|

|

A Typology for Campus-Based Alcohol Prevention: Moving toward Environmental Management Strategies*

WILLIAM DeJONG, Ph.D.,† and LINDA M. LANGFORD,

Sc.D.†

Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Boston University School of

Public Health, 715 Albany Street, Boston, Massachusetts 02118

ABSTRACT. Objective: This article outlines a typology of programs

and policies for preventing and treating campus-based alcohol-related problems,

reviews recent case studies showing the promise of campusbased environmental

management strategies and reports findings from a national survey of U.S. colleges

and universities about available resources for pursuing environmentally focused

prevention. Method: The typology is grounded in a social ecological framework,

which recognizes that health-related behaviors are affected through multiple

levels of influence: intrapersonal (individual) factors, interpersonal (group)

processes, institutional factors, community factors and public policy. The survey

on prevention resources and activities was mailed to senior administrators responsible

for their school's institutional response to substance use problems. The study

sample was an equal probability sample of 365 2- and 4-year U.S. campuses. The

response rate was 76.9%. Results: Recent case studies suggest the value

of environmentally focused alcohol prevention approaches on campus, but more

rigorous research is needed to establish their effectiveness. The administrators'

survey showed that most U.S. colleges have not yet installed the basic infrastructure

required for developing, implementing and evaluating environmental management

strategies. Conclusions: The typology of campus-based prevention options

can be used to categorize current efforts and to inform strategic planning of

multilevel interventions. Additional colleges and universities should establish

a permanent campus task force that reports directly to the president, participate

actively in a campus-community coalition that seeks to change the availability

of alcohol in the local community and join a state-level association that speaks

out on state and federal policy issues. (J. Stud. Alcohol, Supplement

No. 14: 140-147, 2002)

HIGH-RISK DRINKING has been a long-standing problem on U.S. college campuses.

By 1989, a survey of college and university presidents found that 67% rated

alcohol misuse to be a "moderate" or "major" problem on

their campus (Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, 1990). Recent

national surveys of college student alcohol use have confirmed that a sizable

minority of students drinks large quantities of alcohol. For example, a 1999

survey conducted by researchers at the Harvard School of Public Health found

that approximately two in five students at 4-year institutions engaged in heavy

episodic drinking during the 2 weeks prior to the survey, similar to what had

been found in both 1993 and 1997 (Wechsler et al., 2000). For men, heavy episodic

drinking was defined as having five or more drinks in a row, and for women as

having four or more drinks. About half of the heavy drinkers, or about one in

five students overall, drank at this level three or more times during the 2-week

period and account for 68% of all alcohol consumption by U.S. college students

(Wechsler et al., 1999).

The 1999 Harvard survey showed that heavy episodic

drinkers had far greater alcohol-related problems compared

with students who consumed lower amounts of alcohol. By

their own report, frequent heavy episodic drinkers were several

times more likely to do something they regret, miss a

class, fall behind in their schoolwork, forget where they

were or what they did, engage in unplanned sexual activity,

not use protection when having sex, argue with friends,

get hurt or injured, damage property and get into trouble

with campus or local police (Wechsler et al., 2000). There

is also a positive relationship between heavy episodic drinking

and driving after drinking (DeJong and Winsten, 1999).

There is also evidence that most students experience widespread problems as

a result of other students' misuse of alcohol (secondary heavy use effects),

including interrupted study and sleep; having to take care of a drunken student;

being insulted or humiliated; having a serious argument or quarrel; having property

damaged; unwanted sexual advances; being pushed, hit or assaulted; and being

a victim of sexual assault or date rape. Secondary heavy use effects are far

more common on campuses with large numbers of high-risk drinkers (Wechsler et

al., 2000).

Additional evidence makes clear that high-risk drinking has a profound effect

on college students, contributing to both academic failure and an unsafe campus.

Students who drink at high levels have poorer grades (Presley et al., 1996);

anecdotal evidence suggests that many students who drop out of colleges and

universities have alcohol- and other drug-related problems (Eigen, 1991).

Estimates are that between 50% and 80% of violence on campus is alcohol related

(Roark, 1993). In a study of women who had been victims of some type of sexual

aggression while in college, the respondents reported that 68% of their male

assailants had been drinking at the time of the attack (Frintner and Rubinson,

1993).

Progress in reducing high-risk drinking has been slow.

One positive note is an increase in the percentage of college

students who abstain from drinking. This figure stood

at 19.2% in the 1999 Harvard survey, up from 15.4% in

1993 and 18.9% in 1997 (looking at students from the subset

of schools that participated in all three surveys). On the

other hand, the 1999 Harvard survey found that 22.7% of

students were classified as frequent heavy use drinkers compared

with 19.8% in 1993 and 20.9% in 1997 (Wechsler et

al., 2000).

With relatively modest progress being made, college and

university presidents are under pressure to lower high-risk

drinking among their students. A key source of pressure

has been emerging case law regarding legal liability. Increasingly,

U.S. courts are ruling that colleges and universities

cannot ignore high-risk alcohol consumption, but

instead have an obligation to take reasonable measures to

create a safe environment by reducing foreseeable risks

(Bickel and Lake, 1999). In 1997, student deaths by alcohol

poisoning at Louisiana State University and the Massachusetts

Institute of Technology put the issue of student

drinking on the national agenda. As a result, Mothers

Against Drunk Driving (MADD), College Parents of

America, The Century Council and other groups have urged

students and their parents to demand stronger prevention

measures to ensure student safety.

Institutions of higher education have focused their prevention

efforts on educational and intervention strategies

oriented to influencing and meeting the needs of individual

students (Larimer, this supplement). Such programs are essential,

of course, but are only a part of what is necessary

to reduce alcohol-related problems on a large scale. Community-based prevention research suggests the need for a

broader effort, one that also seeks to reshape the physical,

social, economic and legal environment that affects alcohol

use (Holder et al., 1997; Perry et al., 1996). Informed by

this research, and inspired by the example of the anti-drunk

driving movement in the United States, the environmental

management approach promoted by the U.S. Department

of Education's Higher Education Center for Alcohol and

Other Drug Prevention urges campus administrators to adopt

a comprehensive approach to prevention that goes beyond

individually focused health education programs to include

strategies designed to change the campus and community

environment in which students make decisions about alcohol

use (DeJong et al., 1998).

This article first describes a social ecological framework

commonly used in public health work and its application to

the problem of college student drinking. This framework is

then expanded to create a full typology of campus-based

prevention and treatment options, which can be used by

prevention planners to provide a systematic review of current

efforts and to inform future strategic planning. Next,

the article reviews recent case studies showing the promise

of campus-based environmental management strategies. Finally,

the article reports findings from a national survey of

U.S. colleges and universities about available resources for

pursuing environmentally focused prevention. At this time,

the majority of U.S. campuses have not yet installed the

basic infrastructure required to develop, implement and

evaluate a comprehensive approach to prevention that features

environmentally focused strategies.

Environmental Management: A Social Ecological Framework

Prevention work in the public health arena has been

guided by a social ecological framework, which recognizes

that any health-related behavior, including college student

drinking, is affected through multiple levels of influence:

intrapersonal (individual) factors, interpersonal (group) processes,

institutional factors, community factors and public

policies (Stokols, 1996). On most campuses, prevention efforts

have concentrated on intrapersonal factors, interpersonal

processes and a subset of institutional factors. Less

attention has been paid to factors in the local community

that affect student alcohol use; calls by campus officials

for changes in state or federal policy remain rare.

Campus prevention activities focused on intrapersonal

or individual factors have been designed to increase student

awareness of alcohol-related problems, to change individual

attitudes and beliefs, to foster each student's

determination to avoid high-risk drinking and to intervene

to protect other students whose substance use has put them

in danger. Typical among these efforts are freshman orientation,

alcohol awareness weeks and other special events

and curriculum infusion, where faculty introduce alcohol-related

facts and issues into their regular academic courses

(Ryan and DeJong, 1998). The assumption behind these

approaches is that once students are presented with the facts

about alcohol's dangers they will make better-informed and

therefore healthier decisions about drinking. Rigorous evaluations

of these educational programs are rare, but work in

elementary and secondary school-based settings suggests

that, although these types of awareness programs are necessary,

information alone is usually insufficient to produce

behavior change (Ellickson, 1995).

Larimer's (this supplement) literature review suggests

there is little evidence that standard awareness and values

clarification programs can reduce alcohol consumption by

college students. There are new approaches being studied

that hold promise, however, including expectancy-challenge

procedures (involving alcohol/placebo administration), brief

motivational feedback interviews and alcohol skills training.

These approaches require further study to determine

the most effective combination of program components. The

ultimate challenge, however, may be in figuring out how to

bring these programs to scale so that the behavior of large

numbers of students will be affected, not just a small number

of research participants.

Activities focused on interpersonal or group processes

have been designed to use peer-to-peer communication to

change student social norms about alcohol and other drug

use. The largest such program, the BACCHUS/GAMMA

Peer Education Network, trains volunteer student leaders to

implement a variety of awareness and educational programs

and to serve as role models for other students to emulate.

Formally structured peer programs are the most common,

but some campuses have experimented with more informal

approaches. At Dartmouth College, for example, health educators

train a large cadre of students to engage other students

in dialogue when they overhear them make

pro-drinking comments. Because well-structured evaluations

of peer education are rare, such programs remain an unproven

strategy for reducing student alcohol consumption.

The value of these programs, which have limited reach compared

with other, less expensive educational strategies, might

also be questioned on cost-effectiveness grounds.

Social norms campaigns are another prevention strategy

designed to affect interpersonal processes. This approach is

grounded in the well-established observation that college

students greatly overestimate the number of their peers who

drink heavily (Perkins and Wechsler, 1996). Because this

misperception drives normative expectations about alcohol

use, which in turn influence actual use, a viable prevention

strategy is to correct the misperception (Perkins and

Berkowitz, 1986). A social norms campaign attempts to do

this by using campus-based mass media (e.g., newspaper

advertisements, posters, email messages) to provide more

accurate information about actual levels of alcohol use on

campus. Preliminary studies at Northern Illinois University

and other institutions suggest that this approach to changing

the social environment has great promise as a prevention

strategy (Perkins, this supplement), but more definitive

research is still needed to gauge its real impact in reducing

student alcohol consumption.

A broader focus on institutional factors, community factors

and public policy constitutes the doctrine of environmental

management articulated by the Higher Education

Center for Alcohol and Other Drug Prevention. The need

for environmental change is evident when one considers

the types of mixed messages about high-risk alcohol consumption

that are abundant in college communities. In the

community, for example, many liquor stores, bars and Greek

houses fail to check for proof-of-age identification. Local

bars and restaurants offer happy hours and other low-price

promotions or serve intoxicated patrons. Where it is allowed,

on-campus advertising for beer and other alcoholic

beverages "normalizes" alcohol consumption as an inherent

part of student life, and an absence of alcohol-free social

and recreational options makes high-risk drinking the

default option for students seeking spontaneous entertainment.

Of critical importance, lax enforcement of campus

regulations, local ordinances or state and federal laws

teaches students to disregard the law. Until these mixed

messages in the campus and community are changed, college

officials face an uphill battle in reducing high-risk alcohol

consumption and the harm it can cause.

Following the social ecological framework, there are

three spheres of action in which environmental change strategies

can operate: the institution of higher education, the

surrounding community and state and federal laws and regulations.

Key to developing and implementing new policies

in all three spheres is a participatory process that includes

all major sectors of the campus and community, including

students.

On campus, an alcohol and other drug task force should

conduct a broad-based examination of the college environment,

looking not only at alcohol and other drug-related

policies and programs, but also the academic program, the

academic calendar and the entire college infrastructure. The

objective is to identify ways in which the environment can

be changed to clarify the college's expectations for its students,

better integrate students into the intellectual life of

the college, change student norms away from alcohol and

other drug misuse or make it easier to identify students in

trouble with substance use.

Work in the surrounding community can be accomplished through a campus and

community coalition. Community mobilization, involving a coalition of civic,

religious and governmental officials, is widely recognized as a key to the successful

prevention of alcohol- and other drug-related problems (Hingson and Howland,

this supplement). Higher education officials, especially college and university

presidents, can take the lead in forming these coalitions and moving them toward

an environmental approach to prevention (Presidents Leadership Group, 1997).

A chief focus of a campus-community coalition should be to curtail youth access

to alcohol and to eliminate irresponsible alcohol sales and marketing practices

by local bars, restaurants and liquor outlets.

College officials should also work for policy change at both the state and

federal levels. New laws and regulations will affect the community as a whole

and can help perpetuate changes in social norms, thereby affecting student alcohol

use. There are several potentially helpful laws and regulations that can be

considered, including distinctive and tamper-proof licenses for drivers under

age 21, increased penalties for illegal service to minors, prohibition of happy

hours and other reduced-price alcohol promotions, restricted hours of sales,

reduced density of retail outlets and increased excise tax rates on alcohol

(Toomey and Wagenaar, 1999). A state-level association of colleges and universities

can provide the organizational mechanism for college presidents and other top

administrators to speak out on these and other issues, while also providing

a structure for promoting the simultaneous development of several campus and

community coalitions within a state.

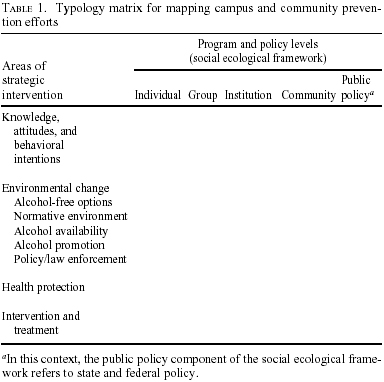

A Typology of Campus and Community Interventions

The Higher Education Center's environmental management

framework encourages college presidents and other

top administrators to reconceptualize their prevention work

to include a comprehensive restructuring of the campus and

community environment (DeJong et al., 1998). Recently,

the Center has expanded this framework to create a full

typology of campus-based prevention and treatment options.

This typology can be used to categorize existing efforts,

identify missing program elements and guide new strategic

planning.

The social ecological framework defines one dimension

of the typology, with programs and policies classified into

one of five levels: individual, group, institution, community

and state and federal public policy. The second dimension

of the Center's typology concerns the key areas of

strategic intervention, each of which is linked to a particular

definition of the problem of alcohol use in colleges.

There are four alternatives to be considered: (1) changing

people's knowledge, attitudes and behavioral intentions regarding

alcohol consumption; (2) eliminating or modifying

environmental factors that contribute to the problem; (3)

protecting students from the short-term consequences of alcohol

consumption ("health protection" or "harm reduction"

strategies); and (4) intervening with and treating students

who are addicted to alcohol or otherwise show evidence of

problem drinking.

These two dimensions can be represented as a matrix,

as in Table 1. This representation captures the idea that

many areas of strategic intervention can be pursued at one

or several levels: individual, group, institution, community

and state and federal public policy. For example, in the

realm of health protection, a local community could decide

to establish a "safe rides" program. This community-level

program would be strengthened by the addition of complementary

efforts at other levels of the social ecological model.

For example, at the group level, fraternity and sorority chapters

could vote to require members to sign a pledge not to

drink and drive and instead to use the safe rides program.

Operating at the individual level, there could be a campusbased

media campaign that encourages individual students

to utilize the new service.

Consider another example focused on increased observance and enforcement of

the minimum drinking age law. At the state level, the alcohol control commission

could increase the number of decoy (or "sting") operations at local

bars and restaurants. At the community level, local police could implement a

protocol for notifying college officials of all alcohol-related incidents involving

students. At the institution itself, the campus pub could require that all alcohol

servers complete a training course in responsible beverage service. At the group

level, the college might require that residential groups and special event planners

provide adequate controls to prevent alcohol service to underage students. Finally,

at the individual level, a media campaign could publicize these new policies,

the stepped-up enforcement efforts and the consequences of violating the law.

Implementing multiple strategies in support of a single strategic objective

will increase the likelihood of that objective being achieved.

The typology divides the environmental change category

into five subcategories of strategic interventions: (1) offer

and promote social, recreational, extracurricular and public

service options that do not include alcohol; (2) create a

social, academic and residential environment that supports

health-promoting norms; (3) limit alcohol availability both

on- and off-campus; (4) restrict marketing and promotion

of alcoholic beverages both on- and off-campus; and (5)

develop and enforce campus policies and local, state and

federal laws. Each of these subcategories involves a wide

range of possible strategic objectives, as shown in Table 2.

One use of the typology matrix is for campus-community coalitions to categorize

their current programs and policies. In practice, most coalitions find that

the bulk of their efforts are focused on addressing knowledge, attitudes and

behavioral intentions regarding alcohol consumption, which is most often attempted

through programs designed to reach students as individuals. What environmental

change strategies there are tend to be focused at the institutional level. Once

gaps are noted, the coalition can use the matrix to explore systematically how

to expand or modify their programs and policies. Training and technical assistance

services provided by the Higher Education Center for Alcohol and Other Drug

Prevention are designed to encourage a detailed exploration of the five subcategories

of environmentally focused strategic interventions.

The typology's matrix structure also leads to a consideration

of how a program or policy that operates at one level

of strategic intervention (as defined by the social ecological

framework) might be complemented by efforts operating

at other levels. For example, a social norms campaign,

which operates primarily at the group level, could be enhanced

by an alcohol screening program that gives individualized

feedback to students on their drinking compared

with other students on campus (Marlatt et al., 1998). As

another example, community leaders might foster the creation

of new businesses that can provide recreational options for students. Simultaneously,

college officials might

create a center to promote student involvement in service

learning projects, while also conducting an awareness campaign

to inform students of the career advantages of community

volunteer work. The idea is to design programs and

policies that work in sync to change the campus and community

environment, thereby offering a safer and richer

learning experience for students.

Emerging Evidence on Environmental Management Strategies

Very few college-focused alcohol prevention programs

have undertaken an evaluation that meets even minimal

scientific standards. As a result, to guide future program

and policy development, the Higher Education Center for

Alcohol and Other Drug Prevention relies on the broader

prevention literature, which clearly points to the potential

for coalition-driven environmental change strategies

(Hingson and Howland, this supplement). The Center's

training program for campus and community coalitions,

technical assistance services and publications have urged

college officials to adopt this broader approach, based on

the reasoned expectation that what has been shown to work

to reduce alcohol-related problems in the population at large

will also work to reduce alcohol-related problems among

college students.

Recent case study reports underscore the potential value

of an environmental approach to reduce alcohol-related

problems among college students. In Albany, New York,

for example, a campus-community coalition worked to reduce

problems related to off-campus student drinking. Committee

initiatives included improving enforcement of local

laws and ordinances, sending safety awareness mailings to

off-campus students and developing a comprehensive advertising

and beverage service agreement with local tavern

owners. These initiatives were associated with a decline in

the number of alcohol-related problems in the community,

as indicated by decreases in the number of off-campus noise

ordinance reports filed by police and in the number of calls

to a university-maintained hotline for reporting off-campus

problems (Gebhardt et al., 2000).

In 1995, the University of Arizona installed and publicized

new policies to provide better alcohol control during

its annual homecoming event. Systematic observation at

pregame tents showed that, compared with 1994, these policies

led to a lower percentage of tents selling alcohol, elimination

of beer kegs, greater availability of food and

nonalcoholic beverages, the presence of hired bartenders to

serve alcohol and systems for ID checks. These changes

were still in evidence through 1998. In 1995, campus police

also saw a downward shift in the number of neighborhood

calls for complaints related to homecoming activities,

which was maintained through 1998. Statistics on law enforcement

actions were inconsistent. There was a sharp drop

in 1995, but 1996 and 1998 saw enforcement levels similar

to what was seen before the new policies (Johannessen et

al., 2001).

Researchers at the University of Rhode Island conducted

a study to assess the impact of the university's tougher

alcohol policies, which were installed in 1991, including

prohibitions against underage drinking or alcohol possession,

public alcohol consumption and use of kegs or other

common alcohol containers. The results suggested that aggressive

enforcement of the new policies led to a 60% decrease

in more serious alcohol violations (Cohen and

Rogers, 1997).

Additional scientifically based research is needed to assess

the effectiveness of college-based prevention programs

that feature environmentally focused policies and programs.

Why have there been so few good program and policy

evaluations? In general, the problem is not that program

directors are unaware of the need for evaluation, or that

they are worried about their program failing to measure up.

Rather, it is that, until recently, most foundations and government

agencies invested insufficient resources in evaluation

research. Good research in this area is expensive. On a

promising note, new research initiatives funded by the U.S.

Department of Education, the National Institute on Alcohol

Abuse and Alcoholism and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

should soon make it possible for a scientifically based

research literature to emerge.

With the promise of environmental management strategies

for reducing alcohol-related problems among college

students, the question arises as to how many colleges and

universities have the resources needed to pursue this approach.

Reported next are the results of a national study

conducted by the Higher Education Center for Alcohol and

Other Drug Prevention to answer that question.

National Survey of Senior Campus Administrators

In 1998, the Higher Education Center conducted its first

Survey of American College Campuses to learn more about

the types of alcohol and other drug prevention efforts now

in place in U.S. institutions of higher education. Of particular

interest was the extent to which colleges and universities

have installed the infrastructure they need to

develop, implement and evaluate a comprehensive program

that includes prevention strategies with an environmental

management focus.

The study sample was an equal probability sample of 365 two- and four-year

colleges and universities, both public and private, drawn from an updated database

of U.S. institutions of higher education. All of the selected institutions had

undergraduate students and granted an associates degree or higher. A survey

was mailed to the senior administrator responsible for coordinating each school's

institutional response to alcohol- and other drug-related problems.

One survey was returned without a forwarding address

for the institution, leaving a total sample size of 364. With

280 completed surveys, the response rate was 76.9%. Of

those providing this information, 133 were from a 4-year

institution (48.0%) and 144 were from a 2-year school

(52.0%).

Current funding and staff levels

Fully 81.1% of the respondents reported that "hard

money" (nongrant) funding for their institution's alcohol

and other drug prevention programs had remained the same

during the past 3 years; 9.4% reported that funding had

increased, and 9.4% reported that funding had decreased.

Results for 4- and 2-year institutions were somewhat different.

Roughly equal percentages of respondents said that

funding had decreased (4-year schools, 9.2%; 2-year

schools, 9.7%); more 4-year schools (16.8%) than 2-year

schools (1.8%) had funding increases during the past 3

years.

On average, respondents to the Center's survey stated

that 1.2 full-time equivalent (FTE) staff were employed at

their institution to develop and implement alcohol and other

drug prevention programs and policies. Four-year institutions

reported having more staff devoted to this work than

did 2-year schools: less than one FTE (4-year schools,

38.5%; 2-year schools, 57.8%), one to less than two FTEs

(4-year schools, 40.4%; 2-year schools, 24.8%) and two or

more FTEs (4-year schools, 21.1%; 2-year schools, 17.4%).

Prevention infrastructure

Respondents to the survey were also asked questions

about their school's infrastructure for developing prevention

programs and policies. Only 39.8% of the respondents

reported that their institution had a campus-wide task force

or committee in place to oversee prevention efforts. Among

those with a task force, 70.1% reported participation by the

president or the president's designee. Respondents from 4-year schools were far more likely than those from 2-year

schools have a campus-wide task force (51.5% vs 29.6%,

respectively).

Only 28.5% of the respondents said that their institution was part of a local

coalition focused on alcohol and other drug prevention. Again, there was a large

difference between 4- and 2-year institutions. Fully 37.9% of respondents from

4-year schools said that they participated in such a coalition compared with

18.9% of those from 2-year schools. In addition, 32.6% of the respondents reported

that their institution was part of a state-level association focused on prevention.

This was the case for 41.3% of 4-year institutions but only 23.3% of 2-year

schools.

Data collection and research

Only 19.8% of the respondents reported that their institution conducts a formal

assessment of the implementation and impact of its alcohol and other drug policies

and programs. This was the case for 25.2% of 4-year schools and 13.9% of 2-year

schools.

Only 37.3% of the respondents said that their institution

carries out a formal survey of student alcohol and other

drug use, knowledge and attitudes. Again, there were large

differences between 4- and 2-year institutions. Such a survey

was conducted at 58.3% of 4-year institutions and only

17.7% of 2-year schools.

Two-thirds of the respondents (66.3%) indicated that their

institution's prevention effort includes a review of incident

reports from campus security. This was the case for 72.1%

of 4-year schools and 62.2% of 2-year schools. Only 35.4%

of institutions review summary statistics from student health

services; this was done at 48.4% of 4-year schools but only

23.1% of 2-year schools.

Conclusions

To prevent alcohol- and other drug-related problems on campus, college

and university administrators are being asked to adopt a more comprehensive

prevention approach that features environmentally focused strategies. Because

this represents a profound shift in how most college and university administrators

think about alcohol and other drug prevention, this change in approach will

come slowly, a fact reinforced by the results of the 1998 Survey of American

College Campuses.

Cultivating and sustaining a campus and community environment

in which students are helped to make healthier

decisions about substance use requires a long-term financial

investment. The Higher Education Center's new typology

of campus and community prevention efforts makes

clear there is much more involved here than tougher campus

policies and stricter enforcement. However, despite recent

publicity about college student drinking, approximately

9 in 10 U.S. colleges and universities did not increase their

nongrant budget allocation for alcohol and other drug prevention

during the 3 years previous to the 1998 Survey of

American College Campuses.

In addition, the vast majority of colleges and universities

have not yet put in place the basic infrastructure they

need to develop, implement or evaluate this comprehensive

approach. Progress will be greatly facilitated by constituting

a permanent campus task force that reports directly to

the president, participating actively in a campus-community

coalition that seeks to change the availability of alcohol

in the local community and joining a state-level

association that speaks out on state and federal policy

issues.

Another important role of state-level associations is to

facilitate the simultaneous development of multiple campus

and community coalitions within a state (Deucher et

al., in press). The advantages of this approach to infrastructure

development are several. First, having several institutions

join together in common effort makes clear that

high-risk drinking is not a problem of any one campus, but

one that all colleges and universities share in common. Second,

a state-level effort will draw media attention, which

can be used to reinforce the fact that high-risk drinking is

not the social norm on campus and to build the case for

environmentally focused solutions. Third, a statewide initiative

can attract additional funds for prevention. In various

states, funds for a state initiative have been provided

by departments of state government, the state alcohol beverage

control commission and private foundations.

As noted previously, as colleges and universities continue

to experiment with a broader range of environmental

strategies, additional research is needed to assess their effectiveness

and to build a true science of campus-based

prevention. Clearly, an environmental approach to drunk

driving prevention has led to great reductions in alcohol-related

traffic fatalities in the United States (DeJong and

Hingson, 1998). Indeed, it was the success of the anti-drunk

driving movement that informed the Higher Education

Center's doctrine of environmental management. Ultimately,

however, if college and university officials are to continue

making the investment that an environmental approach requires,

evidence is needed about which strategies work best

under particular circumstances and are the most cost

effective.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge comments provided on two earlier

drafts of this article by David Anderson, Ph.D., George Mason University,

and Alan Marlatt, Ph.D., University of Washington.

References

Bickel, R.D. and Lake, P.F. The Rights and Responsibilities of the Modern

University: Who Assumes the Risks of College Life, Durham,

NC: Carolina Academic Press, 1999.

Carnegie Foundation for The Advancement of Teaching. Campus Life:

In Search of Community, Princeton, NJ: Carnegie Foundation for the

Advancement of Teaching, 1990.

Cohen, F. and Rogers, D. Effects of alcohol policy change. J. Alcohol Drug

Educ. 42 (2): 69-82, 1997.

DeJong, W. and Hingson, R. Strategies to reduce driving under the influence

of alcohol. Annual Rev. Publ. Hlth 19: 359-378, 1998.

DeJong, W., Vince-Whitman, C., Colthurst, T., Cretella, M., Gilbreath,

M., Rosati, M. and Zweig, K.

Environmental Management: A Comprehensive

Strategy for Reducing Alcohol and Other Drug Use on

College Campuses, Newton, MA: Higher Education Center for Alcohol

and Other Drug Prevention, Department of Education, 1998.

DeJong, W. and Winsten, J.A. The use of designated drivers by U.S. college

students: A national study. J. Amer. Coll. Hlth 47: 151-156, 1999.

Deucher, R.M., Block, C., Harmon, P.N., Swisher, R., Peters, C. And

DeJong, W.

A statewide initiative to prevent high-risk drinking on

Ohio campuses: An environmental management case study. J. Amer.

Coll. Hlth, in press.

Eigen, L.D. Alcohol Practices, Policies, and Potentials of American Colleges

and Universities: An OSAP White Paper, Rockville, MD: Office

for Substance Abuse Prevention, 1991.

Ellickson, P.L. Schools. In: Coombs, R.H. and Ziedonis, D. (Eds.) Handbook

on Drug Abuse Prevention: A Comprehensive Strategy to Prevent the Abuse of Alcohol

and Other Drugs, Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon, 1995, pp. 93-120.

Frintner, M.P. and Rubinson, L. Acquaintance rape: The influence of alcohol,

fraternity membership, and sports team membership. J. Sex Educ. Ther. 19:

272-284, 1993.

Gebhardt, T.L., Kaphingst, K. and DeJong, W. A campus-community coalition to

control alcohol-related problems off campus: An environmental management case

study. J. Amer. Coll. Hlth 48: 211-215, 2000.

Holder, H.D., Saltz, R.F., Grube, J.W., Treno, A.J., Reynolds, R.I., Voas,

R.B. and Gruenewald, P.J. Summing up: Lessons from a comprehensive community

prevention trial. Addiction 92 (Suppl. No. 2): S293-S301, 1997.

Johannessen, K., Glider, P., Collins, C., Hueston, H. and DeJong, W. Preventing

alcohol-related problems at the University of Arizona's homecoming: An environmental

management case study. Amer. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 27: 587-597, 2001.

Marlatt, G.A., Baer, J.S., Kivlahan, D.R., Dimeff, L.A., Larimer, M.E., Quigley,

L.A., Somers, J.M. and Williams, E. Screening and brief intervention for high-risk

college student drinkers: Results from a twoyear follow-up assessment. J. Cons.

Clin. Psychol. 66: 604-615, 1998.

Perkins, H.W. and Berkowitz, A.D. Perceiving the community norms of alcohol

use among students: Some research implications for campus alcohol education

programming. Int. J. Addict. 21: 961-976, 1986.

Perkins, H.W. and Wechsler, H. Variation in perceived college drinking norms

and its impact on alcohol abuse: A nationwide study. J. Drug Issues 26:

961-974, 1996.

Perry, C.L., Williams, C.L., Veblen-Mortenson, S., Toomey, T.L., K omro, K.A.,

Anstine, P.S., McGovern, P.G., Finnegan, J.R., Forster, J.L., Wagenaar, A.C.

and Wolfson, M. Project Northland: Outcomes of a communitywide alcohol use prevention

program during early adolescence. Amer. J. Publ. Hlth 86: 956-965, 1996.

Presidents Leadership Group. Be Vocal, Be Visible, Be Visionary: Recommendations

for College and University Presidents on Alcohol and

Other Drug Prevention, Newton, MA: Higher Education Center for

Alcohol and Other Drug Prevention, Department of Education, 1997.

Presley, C.A., Meilman, P.W. and Cashin, J.R. Alcohol and Drugs on

American College Campuses: Use, Consequences, and Perceptions of

the Campus Environment, Volume IV: 1992-94, Carbondale, IL: Core

Institute, Southern Illinois University, 1996.

Roark, M.L. Conceptualizing campus violence: Definitions, underlying factors,

and effects. J. Coll. Student Psychother. 8: 1-27, 1993.

Ryan, B. and DeJong, W. Making the Link: Academics and Prevention,

Newton, MA: Higher Education Center for Alcohol and Other Drug

Prevention, Department of Education, 1998.

Stokols, D. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community

health promotion. Amer. J. Hlth Prom. 10: 282-298, 1996.

Toomey, T.L. and Wagenaar, A.C. Policy options for prevention: The case of

alcohol. J. Publ. Hlth Policy 20: 192-213, 1999.

Wechsler, H., Lee, J.E., Kuo, M. and Lee, H. College binge drinking in the

1990s: A continuing problem. Results of the Harvard School of Public Health

1999 College Alcohol Study. J. Amer. Coll. Hlth 48: 199-210, 2000.

Wechsler, H., Molnar, B.E., Davenport, A.E. and Baer, J.S. College alcohol

use: A full or empty glass? J. Amer. Coll. Hlth 47: 247-252, 1999.

*Work on this article was supported by U.S. Department

of Education contract ED-99-CO-0094 to Education Development Center, Inc., in

Newton, MA, for operation of the Higher Education Center for Alcohol and Other

Drug Prevention, for which the first author serves as director. The views expressed

here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position

of the Department of Education.

†William DeJong may be reached at the above address

or via email at: wdejong@bu.edu. Linda M. Langford is with Education Development

Center, Newton, MA.

Last reviewed: 9/23/2005

|