| |

|||

|

|

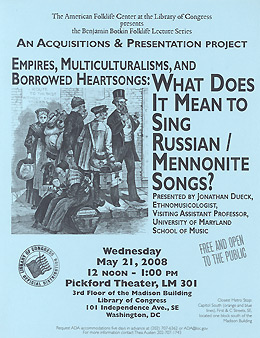

The American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress May 21, 2008 Event Flyer Empires, Multiculturalisms, and Borrowed Heartsongs:

|

|

It’s often said that music is never new, but always borrowed. But borrowings can be as full of feeling, as meaningful, and as politically important as “the real thing. ”This paper juxtaposes these aspects of musical practice (historically situated borrowing, and emotional investment in society) by retelling the story of Russian Mennonite choral music. As “colonists” in nineteenth-century Russia, Mennonites sang German diasporic choral musics and borrowed Russian choral musics; when war drove many to North America, Mennonites drew on this repertoire and borrowed new repertoires to forge links to a new élite: North American classical choral singing circles. This paper traces this story not as linear narrative, but as genealogical fragments, beginning with the resonances of particular songs for present-day Mennonite writers, historians, and singers; and then exploring past moments of the production and reception of these songs in Russia and North America.

It’s often said that music is never new, but always borrowed. But borrowings can be as full of feeling, as meaningful, and as politically important as “the real thing. ”This paper juxtaposes these aspects of musical practice (historically situated borrowing, and emotional investment in society) by retelling the story of Russian Mennonite choral music. As “colonists” in nineteenth-century Russia, Mennonites sang German diasporic choral musics and borrowed Russian choral musics; when war drove many to North America, Mennonites drew on this repertoire and borrowed new repertoires to forge links to a new élite: North American classical choral singing circles. This paper traces this story not as linear narrative, but as genealogical fragments, beginning with the resonances of particular songs for present-day Mennonite writers, historians, and singers; and then exploring past moments of the production and reception of these songs in Russia and North America.

Think of the singing of a suffering people, an exiled people, a people in hiding; remember devastated villages, lost lands, lost ancestors. Mennonites participated in populist Russian German Saengerbunds (“choral societies”), and also borrowed Russian choral musics, uttering links to diasporic subculture and superculture. But when economic push factors, war, and finally revolution descended upon them, many moved to North America. Those who remained attempted to continue their institutional and musical lives as before, but had to contend with unfriendly, new, state-sponsored cultural and religious policies. During the Stalinist period, many Mennonites (and many more Russian Germans) suffered terribly; memoirs of these Mennonites describe the unbearably tragic circumstances of their lives, and German hymns as lifelines of Mennonite collective memory. Not surprisingly, for North American Russian Mennonites, the “Russian-ness” of Mennonite music is a traumatic aporia marked by these (borrowed, translated) songs, which, for many, narrate a Mennonite Exodus story. This memory is not without instrumentality, though; cultural politics of both victimhood and apology are increasingly important ways of legitimating ethnic identities, nationally and globally.

And think of immigrant pioneers, of homesteads, of building new cities, becoming a resounding part of the great cultural braid of the New World. In Canada, Mennonites found new political and cultural institutions and meanings to contend with: the Canadian educational system and its Anglophone choral traditions, and a post-1960s Canadian multiculturalism that relativized divides in the Canadian nationstate. Mennonites continued their Russian-German tradition of Saengerfests (“choral festivals”), and founded Mennonite colleges which, as parts of Canadian universities, nurtured Mennonite singers and conductors who came to prominence in Canadian classical music circles. Mennonites also began to understand themselves as “ethnic,” and, partly in response to Canadian government funding, developed institutions that nurtured self-consciously Mennonite writers, poets, and composers, who in turn wrote novels, poems, and songs. But these newly ethnic texts, while they drew on histories and repertoires claimed by Russian Mennonites, had also to speak the language of a national discourse of Canadian ethnicities, placing themselves relative to what became a dominant (though benevolent) Anglo center.

This fractured story reminds us, then, that borrowings and complicities need not be “inauthentic” but are instead links showing the emotional investment of ethnic performers in their socio-musical surroundings, and in their remembered (and imagined) histories.

The American Folklife Center was created by Congress in 1976 and placed at the Library of Congress to "preserve and present American Folklife" through programs of research, documentation, archival preservation, reference service, live performance, exhibition, public programs, and training. The Center includes the American Folklife Center Archive of folk culture, which was established in 1928 and is now one of the largest collections of ethnographic material from the United States and around the world. Please visit our web site.

| ||||