By Hope Hamashige

A team of researchers from the Keck School of Medicine of USC, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles (CHLA) and the USC Viterbi School of Engineering has landed a three-year, $1 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to help them develop a tiny pacemaker for unborn babies with a potentially fatal heart problem called fetal heart block.

“We needed this money to move our research forward so we’re pretty excited,” said Yaniv Bar-Cohen, associate professor of pediatrics at the Keck School and director of cardiac rhythm devices at CHLA, who is one of the principal researchers on the project.

This project got off the ground when Ramen Chmait, assistant professor of clinical obstetrics and gynecology at the Keck School, contacted Bar-Cohen to discuss fetal heart block, a condition that causes an extremely slow heart rate, which may not be adequate to sustain the circulation. They decided they wanted to build a small pacemaker and initially approached pacemaker manufacturers about collaborating with them, but they all declined due to the small initial market.

They got over that initial hurdle by searching for help at their home institution. Another colleague from USC introduced them to Gerald Loeb, a professor of biomedical engineering, who turned out to be the answer to their problem.

“We were hunting for a bioengineer and we found Dr. Loeb right here and he was the perfect fit,” said Chmait. Loeb, although a professor of engineering, is also a trained surgeon who conducts research on bionics and has extensive experience building medical devices.

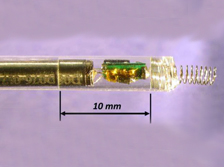

With funds from the Southern California Clinical and Translational Science Institute, the work was underway and in about five months the group had a prototype of a pacemaker that is less than 20 mm long.

This is not the first time doctors have tried to come up with a solution for fetal heart block. Others have tried using a standard pacemaker that is implanted in the mother and connected to the baby through a wire. But because babies in the womb do wriggle, the wires become dislodged and the baby dies.

To avoid that problem, the USC group—which also includes Michael Silka, Keck School professor and director of cardiology at CHLA, and Jay Pruetz, assistant professor of pediatrics at the Keck School and director of fetal cardiology at CHLA—has designed a pacemaker that is implanted directly onto the baby’s heart using a cannula similar to a narrow straw. In other words, it will not have externalized wires that the baby can dislodge and placing it on the baby will not require invasive surgery.

Chmait, who is also director of Los Angeles Fetal Therapy, called the award a “very pleasant surprise” explaining that the USC group was a little unsure of their chances since the NIH tends to fund research that will benefit large numbers of people. This device, if it eventually works, will likely only be implanted into a few hundred babies every year.

Bar-Cohen added, however, that there may eventually be a broader use for a pacemaker similar to this one. The hope is that eventually this device, or something similar that does not require invasive surgery to implant, will eventually be used in children and adults, not only fetuses.

Both Chmait and Bar-Cohen said they are optimistic that they will be able to begin testing the device soon and that the NIH grant could help them see this project through.

“I strongly believe that we will have something in three years,” said Chmait.