Friday, February 1, 2013. The following is a guest post provided by Peter Sheppard Skærved, who recently appeared at the Library in events dedicated to its Paganini holdings and collection of Cremonese instruments.

I am powerfully aware of the constant dialogue between past and present. Working as a violinist equally involved with the discovery of music old and new, this is perhaps inevitable, as every day I am in conversation with my collaborating composers. It makes very little difference to me whether they are alive or dead—they still nag me in the middle of the night! The great American master George Rochberg is one of these. I was lucky enough to meet him in 1999, and it is largely because of him that I started to take Paganini seriously. Working on his epochal Caprice Variations, alongside his quartets and the reconstruction of his tremendous Violin Concerto, which I premiered and recorded in 2002, gave me ample demonstration of how George saw Paganini as a conduit through which much of performance and composition before and since needs must pass. George used to ring me at 2 or 3 in the morning to check that I was still working. He died in 2005, and is still ringing me up—the relationship hasn’t changed, although the burden of responsibility has.

In many ways this sums up how the “flow” between past and present works for a classical artist. Working with a living composer of any generation, being part of the creative and collaborative process, observing the subtle shifts in hierarchy and artistic “ownership”—this constantly informs my engagement with the music of past composers like Beethoven, Tartini, Berg and others. My “Paganini Project” at the Library of Congress is rooted in the richness of the objects and texts which an institution like this can offer. However, light is shone on those “dry bones” by what we do now. And the input of living composers into this process constantly offers me different ways to understand how to answer the question: “Shall these dry bones live?”

The Library contains some inspiring objects of “Paganiniana” that, as I have spent time with them, and thinking about them, enliven my work as performer. An example: The Library possesses a memo from the Minister of Public Works in Paris (the Comte d’Argout) concerning Paganini’s concert “from which the profit will be destined to alleviate the sufferings which could arise from the Cholera.” Paganini himself noted on the 18th of April, 1832: “Next Thursday I will give a concert at the Gran Teatro for the benefit of the sick. Rossini has fled from fear; on the other hand, I have had no desire at any time to be anything but useful for humanity.” Paganini composed a Fantasia for this benefit concert that is lost, but talking about it with composer Judith Bingham inspired her Cholera Fantasia, one of her Lost Works of Paganini (see below).

There are a large number of composers who are involved with my Paganini explorations. The works they are producing are autonomous, but each of them has found different ways to reflect upon Paganini in order to find material, Stoff, to cut and sew into their own forms. In turn, my involvement in this process shines a light for me onto the historical artifacts and questions. Four composers have been particularly involved with the Paganini Project: Judith Bingham, David Gorton, David Matthews (all from the U.K.) and Paul Osterfield, whom I met at Middle Tennessee State University in 2011.

Paul Osterfield is the composer who offered the most concentrated response to my Paganini investigations. In the summer of 2011, he succeeded in writing me 24 caprices in a month. Although we were both in the U.S.A. at the time, we were unable to be together; he was in Murfreesboro, and I was staying at my father-in-law’s (Garrison Keillor) house in St. Paul. So we worked online. Each day he wrote a new caprice, which I would open up in the morning and record in Garrison’s beautiful music room between 7 and 9am. Osterfield’s 16th Caprice explores the more delicate effects that are possible with Paganini’s use of double harmonics. While I was practising, Garrison drifted into the room—“What is that? Such ethereal music?” He was right; this is the music of the spheres. Or, as Ungaretti put it:

a una

a una

si svelano

le stelle

[one by one the stars are revealed]

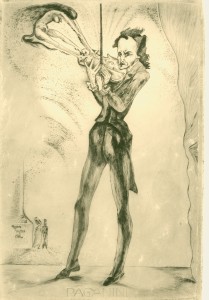

David Matthews is one of the great living British composers, and celebrates his 70th birthday this year. For a non-string player, he has written a huge amount of violin music (in addition to his magisterial 12 String Quartets). This body of work includes a set of 15 Fugues for solo violin. He wrote his Paganini Fantasia for me as a terrifying re-imagining of what Paganini might do today. Recently he wrote to me about my performance of this work on Il Cannone, Paganini’s great Guarnerius del Gesu violin, to which he gave the nickname “The Cannon” on account of its power (it was given to him after he lost his own violin gambling in Livorno in 1803). It is the treasured cultural artifact of the City of Genoa, a grail for makers and players, and very few of us have been permitted to play it. David sums up its unique power: “The sound is like no violin I’ve ever heard, it has a special intensity; and listening to my Fantasia, whose cadenza I tried to write as if it was by Paganini himself, I could easily imagine I was hearing Paganini’s own playing. I liked the way you played the first part, Peter, with your back to the audience and then turned round dramatically for the cadenza—a theatrical gesture Paganini would surely have appreciated.” It seems that Paganini began using theatrical effects in his concerts in Paris in 1831. The orchestra remained in the “pit,” and for the opening tutti of his concerti, the audience would be presented with little more than a black draped stage. Then, with a drum roll, Paganini would appear, his naturally cadaverous aspect and black clothes emphasizing his popular association with the occult. A caricature in the Library of Congress collection contains the following account of the effect that this had: “…an involuntary cheering burst from every part of the house, many rising from their seats to view the spectre as he glided from the side scenes to the front of the stage, his gaunt and extraordinary appearance being more like that of a devotee [about] to suffer martyrdom than one to delight you with his art…”

Judith Bingham has a special rapport with the early 19th-century through her empathy for literature. She endeared herself to me with a wonderful set of miniatures based on the life of Percy Bysshe Shelley, and was a terrific help for me in understanding Paganini’s psychological makeup. Together, we became fascinated by the “missing works,” the opere perdute in the Catalogo tematico published by the city of Genoa. Gradually this fascination and our long, wandering conversations over coffee revealed themselves as a cycle—The Lost Works of Paganini. These include a re-imagination of Paganini’s Scena Amorosa, which Paganini wrote for Napoleon Bonaparte’s sister, Elisa, when he was in her service at the ducal court in Lucca.

David Gorton is fascinated with virtuosity, and is one of the composers who like to (figuratively) push me off the cliff and see what happens. His Caprices is a set which has grown gradually since 2006, when he wrote the first Rosetta Caprice, which challenged me to match my ricochet and staccato speeds in the way that it seemed Paganini could do. Since then his caprices have explored the tactile cliff edge of sound and silence, movement and stillness. The most recent of them was designed for me to play walking around the exhibition that I curated for the National Portrait Gallery in London, Only Connect. It consists of chords stolen from the composers in the exhibit, including of course, Paganini himself, who finds himself in a dialogue of which Rochberg would approve, with composers such as Delius, Joseph Joachim (whose violin I normally play), Priaulx Rainier, and Stravinsky, who allowed a Paganini-esque Devil to make merry hell for the violinist in L’Histoire du Soldat.

And whilst all this exploration of the now goes on with the “Paganini Project,” the delving into the past gets more and more exciting. The work stretches from the past to the present, a stretch that is encouraged by the wonderful team at the Library. So we are discussing the light that can be shed on Paganini’s sound by using gut strings and transitional bows with the Cremonese instruments that he championed. Meanwhile, the insights offered by Paganini’s Red Book have inspired research events at the Royal Academy of Music and a concert at the prestigious Bergen Festival in Norway, all constantly enlivened by the creative ears and eyes of the living composers who, following the lead of George Rochberg, continue to inspire this work.