Shields Up!

Save the satellites!

In "Shields Up!," the GOES-R satellite warns that bad space weather is on the way. Your job is to shield all the other Earth satellites from damage. Click here to play!

The story of a strange and (solar) stormy night . . .

This aurora appeared November 5, 2001, over Marstown Solar-powered Observatory in New Windsor, Maryland.

It is a sticky August night in Florida. Typical, except for one thing. Bright red and green curtains of light dance in the sky. Is the swamp on fire?

No. The Aurora Borealis, or Northern Lights, are lighting up the sky. It is 1859, and few people in Florida have ever seen an aurora. They are amazed and frightened.

A few days later, on September 1, English astronomer Richard C. Carrington is studying a group of sunspots (through dark filters that protect his eyes, of course). Around 11:00 AM, he sees a sudden flash of intense white light from the area of the sunspots. Seventeen hours later, the night sky in North America and as far south as Panama in Central America lights up like daytime. It is another wave of even brighter Auroras. People read newspapers by the light. Gold miners in the Rocky Mountains wake up and make coffee, bacon and eggs at 1:00 AM, thinking the Sun has risen on a cloudy morning.

Drawing by Carrington of the sunspot where the solar flare originated.

But stranger things than these are happening.

Instruments that measure changes in Earth's magnetism are acting crazy, their needles stuck against the pins at the highest end of the scale. Spikes of electricity surge into the world's telegraph systems, and no one can send a message.

What is going on?

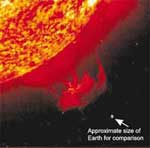

In 1859, even scientists didn't understand what caused auroras and the electrical and magnetic disturbances that went with them. Eventually they figured out that auroras are caused by violent events on the Sun. These solar storms can blast out huge clouds of electrified gas and dust at up to 2 million miles per hour. If this high-energy blast of particles reaches Earth, it can temporarily distort and disrupt Earth's magnetic field.