My Big Fat Planet: In Essence: Science Boiled Down

Thursday, January 10th, 2013

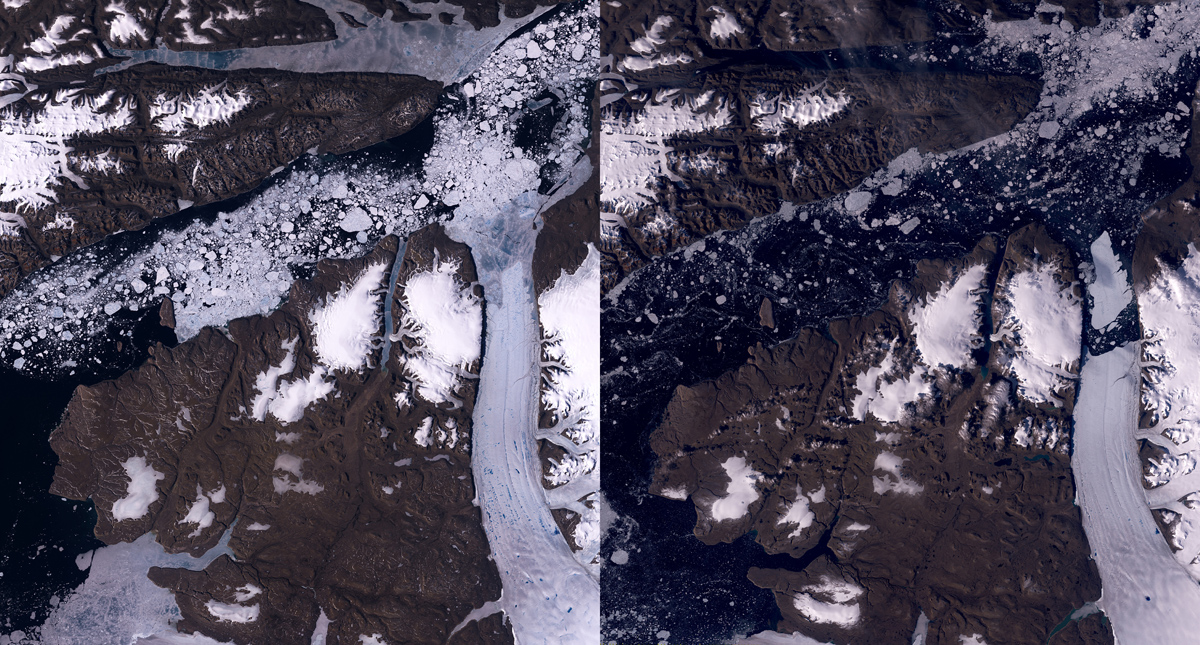

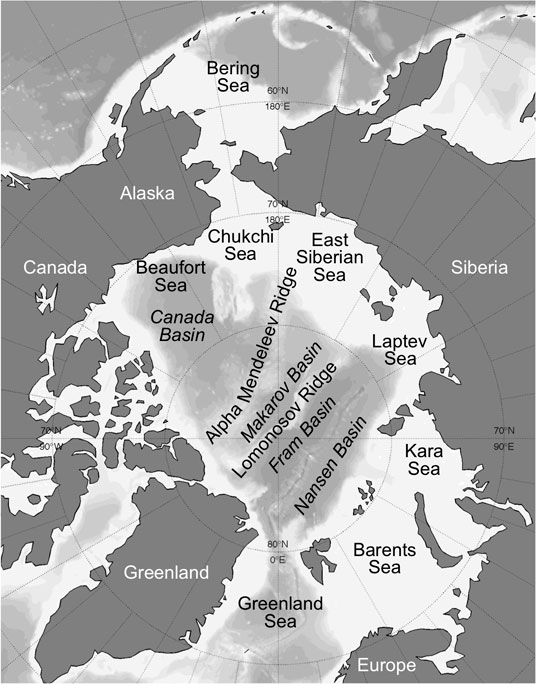

An interesting recent paper from Dr. Son Nghiem at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and colleagues finds that the bottom of the Arctic Ocean controls the pattern of sea ice thousands of feet above on the water’s surface. The seafloor topography exerts its control not only locally, in the Bering, Chukchi, Beaufort, Barents and Greenland Seas, but also spanning hundreds to thousands of miles across the Arctic Ocean.

How? The seafloor influences the distribution of cold and warm waters in the Arctic Ocean where sea ice can preferentially grow or melt. Geological features on the ocean bottom also guide how the sea ice moves, along with influence from surface winds.

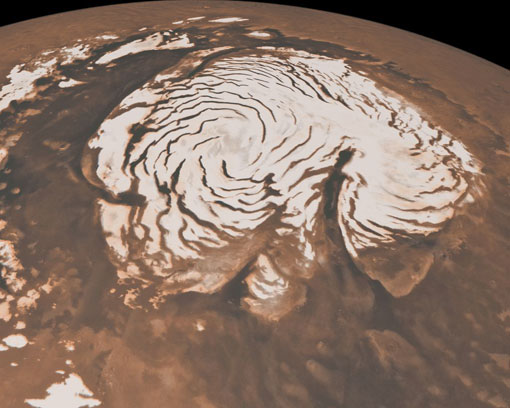

Interestingly, the study also links the bottom of the Arctic Ocean with cloud patterns up in the sky. The ocean bottom affects sea ice cover, which affects the amount of vapor coming from the surface of the ocean out into the air, which in turn influences cloud cover.

The researchers, who also come from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, the Applied Physics Laboratory and the National/Naval Ice Center in the U.S., use sea ice maps taken from space with NASA’s QuickSCAT satellite, as well as measurements from drifting buoys in the Arctic Ocean. They compare the sea ice and seafloor topography patterns to identify the connection between the two.

Bottom line:

Since the seafloor does not change significantly over many years, sea ice patterns can form repeatedly and persist around certain underwater geological features. So computer models need to incorporate these features in order to improve their forecasts of how ice cover will change over the short- and long-term. This ‘memory’ of the underwater topography could help refine our predictions of what will happen to ice in the Arctic as the climate changes.

Source:

“Seafloor Control on Sea Ice,” S. V. Nghiem, P. Clemente-Colon, I.G. Rigor, D.K. Hall & G. Neumann, Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, Volumes 77-80, pp 52-61 (2012).

This post was written for “My Big Fat Planet,” a blog hosted by Amber Jenkins on NASA’s Global Climate Change site.