Current Challenges and Best Practices for ERISA Compliance for 403(b) Plan Sponsors

This report was produced by the Advisory Council on Employee Welfare and Pension Benefit Plans, usually referred to as the ERISA Advisory Council (the “Council”). The Council was established under Section 513 of ERISA to advise the Secretary of Labor. This report examines current challenges and best practices(1) for ERISA compliance for 403(b) plan sponsors. The contents of this report do not represent the position of the Department of Labor (DOL).

|

November 9, 2011

Dear Secretary Solis:

The 2011 Advisory Council on Employee Welfare and Pension Benefit Plans is pleased to present its Report on Current Challenges and Best Practices for ERISA Compliance for 403(b) Plan Sponsors.

The Council has a diverse membership drawing from both profit and non-profit entities and representing various stakeholders in the provision of employee benefits to American workers and their families. We have a shared commitment to improving the provision of those benefits. This has enabled us to reach a consensus on a number of matters relevant to the issues we have examined.

The attached report was prepared after two days of testimony by 13 witnesses followed by discussion and deliberation by the Council.

We wish to gratefully acknowledge the assistance of all persons listed under “Acknowledgements” and, in particular, Larry Good and DiWeena Streater of the Employee Benefits Security Administration. Respectfully submitted,

/s/

Theda R. Haber, Council Chair

Mildeen Worrell, Council Vice Chair

Marilee P. Lau, Issue Chair

Richard A. Turner, Issue Vice Chair

Theresa Atanasio, Drafting Team Member

Karin S. Feldman, Drafting Team Member

J.M. Towarnicky, Drafting Team Member

Karen Kay Barnes

Sewin Chan

Denise M. Clark

Anna M. Rappaport

Michael Sasso

Mary Ellen Signorille

Michael F. Tomasek

Gary A. Thayer

Abstract

The 2011 ERISA Advisory Council studied the Current Challenges for ERISA Compliance for 403(b) Plan Sponsors and heard testimony supporting the proposition that there is a need for additional clarification and guidance for plan sponsors who maintain and/or offer 403(b) plans. The objectives of this report are to (1) identify areas where guidance is confusing or lacking relating to complying with the new 403(b) regulations and (2) to determine what actions the Department of Labor (DOL) could take to enhance compliance with the regulations issued by DOL, as well as to ease certain regulatory burdens for 403(b) plan sponsors, especially smaller employers.

Acknowledgements

The Council recognizes the following individuals and organizations who contributed greatly to the Council’s deliberations and final report.

Larry Good, Employee Benefit Security Administration (EBSA)

DiWeena Streater, EBSA

July 21, 2011

Bob Architect, The Variable Annuity Life Insurance Company (VALIC)

James Szostek, American Council of Life Insurers (ACLI)

Richard Skillman, Caplin & Drysdale, Chartered

M. Kristi Cook, National Tax Sheltered Accounts Association (NTSAA) & American Society of Pension Professionals and Actuaries (ASPPA)

Joe Canary, EBSA

Ian Dingwall, EBSA

Susan Diehl, PenServ Plan Services

Bob Lavenberg, American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA)

August 30, 2011

William Bortz, The U.S. Department of the Treasury (Treasury)

Sherri Edelman, Internal Revenue Service (IRS)

Elena Chism, Investment Company Institute (ICI)

Weiyen Jonas, FMR LLC (FMR)

David John, Retirement Made Simpler–A coalition formed by AARP, FINRA & RSP

Prince Group (letter submitted to the Council and contained in the record)

2010 and 2011 403(b) Plan Surveys provided by Plan Sponsor Council of America (PSCA)

Executive Summary

Retirement plans established for public schools and certain tax-exempt organizations in accordance with section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code (the “Code”) are commonly referred to as tax-sheltered annuities or 403(b) plans. Many of these plans are structured differently from 401(k) plans and other Code Section 401(a) qualified defined contribution plans that are covered by Title I of ERISA. As a result, the 403(b) plan marketplace is unique, resulting in distinctive challenges for these plans in the current regulatory environment.

Over the years, many 403(b) plans have consisted solely of participant-owned annuity contracts and/or custodial accounts. Under these contracts and/or accounts, the plan participants possessed many (and sometimes all) of the contractual rights associated with these accounts or contracts, and the plan participants interacted directly with the service providers for the plan. This type of design resulted in a regime where the 403(b) plan often operated more like a group of Individual Retirement Accounts (“IRAs”) rather than a traditional employer-sponsored plan such as a 401(k) plan.

The Council received testimony that confirmed the presence of unique issues and concerns relevant to 403(b) plans in the current regulatory environment. Testimony indicated that at least some individuals in the benefits community believe that qualified retirement plans under Code Sections 403(b) and 401(k) are nearly identical. While these two types of plans have similar dollar limits and both allow pre-tax and Roth contributions, the differences far exceed the similarities, including the key difference that the sponsors of 403(b) plans are public educational institutions and U.S. tax-exempt organizations. After receiving testimony, the Council believes these differences warrant specific consideration especially in light of the new, expanded compliance requirements for 403(b) plans and the accompanying increased responsibilities of 403(b) plan sponsors and plan administrators. A table showing the similarities and differences between 403(b) and 401(k) plans is documented in Section III of this report.

The Council reviewed certain current issues and challenges facing plan sponsors in administering 403(b) plans and the report focused on the following:

- The differences between large and small 403(b) plans, as well as other qualified plans, with respect to the structure and operation of the plan, and the role of the plan sponsor;

- Confusion among employers with respect to recent guidance issued by DOL and Treasury, and regarding the ERISA status of some 403(b) plans, including the application of the safe harbor exclusion from Title I of ERISA;

- ERISA compliance where individual contracts are used, as well as where a plan uses multiple service providers, including individual contracts held by service providers who are no longer receiving contributions (often referred to as “deselected providers”);

- Issues regarding the in-kind transfer of annuity contracts and certificates to participants, including transfers upon termination of employment or upon the termination of the plan;

- The challenges resulting from introducing an expanded regulatory and compliance scheme to the existing 403(b) plans and the challenges that are unique to 403(b) plans, such as issues encountered with the comprehensive fee disclosure guidance requirements under ERISA Sections 404(a) and 408(b)(2);

- Generally accepted accounting and auditing requirements relevant to the independent audits of 403(b) plan financial statements and the results of the 2009 plan filings with the related audited financial statements.

The Council received testimony from representatives of DOL, Treasury and IRS on the state of 403(b) plan compliance with respect to recent changes in ERISA and tax code requirements. The AICPA provided testimony regarding the independent audit requirements and issues related to required audit procedures. Testimony regarding the 403(b) plan marketplace, specifically in terms of how it has, and may continue to, evolve in light of the significant regulatory changes was provided by representatives of various trade associations that represent 403(b) plans, including the ACLI, ASPPA, ICI, and NTSAA, as well as a survey provided by the Plan Sponsor Council of America (formerly, the Profit Sharing Council of America).

Additionally, the Council received testimony from service providers including representatives from Caplin & Drysdale, Chartered, PenServ, VALIC, and FMR, who testified with respect to their efforts to assist employers and plan sponsors to comply with the recent regulatory requirements, and provided a perspective on how the 403(b) plan marketplace has evolved during this period of significant regulatory change. They also addressed the likely future direction of the 403(b) plan market.

The Council sought to identify differences in “best practices” for the 403(b) plan marketplace and those for the 401(k) plan marketplace. The Council received testimony on these issues from many of the organizations listed above, as well as testimony from the Heritage Foundation, on behalf of Retirement Made Simpler – a coalition formed by AARP, FINRA and RSP. The testimony received from the witnesses was central to the Council’s analysis and discussion of the issues addressed in the report.

The recommendations included in this report focus primarily on options the Council believes will best assist employers, plan sponsors and service providers in completing the transition to full compliance for 403(b) plans, including the new Form 5500 reporting requirements and Section 404(a) and 408(b)(2) disclosure requirements. The recommendations include specific proposals to provide (1) further guidance, information, and tools regarding the ERISA safe harbor exclusion under Title I of ERISA; (2) a compliance “fresh start” that would recognize the lack of any prior requirement for 403(b) plan sponsors to maintain plan-level or plan-related data on certain contracts and/or accounts; and (3) clarification of which individual contracts, certificates, and/or custodial accounts, are or are not, plan assets. The other proposals included in the report focus on a significant need for DOL to review existing 403(b) reporting requirements and their current application, as well as continued outreach to employers and plan sponsors that is designed to help them with the 403(b) plan transition from a historically minimal role, to fulfill the current role that involves a more integral role in plan administration, and compliance.

Recommendations

The Council recommends that DOL should:

- Provide further guidance regarding the safe harbor exclusion from Title I of ERISA for certain qualifying 403(b) plans, including making available to plan sponsors information and/or tools to assist them in determining whether a plan qualifies for the safe harbor exclusion. The guidance should address; (1) the limitations on employer involvement; (2) whether, and to what extent, a group custodial arrangement is permitted; and (3) what happens when a plan ceases to qualify for the safe harbor exclusion.

- Issue guidance stating that any individual contract, certificate under a group contract, or custodial account that is transferred to a former employee ceases to be a plan asset if the employer has no further obligations or involvement. DOL should provide if and when this treatment would apply to similar eligible in-service transfers to a current employee.

- Provide a “fresh start” for 403(b) plans sponsored by private tax-exempt employers with respect to certain reporting and disclosure requirements under ERISA.

- Develop an alternative regulatory financial reporting approach to avoid an adverse audit opinion or a disclaimed audit opinion in cases where the plan sponsor is unable to conclusively identify all contracts that were issued under the plan but held and controlled by the participant either at December 31, 2008 or, if later, the date the plan became an ERISA plan.

- Establish a more comprehensive educational and outreach effort for employers and service providers designed to increase the information available to plan sponsors, particularly small employers, regarding ERISA compliance requirements, plan administration, and best practices for 403(b) plans.

Background

A. The Evolution of 403(b) Plans

Long before ERISA was enacted in 1974, 403(b) plans were already in existence. These plans offered a simple retirement vehicle for employees of public educational institutions and private tax-exempt employers to save for retirement on a tax-deferred basis. At that time, costs and responsibilities were minimal, which made this type of plan affordable for not-for-profit organizations. Employers relied upon insurance companies, the issuers of annuity contracts, to administer the terms of the 403(b) contracts, which included requirements to conform to the applicable requirements of the Code.

As 403(b) plan compliance requirements have evolved, so too have the relationships among the employer/plan sponsor, participant and service providers. However, many 403(b) plans still hold accounts and/or contracts that incorporate greater deference to individual participant control. Current DOL guidance for ERISA plans can be more challenging to apply to 403(b) plans because (1) some 403(b) plans have multiple investment product providers as well as multiple administrators and (2) because some contracts give the investment providers more control (such as control over the investment choices).

In addition, another area of challenge will occur if an employer decided that an investment provider would no longer be authorized to receive contributions (commonly referred to as a “deselected vendor”), and the participant’s account, in many cases, would remain with the deselected vendor unless, and until, the participant chose to transfer their account to another vendor. This practice continues to exist today in many 403(b) plans.

B. A Look at the Features of 403(b) Plans and 401(k) Plans

As more fully discussed in this report, after the enactment of ERISA in 1974, many 403(b) plans were exempt from the requirements under Title I. Even where a 403(b) plan was subject to Title I, many employers continued to have limited involvement and relied on the insurance companies to administer the plan, including, meeting the regulatory compliance requirements. For many years the basic structure of these plans did not change, i.e. the primary relationship was one between the employee and the annuity contract issuer. The employer often had little or no involvement beyond receiving contribution elections from the employee (including designation of the investment provider from what was frequently a number of vendors authorized by the employer), processing deferrals, and forwarding contributions to the contract issuer. As an example, absent any contrary plan restrictions, employees were often free to transfer their accounts to other vendors without the knowledge or involvement of their employer.

In addition to the enactment of ERISA, in1974 Section 403(b)(7) was added to the Code permitting employees to invest in mutual funds held in custodial accounts. As time progressed, and new tax legislation was enacted, 403(b) plans became more similar to 401(k) plans. However, significant differences from 401(k) plans remain both in the operation of the plans and in the applicable regulatory requirements. Again, in July 2007, the Treasury Department issued new regulations designed to bring 403(b) plans closer to the regulatory framework that applies to 401(k) plans. Among other things, the new IRS regulations, placed greater responsibility on the 403(b) plan sponsor to maintain the plan, and required a written plan document to be in place. These new rules became effective January 1, 2009.

Due, in part, to the 2007 changes in the IRS regulations, in November 2007 DOL issued amended regulations eliminating an exemption from the annual Form 5500 reporting and related audit requirements under Title I of ERISA for 403(b) plans. Consequently, effective for the 2009 plan year, 403(b) plans became subject to these reporting and audit requirements. However, there continues to be confusion regarding the application of the most recent regulations and reporting requirements. The Council believes compliance by 403(b) plan sponsors would improve if DOL would reeducate these plan sponsors and provide additional guidance on the application of the new requirements. A comparison of these two types of plans is provided below (data elements generally reflect witness testimony):

403(b) and 401(k) Similarities and Differences |

||

Feature |

403(b) |

401(k) |

|

Employee and employer contribution limits |

Employee deferrals—$16,500 (2011) Age 50 “catch-up”: Added $5,500 (2011)* Other contributions (including deferrals): subject to annual additions limit; 100% of compensation up to $49,000 Long Service “catch-up”: 15 years of service up to an additional $3,000* *Not considered in determining $49,000 annual addition limit. |

Employee deferrals—$16,500 (2011) Age 50 “catch-up”: Added $5,500 (2011)* Other contributions (including deferrals): subject to annual additions limit; 100% of compensation up to $49,000 No provision *Not considered in determining $49,000 annual addition limit. |

|

Eligible employers |

Quite limited: Public educational institutions; private tax-exempt employers qualifying under Code Section 501(c)(3) (generally charitable organizations). |

Generally available for private for-profit employers, private tax-exempt employers, grandfathered public employers. |

|

Permitted investments |

Limited to (i) annuities and (ii) custodial accounts investing exclusively in regulated investment company stock (mutual funds). Can be individual or group contracts or accounts. No trust requirement for ERISA plans: both annuities and custodial accounts qualify as alternatives to a trust under ERISA Section 403(b). |

Trust requirement applies to ERISA plans, with wider range of permitted investments; annuity qualifies as an alternative to a trust, under ERISA Section 403(b), but custodial account does not. |

|

Transfers of individual account balances to another contract and/or account outside of the plan |

Many individual contracts and custodial accounts were created pursuant to Revenue Ruling 90-24. Grandfathered 90-24 contracts and pre-2005 contracts are not required to be included as plan assets for IRS compliance purposes as these are considered individual “standalone” contracts held by the individual participant. Current rules: (a) distinguish between in-plan (“transfers”) and out-of-plan (“exchanges”); (b) both transfers and exchanges are subject to plan control and authorization; (c) generally restrict new standalone 403(b) contracts to distributed contracts. Employer-directed transfers permitted, subject to terms of plan and investment arrangement, however participant control is more prevalent. |

Ability to transfer within the plan or outside of the plan has been, and continues to be, under the control of the plan. Employer-directed transfers more common, especially in the case of adding or deleting investment options offered under the plan. |

|

Number of investment providers |

More common to include multiple investment providers offering annuity contracts and custodial accounts. |

More common to have a single investment arrangement under a single trust or annuity contract. |

|

The ability to maintain an ERISA safe harbor plan (standing alone, or alongside an ERISA 403(b) plan) |

Permitted; common for private tax-exempt employers. |

No comparable provision in ERISA |

|

Applicability of non-discrimination rules to employee deferrals and other contributions |

Elective deferrals: very limited right to exclude. “Universal availability rule” generally requires that deferral opportunity is available to all who are not otherwise excludable. Other contributions: subject to discrimination testing for plans of private tax-exempt (other than “steeple” churches and qualifying church-controlled organizations). |

Elective deferrals: can exclude, subject to age and service caps; must pass average deferral percentage (ADP) test (does not apply to public employers). Other contributions: generally the same as 403(b) |

|

Employer contributions after termination of employment |

Permitted for up to five years. |

Not permitted. |

|

Party responsible for compliance coordination across multiple providers, multiple plans |

Unless a third party is engaged, coordination generally falls to either the employer or the investment provider(s). |

More common to engage a third party administrator, which also could be the investment provider or an affiliate of the investment provider. |

|

Treatment of distributed contracts |

In-kind distributions of annuity contracts permitted under Federal tax rules following a distributable event. |

Same |

|

Form 5500 Reporting |

Limited reporting required prior to 2009, with no trust reports. Thus, no existing documentation to serve as a starting point for complying with new reporting requirements beginning in 2009. |

Detailed reporting required prior to 2009. Trust reports for prior year serves as starting point for subsequent year reporting. Plans funded exclusively with annuities were still required to provide detailed financial reporting that could serve as the starting point for the subsequent year. |

|

Plan audits |

Audits not required prior to 2009. Thus, no trust reports or comparable history to facilitate reconstruction of the past for data needed to establish beginning balances for 2009. Audit challenges include ability to identify “unknown unknowns”; including determining which accounts may be missing (see Transfers). Existing DOL guidance does not relieve auditors from the requirement to verify 2009 opening balances. |

Audits required prior to 2009. Trust reports and other asset information from prior years are available to establish a current year starting balance. |

Summary of Testimony, Council Discussion and Rationale for Recommendations

A. Safe Harbor Exclusion from Title I

Provide further guidance regarding the safe harbor exclusion from Title I of ERISA for certain qualifying 403(b) plans, including making available to plan sponsors information and/or tools to assist them in determining whether a plan qualifies for the safe harbor exclusion. The guidance should address: (1) the limitations on employer involvement; (2) whether, and to what extent, a group custodial arrangement is permitted; (3) what happens when a plan ceases to qualify for the safe harbor exclusion.

Section 403(b) plans of private tax-exempt employers are subject to the requirements of Title I of ERISA unless the plan qualifies for one of the two exclusions from Title I. Pursuant to 29 CFR Section 2510.3-2 a safe harbor exclusion from Title I has been available since the 1970’s for 403(b) plans that consists solely of nonforfeitable voluntary employee contributions and earnings thereon, provided that employer involvement is sufficiently limited, and that plan participants are provided a sufficient selection of investments and providers.(2) Testimony received by the Council identified some important challenges faced by private tax-exempt employers who currently offer, and are seeking to maintain, 403(b) plans under the safe harbor exclusion and to comply with the tax regulations that impose additional requirements on those plans. The challenges include additional administrative burdens, costs and a lack of clarity regarding the current application of the ERISA safe harbor.

The safe harbor creates a balance between important Title I protections for plan participants and the reality that some not-for-profit employers cannot afford the cost of Title I compliance. This may be due to the fact that many of these employers are small organizations with minimal budgets but have a desire to make salary deferral retirement savings options for their employees. As part of the balance between Title I protections and recognition of the unique aspects of certain 403(b) plans, the burden of establishing eligibility for the safe harbor exclusion generally rests with the sponsoring employer. If the burden is satisfied and the safe harbor exclusion applies, the plan is not considered to be “established or maintained by an employer” for purposes of Title I.

The application of the IRS 403(b) regulations, issued in 2007 and effective in 2009, generally impose greater employer oversight responsibilities and compliance requirements, and has given rise to several questions regarding the interaction of the tax requirements and the Title I safe harbor exclusion. In addition, some additional related questions have been highlighted. Testimony received by the Council identified key areas where guidance from DOL could better facilitate compliance with the recent 403(b) regulations in a manner that is consistent with the “letter and intent” of the 403(b) safe harbor exclusion under Title I.

In Field Assistance Bulletins issued in 2007, 2009, and 2010, (“FAB”) DOL has made efforts to clarify the interaction of the Title I safe harbor exclusion and the general ERISA requirements pursuant to new tax regulations as follows:

- FAB 2007-02: Confirmed that a 403(b) plan complying with the 2007 tax regulations could still qualify for the Title I safe harbor provided that the plan was designed and administered consistent with the safe harbor. This condition can be verified only by a review of the facts and circumstances of the specific case.

- FAB 2009-02: Focused primarily on ERISA 403(b) plans and the necessity to include certain annuity contracts for purposes of Form 5500 reporting, and the associated annual audit of the plan’s financial statements.

- FAB 2010-01: Addressed some key safe harbor requirements, including plan design, engagement of a third party administrator, reasonable choice of investments and providers, deselection of providers, and employer-initiated asset transfers.

The testimony received underscored the importance of the availability of the safe harbor alternative for eligible employers, particularly to facilitate 403(b) plan coverage among smaller tax-exempt employers, and generally to balance the cost, compliance considerations, and maintaining important participant protections. The compliance considerations were highlighted in testimony received from DOL representatives who noted that the safe harbor is an exception from the ERISA rules that otherwise apply to many 403(b) plans, 401(k) plans, and other qualified retirement plans. In addition, the importance of making the safe harbor exclusion available to many private tax-exempt employers was highlighted in testimony from other witnesses who represented the private sector including Ms. Cook, Ms. Chism, Mr. Skillman, and Mr. Architect. Although these witnesses were not asking that DOL expand the safe harbor, they did encourage the issuance of additional clarity on the scope of the safe harbor, and providing relief for employers who took good faith actions to meet the compliance requirements of the new regulations that apply to 403(b) plans.

The following is a summary of points highlighted by witnesses who testified regarding issues relating to the Title I safe harbor exclusion for 403(b) plans. In some instances, the testimony included proposed recommendations to DOL:

- Witnesses (including Mr. Skillman, Ms. Cook, Ms. Chism, and Ms. Jonas) addressed concerns that employers who took certain actions they believed to be nondiscretionary, such as permitting loan repayments through payroll deductions, and/or applying mathematical loan limitations and specific hardship rules under the plan, whether the actions were taken by the employer or through a third party administrator, have been later informed that such actions are essentially deemed discretionary. Thus, an otherwise qualifying safe harbor plan would not meet the requirements for safe harbor status.

The witnesses urged the Council to recognize a distinction between the role of designing the plan structure (including adopting clear standards for loans and hardships from the plan), and the role of making discretionary determinations under the plan. This is a distinction that DOL also has made with respect to settlor functions. The witnesses urged the Council to propose that DOL reconsider its current interpretations of discretionary and non-discretionary actions of a safe harbor plan and provide additional guidance that would recognize certain activity to be consistent with the Title I safe harbor exclusion, including the following activities:

- Loan repayments by payroll deduction, whether imposed by the investment provider or under the terms of the plan;

- Application of mathematical loan limitations; and,

- Ministerial application of hardship withdrawal rules clearly set forth in the plan document that includes designing plan standards for such distributions.

Discussion between the Council and witnesses highlighted the challenges employers face when applying the Title I safe harbor rules and coordinating compliance, for example, loan limitations and hardship withdrawals across multiple plans maintained by the same employer, particularly where at least one of the plans is intended to be a safe harbor plan. Ms. Cook specifically encouraged DOL to examine the necessity of certain employer actions, in good faith, to handle necessary compliance activities in a manner that was consistent with the safe harbor requirements before DOL issued guidance in FABs 2009-2 and 2010-1. Ms. Cook urged DOL, in such cases, to afford these plans the safe harbor status, at least for a limited transition period after any guidance is issued.

The Council believes these proposed recommendations would further achieve the goal of the Title I safe harbor, and maintain the balance between participant protections, and the additional needs and challenges faced by the employers who sponsor these 403(b) plans.

- In his testimony, Mr. Architect noted the reference to an “open architecture custodial account” in FAB 2010-01 (Q&A 16). This reference not only addressed the potential for having a single provider in a safe harbor plan, but implicitly suggests that a group custodial account would be permitted in such a plan. Certain employers and service providers have presumed that group custodial accounts are permitted under the safe harbor even prior to the issuance of FAB 2010-01. Discussion between the Council and some of the witnesses highlighted that although the safe harbor regulation references group annuity contracts, the regulation is silent with respect to group custodial accounts. The Council believes that a clarification of whether a group custodial account is permitted in a safe harbor plan is necessary in order to provide certainty to, and enable employers to, design plans that offer valuable employee benefits consistent with the requirements of Title I and the 403(b) safe harbor, respectively.

- Discussions between witnesses (Mr. Skillman and Mr. Canary) and the Council, following the presentation of testimony, highlighted the additional issue regarding plans that previously qualified for the Title I safe harbor exclusion and subsequently became subject to Title I whether intentionally or by inadvertent error. The Council believes that in the interest of providing relief for plan administration and promoting plan efficiency for these plans, DOL should provide guidance stating that only the contracts and accounts included in the plan immediately prior to the disqualifying event (i.e. the event that caused the plan to become subject to Title I) should be considered assets of the plan that is now subject to Title I. Accordingly, a contract or account that was properly excluded from the plan when the plan qualified for the Title I safe harbor, such as a contract with a provider deselected by the employer prior to 2005 (consistent with IRS guidance), should not be considered an asset of the plan after the plan has become subject to Title I of ERISA. The Council believes this clarification would work to the benefit of plan sponsors, and provide for less complex and costly administration of the plan with no resulting reduction of participants’ protections.

The Council agreed that the exclusions under FAB No. 2009-2 should not be imposed for periods before the plan became subject to Title I of ERISA. The Council believes that this type of retroactive application would result in uncertain and negative incentives for employers to sponsor these plans. The Council also believes that DOL should clarify that these accounts never became assets of the resulting Title I plan. In addition, the Council believes that this clarification would generally decrease the hardship on employers who sponsor these plans, and specifically reduce the burdens associated with auditing the financial statements of these plans.

- In addition, the Council recommends that DOL make available to employers both additional information and tools to aid in determining whether a plan meets the requirements for the safe harbor exclusion. The 2010 and 2011 403(b) Plan Surveys provided by the Plan Sponsor Council of America highlighted, in statistics, the same point the Council heard from multiple witnesses, which was that many employers are having difficulty determining whether their plan meets the safe harbor requirements, or whether the plan is subject to Title I of ERISA.

The Council also considered, but is not recommending, that DOL permit the inclusion of an automatic enrollment feature within the context of an ERISA safe harbor 403(b) plan. The majority of Council members concluded that automatic enrollment would require actions typically performed by a plan sponsor/fiduciary (e.g., designation of a default investment alternative), and consequently, an automatic enrollment option in the plan may not be viewed as voluntary even in light of the participant’s right to opt out of the automatic contributions.

B. Status of Certain Individual Contracts, Certificates Under a Group Contract, or Custodial Account

The Council recommends that DOL issue guidance stating that any individual contract, certificate under a group contract, or custodial account that is transferred to a former employee ceases to be a plan asset if the employer has no further obligations or involvement. DOL should provide if, and when, this treatment would apply to similar eligible in-service transfers to a current employee.

As previously discussed, ERISA covered 403(b) plans are funded through individual annuity contracts or individual custodial accounts. The plan sponsor or plan administrator may have very limited rights over such contracts or accounts, and in such cases the question becomes whether the individual contracts or accounts should be considered assets of the ERISA plan once a participant has terminated employment.

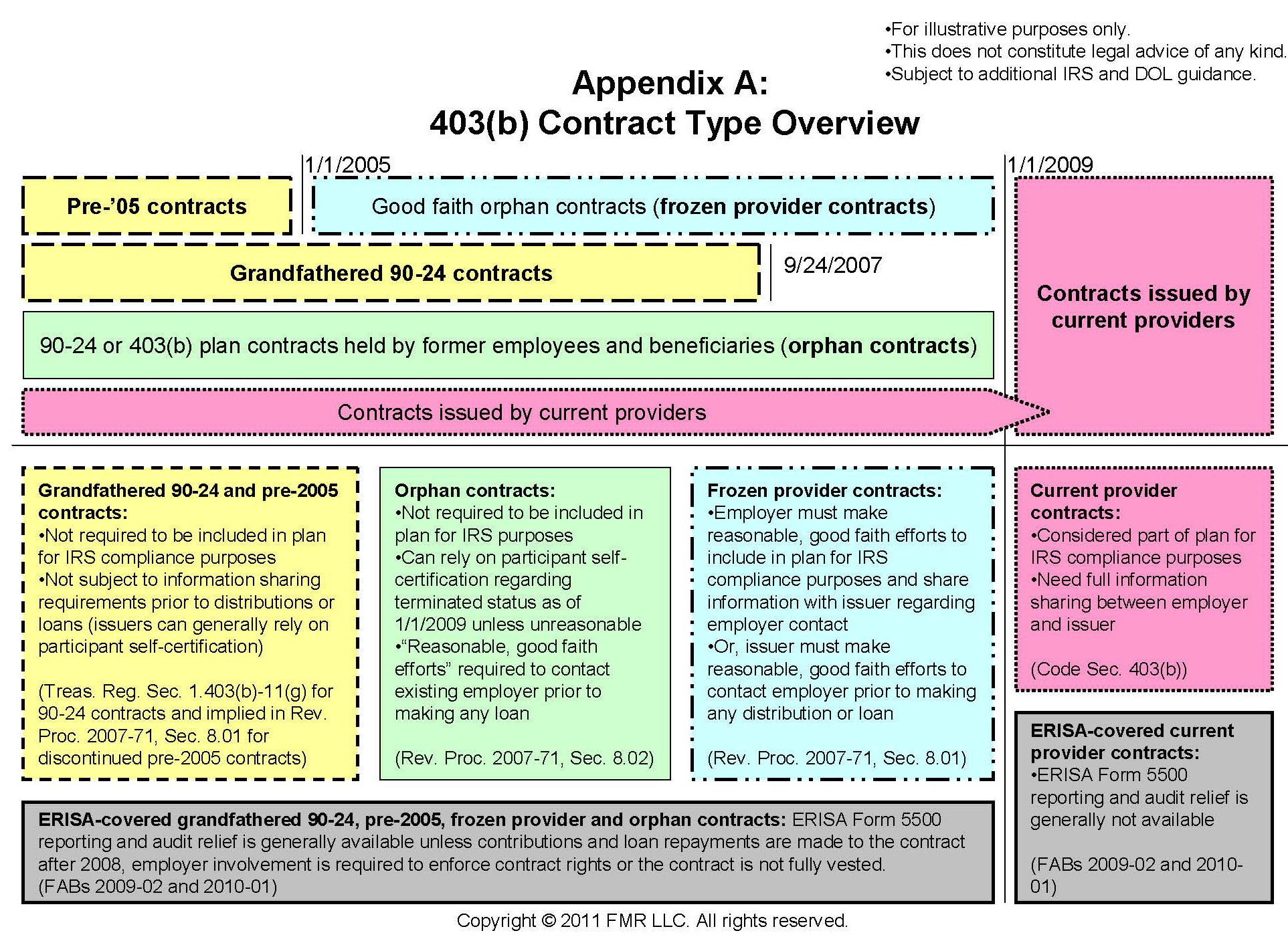

Under Revenue Ruling 90-24 (obsolete in 2007), another aspect related to these contracts and/or accounts was the ability of a participant to select an alternative vendor not authorized to receive employer contributions. Additionally, if the plan sponsor chose to discontinue contributions to a vendor (deselected vendor), the participant had the right to continue to hold these orphaned contracts and/or accounts. Generally and prior to regulations effective in 2009, these contracts and/or accounts were not required to be included as plan assets for IRS compliance purposes. (See Appendix A)

DOL’s regulations specifically provide that an individual is not a participant, and thus an individual's account is not a plan asset, where:

- An individual annuity contract or a certificate under a group annuity contract has been issued to an individual who is not a participant covered under an employee pension benefit plan, and

- The entire benefit rights of the individual are fully guaranteed by an insurance company and are legally enforceable solely between the individual and the insurance company.(3)

The Council's recommendation concerning the status of these specific individual contracts and certificates that have been issued to former employees is consistent with this regulation, although DOL has not issued interpretive guidance with respect to this regulation. More specifically, for a former employee whose account is represented by such a contract or certificate, whether previously or newly transferred, and where the employee is not entitled to any further contributions under the plan, such employee would look to the contract for a guarantee of benefit rights to be provided and to the insurance company for enforcement of the contract. This would be true with respect to either a fixed or a variable annuity. The additional portion of the Council's recommendations regarding the status for in-service transfers of a contract or certificate to a participant, and with respect to the transfer of individual custodial accounts, also is consistent with the objective of the regulation, but the Council acknowledges that it may extend beyond the legal scope.(4) Thus, it becomes critical that such relief be provided by DOL issued guidance.

DOL has clarified that this provision would apply only if the employee is not accruing any additional benefits. As a result, participant status would continue to apply (or restart) with respect to individual contracts, certificates and custodial accounts that were delivered following separation from service if and when, an individual is rehired, and contributions recommence to the previously distributed contract, certificate or account. Similarly, with respect to plan asset determinations, the delivered individual contracts, certificates and custodial accounts would become plan assets if, and when, the individual becomes eligible to contribute and begins contributing to that contract, certificate or custodial account again.

The Council believes that in such a case plan asset status should be based on who controls the contract and/or account, and that any contracts and/or accounts where the essential elements of individual ownership remain in effect because the individual has fully vested rights and the plan sponsor does not have material retained rights with respect to that individual contract or custodial account.

As a result, the Council recommends that DOL provide guidance that would exclude from the definition of plan assets individual annuity contracts, certificates and custodial accounts that were:

- Delivered to former employees following separation from service, where the plan sponsor has not retained any material rights.

- Delivered to current employees as a result of in-service distribution provisions (such as after reaching age 59½), where the plan sponsor has not retained any material rights.

The Council found additional support for this recommendation in testimony provided by Ms. Elena Chism, of ICI and Ms. Weiyen Jonas, FMR that described the variety of contractual relationships found among many 403(b) plans (a version of the chart they provided with their testimony is attached in Appendix A). Ms. Chism and Ms. Jonas specifically highlighted the issues related to individual contracts and accounts similar to those described above. They requested relief that would provide for ease of plan administration if such individual contracts and accounts were removed from the definition of plan assets. They specifically cited the challenges involved where such individual contracts and accounts are held to be “designated investment alternatives,” which would trigger certain investment-related disclosures under ERISA Sections 404(a) and 408(b)(2). The witnesses testified that from the participant’s perspective, applying Section 404(a) disclosure requirements of quarterly and annual communications is particularly unnecessary given the direct participant-to-service-provider relationship inherent in the individual contract or custodial account.

The Council’s recommendation concerning the status of these specific individual contracts and certificates for former employees is consistent with the terms of the regulation set forth in footnote 3, although DOL has not issued interpretive guidance with respect to this specific regulation. Similar to the IRS rules, such DOL guidance would extend to contracts and certificates already held by a participant, at such time as the participant was no longer employed by the plan sponsor. The Council’s additional recommendations with respect to in-service distributions of such contracts and certificates, and with respect to distributions of individual custodial accounts, are consistent with the objective of the regulation but the Council is aware it extends beyond the legal scope of the current regulation.(5) The Council’s recommendation is limited to individual contracts, certificates, and accounts and is intended to offer guidance, similar to existing tax code guidance which treats custodial accounts on the same basis as annuity contracts for many purposes under the 403(b) regulations. Under the recommended guidance, transactions with respect to such distributed contracts, certificates and accounts would be solely the responsibility of the participant and the investment provider.

C. Fresh Start for Certain 403(b) Plans

Provide a “fresh start” for 403(b) plans sponsored by private tax-exempt employers with respect to certain reporting and disclosure requirements under ERISA.

As illustrated in the table included in section III of the report, there are substantial differences between 403(b) and 401(k) plans, including, the fact that the Code does not require 403(b) plan assets to be held in a trust. Furthermore, as noted by several witnesses, including Mr. Szostek, Ms. Cook, and Mr. Architect, prior to the final regulations becoming effective in 2009, there was no requirement for Section 403(b) plan sponsors to maintain plan-level or plan-related data. Section 403(b) plans often allowed for individual annuity contracts with individual rights, where, pursuant to Revenue Ruling 90-24 participants could effectuate a transfer of their account without plan sponsor involvement. Plan sponsors were not required to maintain data and the regulatory structure allowed for, and some might argue even promoted, limited plan sponsor involvement. The normal historical business practice consisted of an open architecture structure whereby the plan sponsors would send salary deferrals to an investment provider chosen and designated by the participant.

As Mr. Architect discussed, while there may be some similarities between 403(b) and 401(k) plans, there are also distinct differences. He noted that the unique status of private 403(b) plans derives from the fact that only not-for-profit organizations utilize such plans. Most of these 403(b) plan sponsors lack the resources to engage legal, accounting and recordkeeping professionals to help them with any applicable ERISA requirements. The same concerns were raised by witnesses with regard to the importance of the safe harbor, particularly as smaller not-for-profit organizations that maintain ERISA 403(b) plans frequently rely more heavily upon their own staff and their investment providers for assistance in complying with reporting, disclosure and audit requirements. The most recent regulations do not include accommodations designed to recognize the key unique characteristics of these 403(b) plans.

As Ms. Cook noted, it may be impossible for certain plan sponsors to comply with any ERISA requirement that compels 403(b) plan sponsors to have data on all plan participants, annuity contracts, and custodial accounts for periods prior to January 1, 2009. For many of these plans, while they have data on participant accounts with current providers, there will be some account data for accounts with former providers, or with providers that have received Revenue Ruling 90-24 transfers that the plan sponsor will never be able to obtain or compile. These employers cannot manufacture data they do not possess and have not collected. Even for accounts known to the plan sponsors, the maintenance of centralized plan-level records has not been required, and many of the plans do not have such records. Ms. Cook noted that because these plan sponsors do not have a centralized source of historically reliable data, anything that requires plan sponsors to go back to a centralized source of historically reliable data prior to January 1, 2009, can be very difficult, if not impossible, to satisfy.

Several witnesses acknowledged that DOL provided helpful guidance in FABs 2009-2 and FAB 2010-1 with respect to the unique reporting and disclosure challenges faced by 403(b) plans. Mr. Szostek explained how the guidance removed, for Form 5500 reporting but not financial statement reporting purposes, a key group of contracts that predate the effective date of the final 403(b) Treasury regulation. This guidance applies to contracts for which the employer has no active involvement, obligation, authority, or control. As an aside, Mr. Szostek argued, and the Council agreed, that to further simplify the plan’s on-going compliance and reporting, DOL should consider extending this treatment to contracts held by former employees (see recommendation B). Also, he acknowledged that there should be “reasonable paths to compliance” for struggling 403(b) plan sponsors with respect to meeting the reporting, audit and disclosure requirements.

The historical lack of centralized data creates unique challenges for 403(b) plan sponsors. Many witnesses urged the Council to recommend that DOL establish a “go-forward” date, for all reporting and disclosure requirements (i.e., Form 5500, Sections 404(a) and 408(b)(2)) where a 403(b) plan that is sponsored by a private employer would be responsible for having the data to show account balances of active participants. Such a “go-forward” rather than a “look-back” date would alleviate the concern that ERISA compliance requirements surprised 403(b) plan sponsors who were not historically subject to the ERISA reporting rules, and cannot, and should not, have to try to collect data they were historically not required to maintain. If for example, DOL were to indicate that, beginning on January 1, 2012, all 403(b) plan sponsors subject to ERISA will be required to comply with all reporting and disclosure requirements for all active participants and other eligible employees, then the plan sponsors could work with their vendors to ensure that they build systems to maintain the required data. But the retroactive application of data collection and reporting requirements for these earlier periods creates burdens on the plan sponsors that are likely to far exceed any improvement in participant protections, plan administration and compliance or incentives for these employers to maintain the plan.

DOL, understandably, has legitimate concerns in resetting the ERISA fiduciary clock for any plan sponsor. ERISA’s fiduciary duties are of the highest standards in the land and afford participants considerably key rights and protections. Furthermore, DOL has indicated that they were pleased with the results of the 2009 Form 5500 filings with respect to the audit reports, and DOL stated that they are not convinced there is an existing problem that needs to be solved. In fact, Mr. Ian Dingwall, Chief Accountant of EBSA, reported that his office has not identified many filings which reported issues and/or concerns with identifying opening balances on the audits that were a result of the lack of historical data. In addition, both Mr. Dingwall and Mr. Joe Canary, Director of the Office or Regulations (EBSA), highlighted the fact that 403(b) plan sponsors should not have been surprised about reporting requirements because DOL engaged in concerted educational outreach, starting in 2007, and delayed the effective date of the applicable regulations until 2009.

In addition to DOL's valid concerns, there is, or was, a perception by regulators and industry professionals that the 403(b) plan market represents a sort of unorganized and noncompliant landscape. There were several witnesses, including Mr. Skillman, who disagreed with this assumption based on his over 35 years of 403(b) plan experience. Similarly, Mr. Architect, Vice President of compliance and market strategy for VALIC, and formerly of the IRS, indicated that the final 403(b) regulations addressed most material concerns. In fact, Mr. Architect testified that the compliance concerns being discussed at the hearing are more issues for small employer plans rather than an issue specific to 403(b) plans, and further added that, in his experience, he hadn’t seen the problems being more pronounced with 403(b) plans than 401(a) plans.

In any event, most witnesses posited that most private 403(b) plan sponsors have neither the monetary nor the personnel resources, or the fiduciary know-how to become well versed in the ERISA roles and responsibilities as they apply to the plan. Thus, the witnesses testified that they saw no harm, and indeed great good, in providing less stringent rules or transitional relief for 403(b) plans with respect to certain reporting and disclosure requirements. In fact, the Council agreed with Ms. Cook, who noted that because a majority of 403(b) accounts are funded via individual annuity contracts, with individual rather than plan-level rights, as well as individual versus plan-level statements (i.e., participants receive individual certificates or contracts as the legal owner of the contract), transition relief on the plan-level reporting requirement does not create a significant disadvantage to participants who hold the certificates or individual annuity contracts.

The Council believes that 403(b) plan fiduciaries and participants would greatly benefit if DOL provided an appropriately selected future date to establish beginning balances for plan purposes with respect to those 403(b) plans that are already subject to ERISA, or alternatively, the first day of the plan year in which the plan becomes subject to Title I.

In addition, the Council believes that DOL should implement this recommendation because of the stated interest in helping this group of employers through educational outreach, and because the plan-level reporting and disclosure requirements do not provide an enhanced benefit to participants who hold the certificates and individual annuity contracts. As a result, the Council recommends that DOL provide this go-forward “fresh start” transition relief to assist these not-for-profit sponsors of 403(b) plans to bring their plans into compliance.

D. Alternative Regulatory Financial Reporting Approach

The Council recommends that DOL develop an alternative regulatory financial reporting approach to avoid an adverse audit opinion or a disclaimed audit opinion in cases where the plan sponsor is unable to conclusively identify all contracts that were issued under the plan but held and controlled by the participant either at December 31, 2008 or, if later, the date the plan became an ERISA plan.

As previously mentioned, the tax regulations issued in July 2007 significantly updated and changed the tax compliance environment for 403(b) plans. In November 2007, DOL issued amended regulations eliminating an exception from annual Form 5500 reporting and audit requirements under Title I of ERISA that were previously granted to 403(b) plans. After this action was taken, ERISA 403(b) plans became subject to the same Form 5500 reporting and audit requirements that applied to 401(k) plans. This requirement became effective for the 2009 plan year Form 5500 filings and subsequent years with respect to 403(b) plans.

Under the current regulations, 403(b) plans with 100 or more eligible participants at the beginning of the plan year are required to have the plan’s financial statements audited and attached to the Form 5500. Under the regulations, audited financial statements must include the current year’s statement of net assets and a comparative statement of net assets for the previous year. This requirement, along with the initial plan year audit procedures, presents a problem for certain 403(b) plan sponsors due to the fact that many such plan sponsors did not maintain, nor were required to maintain, the appropriate participant and investment records (see recommendation C). Many plans have inadequate records for financial statement reporting purposes due to the inability of the plan sponsors to determine what contracts were in existence prior to December 31, 2008.

The Council believes that it would be appropriate for DOL to develop an alternative regulatory financial reporting approach that would be adopted by 403(b) plans that have been unable to prepare complete financial statements in accordance with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and Generally Accepted Auditing Standards (GAAS). This alternative reporting approach would be available to the plan sponsors who have been unable to obtain a complete population of contracts and transactions due to reliance on IRS Revenue Ruling 90-24 that previously allowed 403(b) participants to initiate a transfer of their 403(b) contracts and accounts from a vendor that was offered under their employer-sponsored plan to a vendor outside of the plan. In addition, if a plan sponsor decided that an investment provider was no longer authorized to receive contributions (“deselected vendor”), in many cases, the participant’s account would remain with the deselected vendor unless, and until, the participant chose to transfer the contract or account to another vendor. Under both of these circumstances an inability for the plan sponsor to maintain sufficiently accurate participant and plan records was created. Additionally, the employers could rely on FAB No. 2009-02, which provided for some transitional reporting relief for certain pre-January 2009 inactive contracts. FAB 2009-02 allowed the contracts discussed in this section to be excluded from plan assets for purposes of Form 5500 reporting, but issues remained even in light of the FAB’s transitional relief regarding the ability to exclude the contracts for purposes of the financial statement requirements. Under GAAP, the audit is of the plan’s financial statements includes all plan assets regardless of the assets that are reported on the Form 5500. The exclusion of these plan assets on the Form 5500, whether know or unknown, caused issues with the audit and reporting standards for opening balances and the completeness of the participant population, as well as completeness of the assets held by the plan as of January 1, 2009.

The Council received testimony from Mr. Canary and Mr. Dingwall, who testified regarding the issues arising from, and results of, the 2009 Form 5500 filings for 403(b) plans. Mr. Dingwall indicated that DOL received approximately 21,300 403(b) plan filings of which approximately 5,800 attached audit reports. Of those filings with audit reports, Mr. Dingwall noted that “approximately 81% of the filings made no reference to opening balance problems,” thus leaving approximately 19% with either an opening balance problem or some other issue. Additionally, Mr. Dingwall noted that approximately 850 plans filed without an accountants report which appeared to be required as part of the filing. The Council was made aware that beginning in 2009, all Form 5500 filings are now electronically available on the EBSA website. Anyone can search the website for a specific filing for a 403(b) plan and can review the attached financial statements and auditor’s report.

Additional information provided by the Plan Sponsor Council of America’s 2011 403(b) Plan Survey showed that of the 712 plans surveyed, 51.2% had an independent plan audit. It should be noted that of the 712 plans surveyed, 288 plans had less than 50 active participants, yet 20.5% of the plans in this category had an audit. This would lead the Council to believe that either the plan sponsor did not understand the audit requirement, or that the plan had significant non-participation, inactive participants, or unknown terminated plan participants. The Council learned that the average cost for an audit in this category averaged from $5,000 to $15,000, with 2.9% costing more than $30,000— a very expensive undertaking for a small, not-for-profit organization.

Other testimony from Mr. Bob Lavenberg, representing the AICPA, indicated that the “plan-asset-exclusion” was not well understood, confusing, and caused many plan sponsors to incur additional audit fees or internal costs in their effort to deal with the missing or excluded contracts, and lack of having sufficient accounting records. Additionally, Mr. Lavenberg stated that many not-for-profit organizations felt that a disclaimer of opinion, due to the lack of sufficient accounting records, could alarm participants about the management of the plan and also could adversely impact the organization’s ability to raise funds and/or obtain grants. This issue is not unique to small employers as many large 403(b) plans either received adverse opinions, or the auditor disclaimed an opinion on the financial statements of the plan. These types of opinions could negatively affect the plan sponsor’s organization as well.

In discussing his testimony with the Council, Mr. Lavenberg indicated that removing these old contracts from the plan would help the plan sponsor both from a recordkeeping and an audit perspective. He stated that the AICPA has had discussions with DOL, and others, regarding the possibility of developing alternative reporting methods that would not only be more practicable for a segment of 403(b) plans, but also would allow for a more meaningful audit opinion to be issued for the plan. The Council believes that one such alternate approach would be to have the auditor opine on the financial information contained on Schedule H of the Form 5500 rather than on the information that should be contained in the plan’s financial statements.

In their testimony, both Ms. Diehl, President of PenServ Plan Services, Inc., and Mr. Lavenberg pointed out that without some relief in this area there will continue to be confusion regarding the definition of a plan asset for reporting purposes. They further stated that in their efforts to minimize the potential for a compliance violation, the employers are more likely to terminate or freeze the plan, thereby leaving more employees without the benefit of some type of retirement savings. Ms. Diehl and Mr. Lavenberg pointed out that complying with the audit requirements will continue to be a challenge, and will add unnecessary expense and complexity, if DOL does not clarify the treatment of these old contracts. More specifically, they said DOL should clarify whether these contracts are, or are not, plan assets and whether the participants are, or are not, considered participants of the plan. They pointed out that the almost meaningless audit reports (disclaimed opinions for inadequate records) that are being issued currently will continue well into the future unless the current reporting model is modified to address these issues, as the earlier inaccurate information will continue to form the foundation of the reporting process. Ms. Diehl specifically proposed that a committee of industry experts be set up to review and modify the existing audit guidelines for 403(b) plans, taking into consideration the differences between group and individual contracts, and how these plans differ from 401(k) plans.

The Council believes that, at a minimum, DOL should reinforce its position regarding non-enforcement when an adverse opinion or a disclaimer is issued, and should acknowledge that DOL is fully aware that without any change these types of reports will continue to be issued well into the future.

The Council believes that in order for plan sponsors to move forward with respect to the administration and compliance of the plans discussed herein, that it is critical for DOL to clarify when a contract should be excluded, when the contract should not be excluded, and in such a case what can be done to remedy the situation. In addition, the Council recommends that DOL create an alternative regulatory financial reporting approach for 403(b) plans that have been unable to prepare complete financial statements in accordance with GAAP and GAAS due to unobtainable information.

E. Comprehensive Educational and Outreach Efforts

The Council recommends that DOL establish a more comprehensive education and outreach effort for employers and service providers designed to increase the information available to plan sponsors, particularly small employers, regarding ERISA compliance requirements, plan administration, and best practices for 403(b) plans.

The change in reporting requirements for 403(b) plans that became effective for plan years beginning on or after January 1, 2009, resulted in a wide range of questions and concerns for plan sponsors, employers and service providers. As previously discussed, DOL provided guidance in three FABs that addressed a variety of issues related to both the new reporting requirements, and the application of Title I to 403(b) plans. However, even in light of this guidance, the Council heard through testimony provided by several witnesses that questions continue with respect to these plans.

In her testimony, Ms. Cook stated that her company continues to receive requests from employers seeking their assistance with the filing of Form 5500s, and bringing the plans into compliance. The Council had reason to believe this to be true, as both Mr. Skillman and Ms. Diehl testified that smaller employers were less familiar with the reporting and other ERISA compliance requirements, and therefore, were less likely to be able to bring their plans into compliance. Additionally, Ms. Diehl noted that checklists and model documents are needed, particularly for smaller non-for-profit organizations, and that more Q’s and A’s should also be provided on the EBSA website.

The 2010 and 2011 403(b) Plan Surveys from the Plan Sponsor Council of America showed that some plan sponsors, particularly small employers, may not be sufficiently knowledgeable of the structure of their plans or the applicable regulatory requirements. In the 2011 Survey, almost 20 percent of the respondents with plans covering fewer than 50 active participants did not know whether their plan was covered by ERISA. Conversely, only four percent of the respondents with plans covering between 50 and 199 active participants did not know the ERISA status of their plans. Further, more than half (57%) of respondents with plans covering fewer than 50 active participants did not know what type of agreement(6) was the funding vehicle for the plan. Both surveys showed that about one in four respondents with plans covering fewer than 50 active participants used their own internal staff as the recordkeeper for the plan.

In light of the on-going issues, lack of clarity, and sometimes confusion regarding the reporting and disclosure requirements and the scope of the Title I safe harbor exclusion, the Council believes that DOL should provide, on the EBSA website, additional educational information specific to 403(b) plans, their sponsors, and service providers. The Council believes that doing so will help assure that plan participant interests are protected, and it will help plan sponsors to better communicate with their plan participants. Some materials suggested by the Council could include FAQs or checklists, and tools designed to assist plan sponsors in determining whether a plan qualifies for the Title I safe harbor exclusion. One possible tool the Council believes could be helpful is a questionnaire designed to help identify key decision points that are crucial in assisting employers, and their counsel, in making the necessary determinations relevant to qualification under the Title I safe harbor exclusion, or the application of Title I to the plan. Also, the Council believes it would be helpful to have educational materials that focus on the smaller tax-exempt employers because, as the Council heard in testimony, many of these plan sponsors are unable to readily obtain information on the regulatory changes and the impact on these changes on their plans.

As indicated in a letter to the Council, from the Prince Group, in order for plan sponsors to satisfy their fiduciary responsibilities, best practices need to be adopted by 403(b) plan sponsors. A proper governance structure necessitates the need for further education regarding plan administration, investment policies, required skill sets, and prudent decision making.

The Council recommends that DOL consider different ways to reach out to the 403(b) plan sponsor community in order to provide the educational information. Possible avenues to explore could include:

- Regional forums for plan sponsors to discuss unique aspects of 403(b) plans, including employee communications, administrative practices, auto-enrollment, and compliance matters. These forums could be held with the support and participation of other professional associations for non-profit organizations.(7)

- Outreach to service providers who work with 403(b) plan sponsors such as recordkeepers, investment product vendors, and investment advisors.

Conclusion

After receiving testimony and extensive deliberations, the Council concluded that core issues for the administration and on-going compliance of certain 403(b) plans continue to exist. In light of the recently effective regulatory changes for these plans, the plan sponsors continue to struggle with the desire to provide tax-favorable retirement saving options to their employees versus the overwhelming cost, time commitment, and complex regulatory environment for the plans. In many cases, the plan sponsors want to continue to offer this benefit to their employees but need help in doing so. It is in this light that the Council provided the recommendations contained in this report. The Council understands the need for DOL to review and assess the recommendations to determine what, if any, can be implemented without further action by the Council, whether DOL has sufficient information to proceed, and whether additional involvement of the Council would be necessary.

Appendices

Appendix B: Witness Summaries

Council members prepared the following summaries of witness testimony. A copy of all written witness statements that were submitted can be found at www.dol.gov/ebsa/aboutebsa/erisa_advisory_council.html.

Bob Architect, Vice President of Compliance and Marketing Strategy The Variable Annuity Life Insurance Company (VALIC)

Mr. Architect, a former IRS regulator who specialized in working with 403(b) plans from 1975 through 2009, described the history and background of 403(b) plans from their creation in 1958. Early on, he said the 403(b) landscape was somewhat like the “Wild West” with little statutory structure. At this time, 403(b)s were essentially thought of as individual accounts that consisted of a direct contract between an employee and annuity provider. Practices could vary tremendously, for example, there were no rules for when distributions were required to begin and there were contracts where annuitization began at age 90. Over time, this landscape evolved as a result of changes in 403(b) regulation. Most significantly, 403(b) plans are now regarded as employer plans.

Mr. Architect emphasized that while 403(b) plans have come to resemble 401(k) plans in many ways, an important distinction is the underlying 403(b) community: the not-for-profit world is extraordinarily compliant, has limited resources, and is a community that does good. Mr. Architect stated that in drafting the most recent regulations, the IRS tried to take these distinctions into consideration.

In response to questions, Mr. Architect explained that having many providers was very common in the earlier years because plans were considered to be the plan of the individual, and employers were often responsive to employees’ requests to add additional providers. Under today’s increased regulatory framework, and with “open architecture” in the market place whereby one provider can offer multiple options, the number of different providers used by each employer is falling.

In terms of areas that can still be addressed, Mr. Architect mentioned that there should be clarification of what happens to the contracts serviced by deselected providers – how long are these contracts part of the plan? Finally, Mr. Architect stressed that, in light of the unique challenges posed by recent expansions of DOL rules as applied to 403(b) plans, it is important to know what abuses or failures these new requirements are intended to prevent.

William Bortz, Associate Benefits Council, Department of the Treasury and

Sherri Edelman, Senior Tax Law Specialist, IRS Davison of Employee Benefit Plans

Mr. Bortz noted that there are many similarities under US tax rules between 403(b) and 401(a) qualified plans but only three major differences: (1) 403(b) plans are limited to certain types of employers and employees and have specific funding arrangements, (2) 403(b) plans are subject to a universal availability requirement for elective deferrals rather than the average benefit test used for 401(k) plan elective deferrals, and (3) there are different consequences for compliance failures for 403(b) plans. He discussed a number of key developments in the 403(b) tax rules, including Revenue Ruling 90-24 (which previously allowed for transfers to a secondary vendor, frequently without employer involvement), Revenue Ruling 2007-71 (transitional relief required on account of increased employer involvement), and Revenue Ruling 2011-11 (addressing termination issues for 403(b) plans). On request from the Council, he discussed the definition of the term “participant” under the Internal Revenue Code and noted that definitions of “employee,” “participant” and “beneficiary” vary under the tax law depending on the situation in which the term is used.

Also, on request from the Council, Mr. Bortz addressed the definition of “plan”, and clarified that the 403(b) tax rules do not prohibit a plan sponsor from dividing up benefits into multiple plans (e.g., putting the match in a different plan from the plan that holds the elective deferrals) but that there is no tax advantage to doing so as 403(b) requires an aggregation of multiple 403(b) arrangements for purposes of applying many compliance limitations and requirements. On further discussion, Mr. Bortz explained that a key purpose of the 2007 tax regulations was to clarify when a plan had been established so that employees understood their rights under the plan, including participation rights under the broad eligibility rule that is unique to 403(b) plans, the universal availability requirement.

Mr. Bortz and Ms. Edelman discussed 403(b) plan terminations and clarified that a plan is terminated when the plan sponsor adopts a resolution to terminate the plan, fully vests the participants, and notifies the participants of the plan termination. Because 403(b) plan participants with individual insurance contracts and certificates under group contracts are already in possession of the contract, in the case of a terminating plan no further actions are required in order to distribute the contracts and certificates. The rules involving insurance contracts are based on tax rules governing such distributions and apply in a similar fashion to 401(a) plans that have insurance contracts.

In response to a question about automatic enrollment for 403(b) plans, Mr. Bortz stated that automatic enrollment does not aid 403(b) plans in tax discrimination testing because the 403(b) plans use a universal availability test rather than an average benefit test. Also, he was supportive of automatic enrollment.

Mr. Bortz was asked about loans from 403(b) plans and whether there are two different types of loans with one coming from plan assets and the other type of loan coming from the insurance company and is secured by plan assets. He answered that there may be a difference in how the loan is structured, which is due to differences under state insurance law, but that there is no substantive or tax difference, and both types have been recognized as plan loans since the tax rules for plan loans were created.

In response to a question about whether smaller plans have increased difficulties or unique issues in complying with the 403(b) tax rules, Ms. Edelman responded that she had not seen that recently, especially since plan documents were implemented, and that both groups (large and small plan sponsors) tend to ask questions about the same issues (e.g., universal availability, plan termination).

Mr. Bortz was asked whether a plan sponsor, in adopting a plan document, could choose to exclude certain contracts (e.g., 90-24 transfers). He responded that the plan sponsor could for tax purposes, but that ERISA raises other considerations and requirements.

John J. (Joe) Canary, Director of the Office of Regulations and Interpretations, EBSA and

Ian Dingwall, Chief Accountant, EBSA

Mr. Canary indicated that many 403(b) plans are subject to all of the relevant requirements under Title I, while some are excluded as safe harbor plans, which are voluntarily funded solely with employee contributions and include limited involvement by the employers to facilitate the plan. Under the ERISA 403(b) safe harbor, the plan is not considered to be established and maintained by the employer for purposes of Title I. Mr. Canary noted that EBSA previously provided relief in terms of an exemption from reporting requirements for 403(b) plans (limiting reporting to filing a registration statement, not a full report with auditor’s reports and financial statements). He noted that this relief ended with the 2009 reports requirement.

The initial proposal to remove that relief was made in 2005 and finalized in 2007 followed by two years of transition and guidance (including Field Assistance Bulletins 2009-02 and 2010-01) prior to the 2009 filing requirement that placed 403(b) plans on the same reporting framework as 401(k) plans. One of the other factors that contributed to removing the filing relief was the contemporaneous IRS 403(b) regulations. With the implementation of the regulations, additional guidance was issued on how 403(b) plans could comply with the code requirements and remain safe harbor plans.

Mr. Canary stated that all of EBSA’s compliance issues tend to be facts and circumstances determinations. He indicated that there have been inquiries where there are two structures maintained by separate providers where one is deferral only and the other is limited to the employer match. He stated that DOL has provided guidance that provides that because the match was conditioned on the voluntary contribution, the voluntary contribution did not fall within the safe harbor exclusion, and consequently would cause the plan to be subject to Title I. He noted this would be the same result if the two components were included in the same plan or in separate plans. He further noted that discussions are on-going regarding plans staying in the safe harbor exclusion or recapturing safe harbor status where the plan sponsor took actions ostensibly to meet new IRS code requirements only to inadvertently fall outside of the safe harbor requirements.

Mr. Dingwall noted that 2009 was the initial year for 403(b) plans to file 5500s following an extensive education process. Because the filing requirement was new, EBSA offered some relief that it believed made it easier to comply. In terms of numbers, Mr. Dingwall stated that there were approximately 21,300 403(b) filings, where 13,000 or so were of the short form variety. Financial information on Schedule H was submitted by 8,300 filers while 6,000 filed Schedule I and approximately 600 were non-compliant in that they failed to provide any financial information. Approximately 950 filings did not attach Schedule H or Schedule I, and, as of the day prior to testimony, 300 had been corrected while approximately 600 remained that have not provided financial information. He noted that these plans are targeted for enforcement.

EBSA review technologies allowed staff to scan audit reports, looking for key words and using the outcomes of those scans to populate EBSA’s case work. The scans looked for key words found to be most effective at identifying issues. The scans showed 4,700 were essentially clean, while 81% of the filings made no reference to opening balances.

Included in the filings were 5,800 audit reports, and 5,400 of those reports that had disclaimers, mostly as the result of limited scope, while another couple hundred had disclaimers for other reasons. Otherwise, 200 audit reports included no qualifications (“unqualified”), 40 were qualified, and 5 had adverse reports on financial statements. As of this date, there were 850 annual reports that were missing accounting reports, and, 545 have since been resolved while 300 remain without the needed audit reports.

During the question and answer period, concerns were expressed concerning pre-2009 excludable contracts—where the employer had ceased to make contributions, where contracts had been distributed to former employees, or where contracts were ignored (because the plan was in the safe harbor exclusion)—only to create concerns when the plan later became an ERISA plan. EBSA representatives responded that they would not reject the Form 5500 if it was disclaimed due to these excludable contracts. They also noted the absence of guidance as to when a distribution of a contract to a participant would cause them to no longer be a plan participant. They also noted that more education and outreach is needed in the area of 403(b) plans and compliance and promised such education and outreach will be provided.

Elena Barone Chism, Associate Council, Pension Regulation for the Investment Company Institute (ICI) and

Weiyen Jonas, Vice President and Associate General Counsel of FMR LLC (Fidelity)