What are cells?

Cells are the structural and functional units of all living things, from microorganisms to humans, and they are considered the smallest form of life. Cells house the biological machinery that makes the proteins, chemicals and signals responsible for everything happening inside our bodies.

Cells are the structural and functional units of all living things, from microorganisms to humans, and they are considered the smallest form of life. Cells house the biological machinery that makes the proteins, chemicals and signals responsible for everything happening inside our bodies.

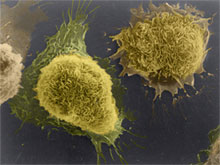

What do cells look like?

The size of a cell varies. Some of the smallest are unicellular bacteria, and some of the largest are found in plants. The biggest human cell, the egg, is about the same diameter as a hair strand. Cells also come in different shapes—round, flat, long, star-like, cubed and even amorphous. Most cells are colorless and semi-transparent.

How many different types of human cells are there?

Our trillions of cells are organized into about 200 major types. All of a person’s cells contain the same set of genes, but these genes are “switched on” in different patterns that produce different proteins the cell needs to perform specialized tasks. For instance, red blood cells carry oxygen throughout the body, white blood cells kill germ invaders, intestinal cells release molecules that help digest food, nerve cells send chemical and electrical messages that produce thoughts and movement, and heart cells contract in unison to pump blood.

What are eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells and how are they different?

Eukaryotic cells, which are found in animals, plants, fungi and some single-celled organisms, have a number of internal structures, called organelles. The most prominent organelle is the nucleus, which contains the cell’s genetic material, DNA. Prokaryotic cells are found in bacteria and Archaea, which are both groups of single-celled microorganisms. These cells lack a nucleus and other organelles and tend to be smaller than eukaryotic cells

Eukaryotic cells, which are found in animals, plants, fungi and some single-celled organisms, have a number of internal structures, called organelles. The most prominent organelle is the nucleus, which contains the cell’s genetic material, DNA. Prokaryotic cells are found in bacteria and Archaea, which are both groups of single-celled microorganisms. These cells lack a nucleus and other organelles and tend to be smaller than eukaryotic cells

What are some of the major organelles in a human cell?

In addition to the nucleus, here are a few of the most prominent:

- Mitochondria, which convert energy from food into the body’s main energy source, adenosine triphosphate (ATP).

- Ribosomes, molecular factories that make proteins.

- The endoplasmic reticulum (ER), a network of interconnected sacs involved in processing newly made proteins and producing fatty substances called lipids.

- The golgi complex, which receives proteins and lipids from the ER, packages them, and sends them to their final destinations inside the cell, within the cell membrane or outside the cell.

- Lysosomes, where waste materials are broken down and disposed of or recycled.

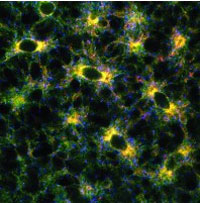

How do scientists study cells?

The ability to peer into the body at the cellular and subcellular levels has come a long way since British scientist Robert Hooke first described cells in the mid-1600s. Today, cell biologists rely on an array of imaging techniques to magnify organelles or track other components as cells divide, grow, interact and carry out other vital tasks. Scientists also can perform biochemical or genetic tests to study how cells respond to environmental stressors, such as rising temperatures or toxins, and they can use sophisticated computational tools to integrate and analyze all the data.

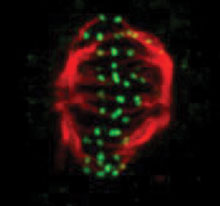

How do our bodies make more cells?

One cell divides into two in a process called mitosis, which produces two genetically identical "daughter" cells from a single "parent" cell. Another type of cell division, meiosis, generates four daughter cells that are genetically distinct from one another and from the original parent cell. Only a few special cells are capable of meiosis: those that will become eggs in females and sperm in males.

One cell divides into two in a process called mitosis, which produces two genetically identical "daughter" cells from a single "parent" cell. Another type of cell division, meiosis, generates four daughter cells that are genetically distinct from one another and from the original parent cell. Only a few special cells are capable of meiosis: those that will become eggs in females and sperm in males.

How and why do cells die?

Cells come equipped with the instructions and instruments necessary to self-destruct. This programmed cell death, or apoptosis, serves a healthy and protective role in our bodies. It helps shape our fingers and toes before birth, and it kills off diseased cells during our lives. Another kind of cell death, called necrosis, is unplanned and can result from a sudden traumatic injury, infection or exposure to a toxic chemical.

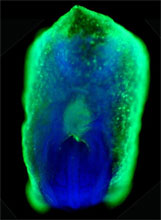

What are stem cells?

Stem cells have the potential to develop into many different cell types in the body. Embryonic stem cells can become just about any cell. Adult stem cells have more limited potential and can only form a particular tissue or organ. Induced pluripotent stem cells are mature adult cells reprogrammed to act like embryonic ones.

How do problems in cells lead to disease?

Genetic mutations that alter the cell’s ability to divide, make proteins, remove waste or perform other tasks can lead to conditions such as birth defects, cancer and metabolic diseases. Cells that undergo physical trauma or infection can, in extreme cases, contribute to harmful inflammation and organ malfunction.

Genetic mutations that alter the cell’s ability to divide, make proteins, remove waste or perform other tasks can lead to conditions such as birth defects, cancer and metabolic diseases. Cells that undergo physical trauma or infection can, in extreme cases, contribute to harmful inflammation and organ malfunction.

How does studying cells aid our understanding of human health and disease?

Learning more about how cells work—and what happens when they don’t work properly—teaches us about the biological processes that keep us healthy and sheds light on new ways to treat disease. Cellular research has already led to cancer therapies, antibiotics, cholesterol-lowering medicine and improved drug delivery systems. However, much more remains to be discovered, including how stem cells and certain other cells regenerate, which could offer insight on how to repair damaged or lost tissue.

Learn more:

Inside the Cell

Cell Biology Science Education Resources

NIGMS is a part of the National Institutes of Health that supports basic research to increase our understanding of life processes and lay the foundation for advances in disease diagnosis, treatment and prevention. For more information on the Institute's research and training programs, see http://www.nigms.nih.gov.

Content created December 2012