grand Canyon, Great Smoky Mountains, and Yellowstone National parks.

Special Features

These online exhibits provide context and additional information about this collection.

- Maps of Acadia National Park

- Maps of Grand Canyon National Park

- Maps of Great Smoky Mountains National Park

- Yellowstone, the First National Park

For more ideas in exploring this collection, see the Collection Connection for Map Collections: 1500-2004.

Historical Eras

These historical era(s) are best represented in the collection although they may not be all-encompassing.

- Colonial Settlement, 1492-1763

- The American Revolution, 1763-1783

- The New Nation, 1780-1815

- Expansion and Reform, 1801-1861

- The Civil War and Reconstruction, 1850-1877

- Development of the Industrial United States, 1876-1915

- Emergence of Modern America, 1890-1930

- The Great Depression and World War II, 1929-1945

- Postwar United States, 1945-early 1970s

Related Collections and Exhibits

These collections and exhibits contain thematically-related primary and secondary sources. Also browse the Collection Finder for more related material on the American Memory Web site.

- American Environmental Photographs, 1891-1936

- American Landscape and Architectural Design, 1850-1920

- Built in America, 1933-Present

- California as I Saw It: First Person Narratives, 1849-1900

- Evolution of the Conservation Movement, 1850-1920

- Taking the Long View: Panoramic Photographs, 1851-1991

- Touring Turn-of-the-Century America, 1880-1920

Other Resources

Recommended additional sources of information.

- A Brief History of Mapping the National Parks

- Documentary Chronology of Selected Events in the Development of the American Conservation Movement, 1847-1920

Search Tips

Specific guidance for searching this collection

Search for National Park maps using the keyword search, keeping the selection set on "Search National Park Maps ONLY". (Otherwise, you will search all the map collections.)

To find items in this collection, search by Subject Index, Creator Index, or Title Index. To find maps by location, use the Geographic Location map of park sites or the Geographic Location Index.

For help with search words, go to the Around the World in the 1890s Subject Index.

For help with general search strategies, see Finding Items in American Memory.

U.S. History

The resources in Mapping the National Parks provide students information from a broad span of American history. An overview of this history is provided in the special presentations about the four national parks featured in the collection: Acadia, Grand Canyon, Great Smoky Mountains, and Yellowstone. Students can use the collection's maps to study the sociological significance of landscape, as well as a variety of historical topics pertaining to the settlement and expansion of America. In doing so, they will learn to derive maximum meaning from maps by considering them as products of the time period and culture in which they were created.

1) The Landscape

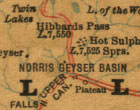

Radar mosaic, Yellowstone National Park, 1968. This map includes a press release from the Department of the Interior explaining the capabilities of radar to assist in mapping.

To understand a people - their economic, social, political and cultural systems - sociologists often begin by studying the physical landscape. The terrain, climate, natural resources, proximity to other people, and other geographic features influence nations in both obvious and subtle ways. Mapping the National Parks provides resources to assist students in their understanding of the development of America from a sociological perspective.

Search the collection on topography and geology to retrieve topographic maps of the national parks. Students can start by answering the questions below to become comfortable working with and understanding what these maps tell us about the physical landscape.

- What are the dominant physical characteristics and features of the landscape?

- What are the highest and lowest elevations?

- What are the names of rivers, lakes and streams in this area?

- What are the names of towns in this area?

- Where is the land located within the United States? Therefore, what do we know about the climate?

Arizona, 1962.

After answering these questions, ask students to consider how these features may have influenced the people living in these lands. For example, what was the influence of natural resources on housing, or the influence of climate on farming and thus economics? Or, in the case of Yellowstone and the Grand Canyons, students may find that the physical landscape may have precluded much habitation. As students continue using maps to study U.S. History, return to this discussion of how landscape influences history.

To assist in visualizing what the data on topographic maps represents, students may want to look at photographs and images of the national parks. Search on the names of the parks in these online collections:

- American Environmental Photographs, 1891-1936

- American Landscape and Architectural Design, 1850-1920

- Built in America, 1933-Present

- Evolution of the Conservation Movement, 1850-1920

- Taking the Long View: Panoramic Photographs, 1851-1991

- Touring Turn-of-the-Century America, 1880-1920

Students can also find additional information about these parks by visiting the National Park Service website.

2) Native Americans

Native Americans were the first people to name, live in, and use the lands of the national parks represented in this collection. For example, the Cherokee settled what is now the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. They considered this land the ancestral home of the entire Cherokee Nation. Students can use these maps to see evidence of the existence and influence of Native American tribes and cultures and to trace the movement of these people from their homelands to reservations. Students can begin by searching on the keyword phrase early maps to retrieve the oldest maps in the collection. Look for the cartographers' indications of where Native Americans lived and place names that were assigned by Native Americans. For additional maps, students can search across Map Collections, 1500-2004 on Indian.

This map of North America, 1715.

These maps indicate the influence of Native American culture on the settlement, naming, and mapping by European colonists. They can be used as the basis for a class discussion about what information European explorers might have gained from Native Americans. For example, the native peoples might have known routes through treacherous lands and where to find needed resources, such as drinking water and food. What else can you determine, using the maps and your imagination, about Native Americans and their influence upon the settlement of the United States?

The 1884 map entitled Map of the former territorial limits of the Cherokee "Nation of" Indians can provide the basis for a discussion of the movement of Native Americans to reservations. Search on Indians of North America to find this map, and note its second title, Map showing the territory originally assigned Cherokee "Nation of" Indians. Students can compare the locations of today's Native American reservations with these original land designations. Have the locations changed? How have the boundaries changed?

3) Early European Settlers

When Europeans first arrived between 1492 and the mid-1700s in what is now North America, they created maps of their new discovery. These maps were brought back to their homeland to report on what they found and to assist followers in navigating the routes to their discoveries.

Have students retrieve examples of these maps by searching on the keyword phrase early works to 1800. Many of the maps highlight coastal features. What does this suggest about the extent and methods of exploration? What else do these maps reveal about exploration?

Have students identify what resources are highlighted on the maps. Some maps include creative interpretations of unexplored territories. Students can look for examples of this uncertainty in the inaccurate size and shapes of continents and bodies of water. Students can also see what boundaries are shown.

- Do these boundaries look similar to those on today's maps of the United States?

- What can one learn from these boundaries about who controlled the land in North America at the time of the maps' creation?

For additional maps of European settlement , students can browse the Title Index of the Discovery and Exploration section of Map Collections, 1500-2004.

4) Treaty of Paris

In 1782, the British government decided to pursue peace with America to end the American Revolutionary War. Benjamin Franklin, John Adams and John Jay represented America at the negotiations in Paris. To locate boundaries and settle the war, the negotiators turned to John Mitchell's 1755 map titled A map of the British and French dominions in North America. Students can view this historical map and use the following questions to gain a better understanding of the dispute, of colonization and other issues of the time.

- What states now exist in the dominions that belonged to the British and the French in 1755?

- What can you learn from this map about how these states might have been influenced by their original British and French dominion?

- What information would the negotiators in Paris have used from the map?

- Are there obvious inaccuracies in the map? How might that have affected the decisions made at the treaty negotiations?

- What additional resources do today's negotiators have when settling boundary disputes?

5) Westward Expansion

The mid-1800s saw a boom of map production as Americans and arriving immigrants moved west. Miners were unearthing gold. The Mexican War ended adding Texas, California, and land in what is now southern Arizona and New Mexico to the United States. Railroad lines were being constructed.

Use the Geographic Location map to browse maps of Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon created in this era. The maps will provide students an idea of what settlements existed. They can look for travel routes and discuss what frontiers people might have encountered.

For additional maps of this era, students can browse the Title Index of the map collection Railroad Maps, 1828-1900.

6) National Parks in the Progressive Era

Between the American Civil War and World War I, America became an urban and industrialized country, moving away from its rural origins. So many people moved to the cities so quickly, there was often not adequate resources to house and govern everyone. Factories consumed natural resources, creating pollution as well as products. And a new kind of labor force was created to fuel industrial mass production. In response to these changes, labor and reform movements were organized to combat the ills of this new America.

Land of the Sky, 1917.

As people witnessed industry's depletion of natural resources and the destruction of landscapes, a conservation movement developed. For an overview of the development of this movement, students can read the Documentary Chronology of Selected Events in the Development of the American Conservation Movement, 1847-1920 in the collection The Evolution of the Conservation Movement. They will learn that the first National Park, Yellowstone, was created during the Progressive Era in 1872. Students can use the Geographic Location map to browse maps of Yellowstone and consider the role of this national park during this era of urban and industrial growth. What did Yellowstone offer people exhausted by city life? How might they have traveled to Yellowstone at the turn of the century?

In this era leisure time became popular. People looked to leave the cities and enjoy the "country." Many set off in the increasingly-affordable cars to vacation in what would become parklands. Students can find evidence of this development by searching the collection on tourist and recreation and National Park Service to see examples of the maps provided hikers and vacationers. This search will retrieve modern maps of the parks created by the National Park Service that highlight tourist resources such as information centers, hiking trails, and roads.

7) Tennessee Valley Authority

In 1933, the U.S. Government created the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), a New Deal program under President Franklin D. Roosevelt's administration. Through this program many people were employed during the Great Depression, assisting in the building of dams to create electricity and to control flooding of the valley.

This initiative expedited mapping of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park because the park is within the Tennessee River watershed. Students can use the Geographic Location map to browse maps of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Teachers can facilitate a discussion about the value of the TVA, its influence on the National Park, and how it might have affected the lives of those living in the valley. What were the benefits and costs of this project? If it were your job to approve New Deal projects, would you have approved the TVA? Why or why not? Inform the discussion by searching across all the American Memory collections on Tennessee Valley Authority to find other artifacts related to this project. Other New Deal programs are featured in these online collections:

- America from the Great Depression to World War II: Photographs from the FSA and OWI, ca. 1935-1945

- American Life Histories: Manuscripts from the Federal Writers' Project, 1936 - 1940

- The New Deal Stage: Selections from the Federal Theatre Project, 1935-1939

- Voices from the Dust Bowl: the Charles L. Todd and Robert Sonkin Migrant Worker Collection, 1940-1941

Critical Thinking

Through the study of Mapping the National Parks students can build historical-thinking skills. They can compare maps of the same area to look for change over time, or they can do an in-depth study of the relationship between land-ownership and the creation of the United States. The collection's maps can also be used to learn sophisticated analysis and interpretation skills and to grapple with the issue of property rights. Finally, the collection can instigate research into national parks and related uses of land.

Chronological Thinking

Chart of the coast of Maine, 1837.

Explorers, cartographers, government officials and others have gathered data about the land that became national parks from the time before it was designated as park land to the present day. By comparing maps of the same land area made at various dates, students can investigate how the land changed as well as how the information gathered about this land changed over time. For example, search on Maine to retrieve the maps of this state and of the Acadia National Park. Students can view the maps in chronological order, looking for the similarities and differences among the maps.

From their observations, students can also determine what technological advances may have assisted the data collectors. For example, look at different ways cartographers represented topography. In early maps, cartographers represented mountains with circles of small lines. Later, a system was standardized using topographic lines to indicate more exact elevation.

Also available in Mapping the National Parks are chronologically arranged collections of topographic quadrangle maps of Tennessee and North Carolina at a scale of 1:24,000. Students can look at these highly detailed maps of small regions of the parks and look for change over time. Note that items drawn in purple represent new developments from previous versions of the same map. To see how these quadrangles fit together, view the Topographic Quadrangle Map section of the special presentation Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Historical Comprehension

Through this collection, students may gain an understanding of the evolution of land ownership in North America and its relation to the development of a nation of united states. To begin, they can browse the Title Index or Geographic Location Index to get a sense of the land itself. Images of the land can enhance one's use of these maps, and may be found by searching on the names of places depicted in the maps, in American Memory's photographic and print collections. Next, they can browse the Special Presentations and search the maps on Indian for information about the first inhabitants of the land. This too can be enhanced with searches on Indian in American Memory.

Next, students can browse the Title Index and Special Presentations and search the collection on exploration and route for information about the stages of exploration that changed the ownership and use of the land for over three centuries. Searching explorer in Pioneering the Upper Midwest locates journals and narratives by explorers that bring another dimension to their study. Students can better understanding the related topic of colonization by using the 1755 map used by the negotiators at the treaty of Paris. With this map, they can also learn about the role of war in changing the ownership of land and therefore a nation's boundaries. Searching on Mexican war in American Memory, students may learn about that conflict and its impact on the development of the United States.

By searching on territory and state, students can find evidence of the manner in which the United States grew. Searching on slave and secession, in Civil War Maps, students can get a feel for the importance of states and territories to the Civil War conflict, and the precarious state of the nation before the war, reflected in changing map boundaries and designations of loyalties.

While the United States has for all intents and purposes ceased to grow, the use of its land continues to change. What other changes of land use and ownership are evidenced in the collection's maps? What do these changes suggest about the people who inhabit the land, their government, society, and values?

Historical Analysis and Interpretation

Cartographers created the national park maps for a variety of purposes and goals. Some maps had one specific goal, while many had multiple intended functions. The cartographers' goals reflect what was going on in that period of American history. Therefore, in addition to information about the land it depicts, a map also provides information about the creator's goals and the historical background that informed the map's creation. Teachers may use this collection to help students to access this level of meaning in their analysis and interpretation of maps, which can also be applied to other historical artifacts, including literature.

Students can choose an era in American history and browse the collection by Geographic Location to find maps that existed at that time. They can use the questions below to determine the cartographers' goals and the events of that period:

- Who made the map? Was this person a government employee? Hired by a private company? Self-employed? What assumptions can we make about the map from this knowledge?

- What is the most prominent feature of the map? For example, is it transportation routes? Boundaries and land ownership? Topography?

- Why would a map with these details be needed at the time it was made? Was the country at war? What form of transportation was most commonly used? Was the park easily accessible to the average citizen?

- How might the cartographer have been trying to influence people's perception of the land? Why might he have tried to affect their perception in this way? Was he effective?

Historical Issue-Analysis and Decision-Making

Mapping the National Parks provides students an opportunity to study the issue of landownership and property rights. By reading the special presentations about the four parks featured in this collection, Acadia, Grand Canyon, Great Smoky Mountains, and Yellowstone, students will learn who owned and controlled these lands prior to their becoming national parks. Trace the land's history from Native Americans to European settlers to Americans to the federal government. Explore the following questions in a class discussion:

- What does it mean to own the land? How might different cultures understand landownership?

- How do people and nations assert their claim to land?

- What are the different ways landownership transfers from one person to another?

America noviter delineata, 1640?.

Continue the discussion by asking students to consider how they would react to the federal government designating land they owned to be a national park. Would they object? Would they demand certain compensation? Introduce the concept of eminent domain, defined by Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary as:

a right of a government to take private property

for public use by virtue of the superior dominion of the sovereign

power over all lands within its jurisdiction.

The U.S. Government uses the right of eminent domain for power lines, damns and other public utilities. Search on the phrase eminent domain in THOMAS, legislative information online, to find current examples of the government's use of this right.

Historical Research Capabilities

America has national parks, national monuments, national forests, and state, county, and local-level versions of these entities. Maps from this collection instigate research into the definitions and regulations governing these entities. What are the similarities and differences in how they are maintained? Funded? Regulated? How does their designation determine how the land is used by different "stake holders" such as the government, miners, loggers, hunters, and vacationers? How do the different entities reflect different uses and different significance for Americans?

Students can research and discuss what factors contribute to a land being designated a national park as opposed to a national monument or forest. They can use the parks featured in this collection as a starting point. Begin by reading the special presentations about the four parks featured in the collection: Acadia, Grand Canyon, Great Smoky Mountains, and Yellowstone. Continue the research by searching the collection by park name to find maps that feature the characteristics that led to the parks becoming national parks, as opposed to other uses.

Arts & humanities

Using Mapping the National Parks, students can improve their understanding of places and times in history while they develop their language arts skills. The collection's maps can form the basis for creative and expository writing activities, including travel writing, environmental essays, and biographies. Several maps can also be used to help students understand and interpret symbolism.

1) Travel Writing

Students can create a character from another time period who is traveling in the region of a national park featured in this collection. Is this person an early European explorer? A cartographer hired by the government or a private party? Or a frontiersman leaving family behind to seek out fortune and adventure?

Once the students have created their characters, they can browse the Subject Index to find a map that existed when this character would have lived.

Students can then use this map to write travel stories or essays for a specific audience. Is the character writing a book of adventure? A book to advise future travelers to the area? Or is he or she reporting back to the funder of the trip? Is he or she writing in a journal? Or letters home to family or friends? Imagining that they are travelling a route on the map, have students use place names and geographic features to give their writing detail. Does the character find the map to be accurate and useful? What modifications would the character have made to the map based on his or her discoveries?

To read other travelers' writings, students can search on author Mark Twain or names of western states in the collection California as I Saw It: First Person Narratives, 1849-1900.

2) Environmental Essay

Yellowstone National Park, 1910.

Conservationist John Muir described the beauty of America's landscapes in essays and books. His writings were an important influence in the conservation movement. Have students read his description of Yellowstone beginning on page 37 of Our National Parks, 1901 from the collection Evolution of the Conservation Movement, 1850-1920.

...[Yellowstone National Park] is full of exciting wonders. The wildest geysers in the world, in bright, triumphant bands, are dancing and singing in it amid thousands of boiling springs, beautiful and awful, their basins arrayed in gorgeous colors like gigantic flowers; and hot paint-pots, mud springs, mud volcanoes, mush and broth caldrons whose contents are of every color and consistency, splash and heave and roar in bewildering abundance. In the adjacent mountains, beneath the living trees the edges of petrified forests are exposed to view, like specimens on the shelves of a museum, standing on ledges tier above tier where they grew, solemnly silent in rigid crystalline beauty after swaying in the winds thousands of centuries ago, opening marvelous views back into the years and climates and life of the past. Here, too, are hills of sparkling crystals, hills of sulphur, hills of glass, hills of cinders and ashes, mountains of every style of architecture, icy or forested, mountains covered with honey-bloom sweet as Hymettus, mountains boiled soft like potatoes and colored like a sunset sky.

Our National Parks, John Muir, 1901. Page 38.

After reading this excerpt, students can browse the maps of Yellowstone in the Geographic Location index. Can they find what section of the park Muir was describing? What are the names of those areas? Does one get the same sense of place from Muir's description as one does from viewing maps in the collection? What does one media portray that the other does not? Use these and the following questions in a class discussion.

- What imagery does Muir use to describe the park?

- How does Muir involve the reader's senses in his description? What do you see, hear and smell from his description?

- What image of the park does Muir portray? What emotions does he elicit from the reader?

- Does he intrigue you to want to visit the park?

- How does Muir make the reader feel this a unique place?

Students can search on the names of other national parks In Evolution of the Conservation Movement to read other descriptions. Searching on John Muir will retrieve additional works by the author as well as photographs.

3) Written Communication

The National Park Service provides visitors with maps that both inform visitors of the wonders of the park and warn them of possible dangers. Students can search on National Park Service to read the tourist information provided on several maps. They can use the maps to study the careful use of language that entices the curious while reminding people to be cautious. In addition, students will see how the language is appropriate for a vast variety of tourists who visit the parks. Have students answer the following questions to identify these written communication skills:

- What is the first or most prominent written information on the map? What is the effect of reading this first?

- What dangers is the visitor alerted to? Are they made to feel nervous about leaving their cars? How does the language used create that or any other feeling?

- To what sights are visitors directed? Is information provided for those who want to leave the heavily traveled areas? How are these people made to understand safety concerns associated with this exploration?

- What other types of information are represented on the map?

- What do you think were the goals of the national park in creating this text? Were the goals at odds with each other? What techniques and language were used to meet all of these goals at once?

4) Biography

Sheet IV - The Temples and Towers of the Virgen, Tertiary history of the Grand cañon district, 1882.

After reading the park histories in the four special presentations Acadia, Grand Canyon, Great Smoky Mountains, and Yellowstone, students can write biographies of individuals named in the text. Try searching the collection on the person's name to find maps related to his or her life. Have students conduct further research on the lives and experiences of the individual. Try searching the names in all of the American Memory collections. They can illustrate the biographies with maps from the collection that represent places the individual traveled through or lived in.

5) Symbolism

Several of the maps contain symbolic drawings, often surrounding the key or title, providing an opportunity to work with visual symbolism. Many of these maps are the oldest in the collection and may be accessed by searching early. Examine these drawings as a class and consider the following questions:

- What is the subject of the drawing? If there are people, who are they? Where are they? What are they doing?

- Does the drawing tell a story? Does it depict an event? An idea?

- What does the drawing add to the map? Why would a cartographer include this subject on this map? How does the drawing relate to the land being depicted? How does it relate to those who might have commissioned, made, or used the map?

- Who do you think was the map's audience? What would this audience have thought of the drawing?

- What do you think was the purpose of the map? How does the drawing relate to that purpose? Does the drawing serve any other purposes?

- Why aren't drawings included in maps today? What does this suggest about how people think of maps today? What does this suggest about how people used to think of maps?

Some of these drawings include graphic material and ought to be used with older students at a teacher's discretion. Younger students may study symbolism using the map on the right.

This map represents the cartograher's perspective of the United States. Have students consider the following questions:

- Why did the cartographer choose to use the image of an eagle? How would viewers of the map respond to this image? Is it an image of strength?

- What were the political, economic and social issues at the time the map was published?

- What message does the cartographer's interpretation of the country depict?