Introduction and Biology of Influenza

Influenza Prevention and Control Recommendations

On This Page

Published for the 2010-11 Influenza Season; Adapted for the 2012-13 Influenza Season

Introduction

In the United States, annual epidemics of influenza occur typically during the late fall through early spring. Influenza viruses can cause disease among persons in any age group, but rates of infection are highest among children. During these annual epidemics, rates of serious illness and death are highest among persons aged 65 years and older, children aged younger than 2 years, and persons of any age who have medical conditions that place them at increased risk for complications from influenza. Influenza epidemics were associated with estimated annual averages of approximately 36,000 deaths during 1990--1999 and approximately 226,000 hospitalizations during 1979--2001. An August 27, 2010 MMWR report “Estimates of Deaths Associated with Seasonal Influenza – United States, 1976-2007” has updated information regarding estimated deaths associated with seasonal influenza.

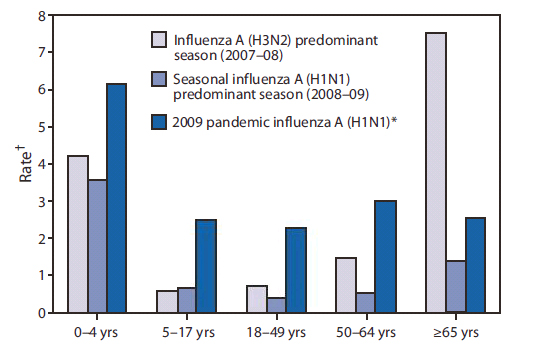

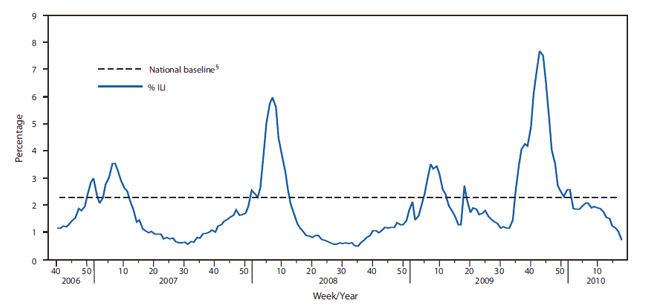

Influenza A virus subtypes that are generated by a major genetic reassortment (i.e., antigenic shift) or that are substantially different from viruses that have caused infections over the previous several decades have the potential to cause a pandemic. In April 2009, a novel influenza A (H1N1) virus, 2009 influenza A (H1N1), that is similar to but genetically and antigenically distinct from influenza A (H1N1) viruses previously identified in swine, was determined to be the cause of respiratory illnesses that spread across North America and were identified in many areas of the world by May 2009. Influenza morbidity caused by 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) remained above seasonal baselines throughout spring and summer 2009 and was the cause of the first pandemic since 1968. In the United States, the pandemic was characterized by a substantial increase in influenza activity, as measured by multiple influenza surveillance systems, that was well beyond historical norms in September 2009, peaking in late October 2009, and returning to seasonal baseline by January 2010 (Figures 1 and 2) . During this time, more than 99% of viruses characterized were the 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus. Data from epidemiologic studies conducted during the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic indicate that the risk for influenza complications among adults aged 19--64 years who had 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) was greater than typically occurs for seasonal influenza. Information about the 2011-12 season is available in the MMWR article Update: Influenza Activity – United States, 2011-12 Season and Composition of the 2012-13 Influenza Vaccine.

Influenza viruses undergo frequent antigenic change as a result of point mutations and recombination events that occur during viral replication (i.e., antigenic drift). The extent of antigenic drift and evolution of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus strains in the future cannot be predicted. However, 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus strains continue to circulate among people worldwide in a pattern similar to other seasonal influenza A and B virus strains. 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus is now referred to as influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus, or 2009 H1N1 virus.

Annual influenza vaccination is the most effective method for preventing influenza virus infection and its complications. Annual vaccination with the most up-to-date strains predicted on the basis of viral surveillance data is recommended. Influenza vaccine is recommended for all persons aged 6 months and older who do not have contraindications to vaccination. Trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (TIV) can be used for any person aged 6 months and older, including those with high-risk conditions (Box). Live, attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) may be used for healthy nonpregnant persons aged 2--49 years. No preference is indicated for LAIV or TIV when considering vaccination of healthy nonpregnant persons aged 2--49 years. Because the safety or effectiveness of LAIV has not been established in persons with underlying medical conditions that confer a higher risk for influenza complications, these persons should be vaccinated only with TIV. Although vaccination coverage has increased in recent years for many groups recommended for routine vaccination, considerable room for improvement remains, and strategies to improve vaccination coverage in the medical home and in nonmedical settings should be implemented or expanded. Information about vaccine coverage among different populations during the 2011-2012 season can be found at Reports on Flu Vaccine Coverage and Utilization.

Information about vaccine coverage among health care personnel during the 2010-11 season can be found in the MMWR article Influenza Vaccination Coverage Among Health-Care Personnel --- United States, 2010-11 Influenza Season. Information about vaccine coverage among pregnant women during the 2010-11 season can be found in the MMWR article Influenza Vaccination Coverage Among Pregnant Women --- United States, 2010-11 Influenza Season.

Antiviral medications are an adjunct to influenza vaccination and are effective when administered as treatment and when used for chemoprophylaxis after an exposure to influenza virus. However, the emergence since 2005 of resistance to one or more of the four licensed antiviral agents (oseltamivir, zanamivir, amantadine, and rimantadine) among circulating strains has complicated antiviral treatment and chemoprophylaxis recommendations. CDC has revised recommendations for antiviral treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza periodically in response to new data on antiviral resistance patterns among circulating strains and risk factors for influenza complications. With few exceptions, 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus strains that began circulating in April 2009 have remained sensitive to oseltamivir and zanamivir, but resistant to amantadine and rimantadine. Visit FluView for the latest CDC surveillance data on antiviral drug resistant influenza viruses and the Antiviral Drugs page on CDC’s Influenza web site for the latest antiviral drug treatment and chemoprophylaxis recommendations .

Biology of Influenza

Influenza A viruses are found in humans and many different animals, including ducks, chickens, pigs, whales, horses and seals.

See Other Flu Web Sites for more information.

Influenza A and B are the two types of influenza viruses that cause epidemic human disease. Influenza A viruses are categorized into subtypes on the basis of two surface antigens: hemagglutinin and neuraminidase. During 1977--2011, influenza A (H1N1) viruses, influenza A (H3N2) viruses, and influenza B viruses have circulated globally. Information about the 2012-2013 season can be found in the weekly FluView. Information about the 2011-12 season can be found in the MMWR article Update: Influenza Activity – United States, 2011-12 Season, and Composition of the 2012-13 Influenza Vaccine. Influenza A virus subtypes and B viruses are separated further into groups on the basis of antigenic similarities. New influenza virus variants result from frequent antigenic change (i.e., antigenic drift) caused by point mutations and recombination events that occur during viral replication. Recent studies have explored the complex molecular evolution and epidemiologic dynamics of influenza A viruses.

New or substantially different influenza A virus subtypes have the potential to cause a pandemic when they are able to cause human illness and demonstrate efficient human-to-human transmission and when little or no previously existing immunity has been identified among humans. In April 2009, human infections with a novel influenza A (H1N1) virus were identified, and this virus subsequently caused a worldwide pandemic. The 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus was derived from influenza A viruses that have circulated in swine during the past several decades and is antigenically distinct from human influenza A (H1N1) viruses in circulation since 1977. The 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N) virus contains a combination of gene segments that had not been reported previously in animals or humans. The hemagglutination (HA) gene, which codes for the surface protein most important for immune response, is related most closely to the HA found in contemporary influenza viruses circulating among pigs. This HA gene apparently evolved from the avian-origin 1918 pandemic influenza H1N1 virus, which is thought to have entered human and swine populations at about the same time.

Currently circulating influenza B viruses are separated into two distinct genetic lineages (Yamagata and Victoria) but are not categorized into subtypes. Influenza B viruses undergo antigenic drift less rapidly than influenza A viruses. Influenza B viruses from both lineages have circulated in most recent influenza seasons. Information about the 2012-2013 season can be found in the weekly FluView.

Immunity to surface antigens, particularly hemagglutinin, reduces the likelihood of infection. Antibody against one influenza virus type or subtype confers limited or no protection against another type or subtype of influenza virus. Furthermore, antibody to one antigenic type or subtype of influenza virus might not protect against infection with a new antigenic variant of the same type or subtype. Frequent emergence of antigenic variants through antigenic drift is the virologic basis for seasonal epidemics and is the reason for annually reassessing the need to change one or more of the recommended strains for influenza vaccines.

More dramatic changes, or antigenic shifts, occur less frequently. Antigenic shift occurs when a novel influenza A virus causes human infection and can result in the emergence of a novel influenza A virus with the potential to cause a pandemic if the novel virus is capable of sustained human-to-human transmission. The 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus was not a new subtype when it emerged in 2009, but because most humans had no pre-existing antibody to key pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus hemagglutinin epitopes, widespread transmission was possible. The 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus is now referred to as influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus, or 2009 H1N1 virus.

Influenza viruses expected to be circulating among people worldwide during 2012-2013 include influenza A (H3N2), 2009 H1N1, B (Yamagata lineage) and B (Victoria lineage) viruses.

FIGURE 1. Cumulative rate of hospitalizations during three influenza seasons, by age group --- Emerging Infections Program, United States, 2007--2010

* 2009 Pandemic Influenza A(H1N1) hospitalization data from September 1, 2009--January 21, 2010.

† Per 10,000 population.

FIGURE 2. Percentage of visits for influenza-like Illness (ILI)* reported by the U.S. Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet),† by surveillance week --- United States, October 1, 2006--May 1, 2010

* ILI is defined as fever (temperature of 100°F or more [37.8°C or more) and a cough and/or a sore throat in the absence of a known cause other than influenza.

† ILINet consists of approximately 2,400 health-care providers in 50 states reporting approximately 16 million patient visits each year.

§ The mean percentage of visits for ILI during noninfluenza weeks for the previous three seasons plus two standard deviations. A noninfluenza week is a week during which <10% of specimens tested positive for influenza.

Contact Us:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

1600 Clifton Rd

Atlanta, GA 30333 - 800-CDC-INFO

(800-232-4636)

TTY: (888) 232-6348 - Contact CDC-INFO