This is a guest post by Bernice Ramirez. Bernice is working with the education team at the Library of Congress as part of the Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities (HACU) Internship Program.

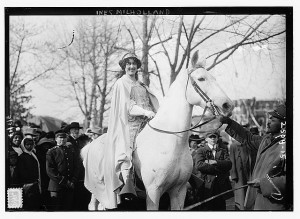

On March 3, 1913, lawyer Inez Milholland led several bands, colorful floats and thousands of demonstrators down Pennsylvania Avenue in a call for women’s suffrage. Primary sources from the Library of Congress can help students not only see the size and grandeur of this historic parade, but also go behind the scenes to examine the plans and promotional strategies of its organizers.

The march, a public demonstration for women’s right to vote, was envisioned by Alice Paul, an American trained in the militant British suffragist movement. After serving time in prison for picketing in London, Paul returned to the United States with plans to reinvigorate the national campaign to give women the right to vote. Paul made use of her activist training; the march was strategically organized on the day before President Wilson’s inauguration to take advantage of the publicity.

Paul also organized the procession of suffragists into key sections, with the section for representatives of countries that had enfranchised women leading the march. Students can use this diagram of the marching line to investigate the other sections. Ask students to consider why the groups were placed in where they were. Would students change any of the groups or their positions to make the marching line more effective?

The parade began smoothly on March 3, 1913, with the procession of suffragists advancing without interruption. The crowd around the march grew rapidly, however, and suddenly a large gathering of mostly men blocked the suffragists’ path. Accounts differ as to the level of hostility the demonstrators encountered, but many newspapers reported that the men shouted insults at the suffragists, some of whom were at times forced to walk single file through the crowds.

- Teachers can use the march’s official program to explore such questions as: What was the purpose of the procession? What did the procession showcase that other forms of protest could not?

-

- Teachers can have students read this article from the suffragist paper, Woman’s Journal, to explore how the media helped to spread the suffragists’ message. Teachers can ask students to consider the author’s point of view to answer: what is the author’s purpose? How would the article change if it were written from the perspective of an anti-suffragist watching the parade?

- The official program shows an illustration of Inez Milholland leading the march on a white horse. Students can compare the illustration with an actual photograph taken of Milholland at the parade. Who created each drawing and photograph? What did the artist and photographer try to convey? What is not shown? What would the photograph look like if it were in color?

- Students can compare the picture of the suffragist procession on March 3, 1913 and one of the same city during President Wilson’s inauguration held the next day. Teachers can ask students to describe what they see in each and predict what will happen next. What kinds of people are in each photograph? Why is the crowd at the inauguration more orderly?

For more primary sources, background information and teaching ideas, try the Library’s Women’s Suffrage Primary Source Set.

The march of 1913 is remembered as a major victory that helped gather national sympathy for the suffragist movement. What are some current issues that have benefited from similar large demonstrations?