A Look Inside Dawn’s Grand Asteroid Adventure

Wednesday, February 1st, 2012

As NASA’s Dawn spacecraft investigates its first target, the giant asteroid Vesta, Marc Rayman, Dawn’s chief engineer, shares a monthly update on the mission’s progress.

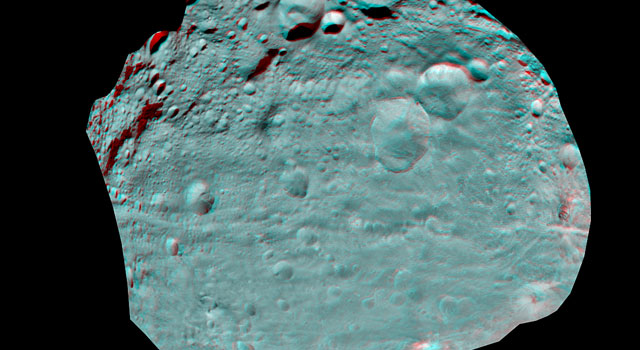

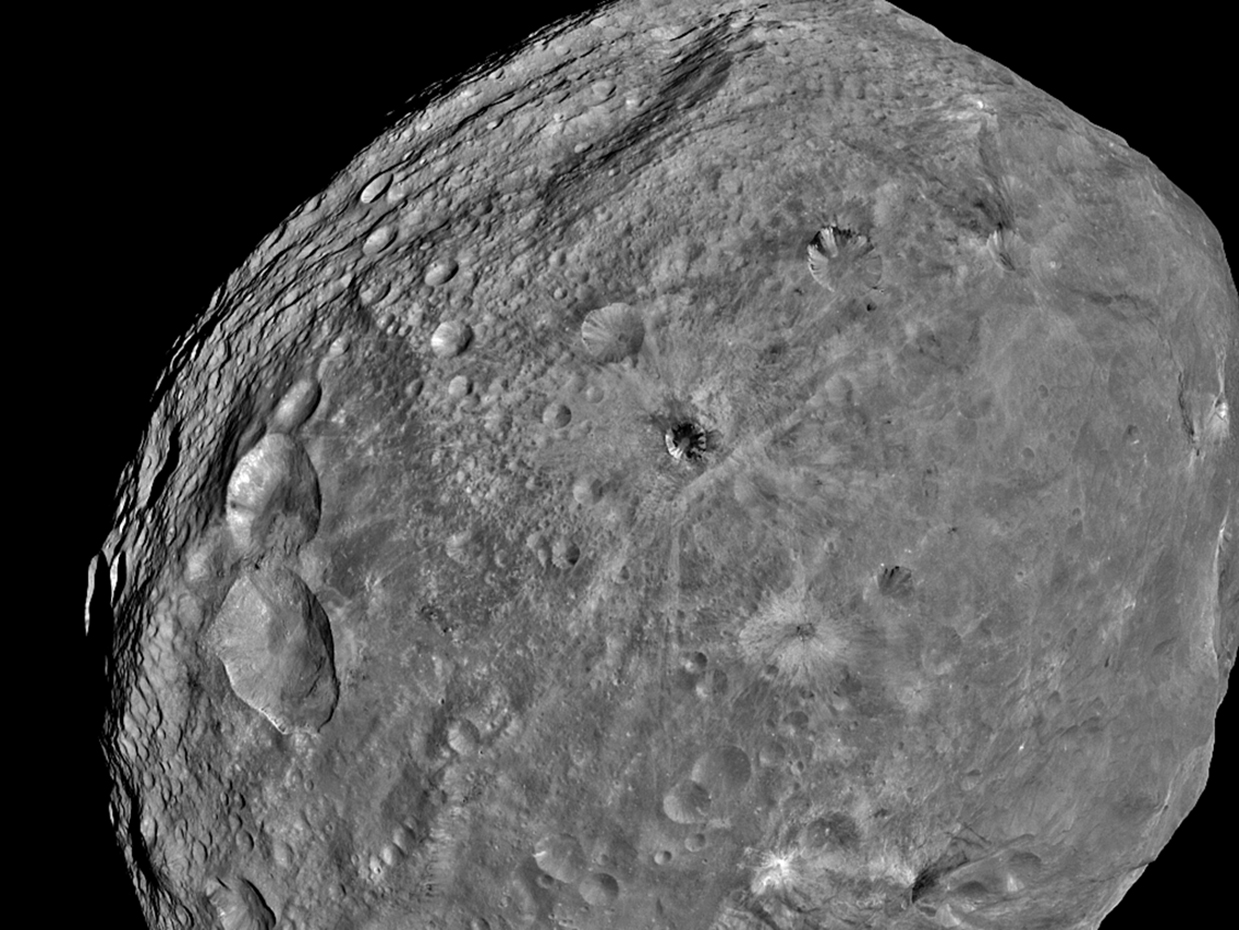

The south pole of the giant asteroid Vesta, as imaged by the framing camera on NASA’s Dawn spacecraft in September 2011. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA |

› Full image and caption

Dear Asdawnished Readers,

Dawn is scrutinizing Vesta from its low-altitude mapping orbit (LAMO), circling the rocky world five and a half times a day. The spacecraft is healthy and continuing its intensive campaign to reveal the astonishing nature of this body in the mysterious depths of the main asteroid belt.

Since the last log, the robotic explorer has devoted most of its time to its two primary scientific objectives in this phase of the mission. With its gamma ray and neutron detector (GRaND), it has been patiently measuring Vesta’s very faint nuclear emanations. These signals reveal the atomic constituents of the material near the surface. Dawn also broadcasts a radio beacon with which navigators on distant Earth can track its orbital motion with exquisite accuracy. That allows them to measure Vesta’s gravity field and thereby infer the interior structure of this complex world. In addition to these top priorities, the spacecraft is using its camera and its visible and infrared mapping spectrometer (VIR) to obtain more detailed views than they could in the higher orbits.

As we have delved into these activities in detail in past logs, let’s consider here some more aspects of controlling this extremely remote probe as it peers down at the exotic colossus 210 kilometers (130 miles) beneath it.

Well, the first aspect that is worth noting is that it is incredibly cool! Continuing to bring this fascinating extraterrestrial orb into sharper focus is thrilling, and everyone who is moved by humankind’s bold efforts to reach into the cosmos shares in the experience. As a reminder, you can see the extraordinary sights Dawn has by going here for a new image every weekday, each revealing another intriguing aspect of the diverse landscape.

The data sent back are providing exciting and important new insights into Vesta, and those findings will continue to be announced in press releases. Therefore, we will turn our attention to a second aspect of operating in LAMO. Last month, we saw that various forces contribute to Dawn moving slightly off its planned orbital path. (That material may be worth reviewing, either to enhance appreciation of what follows or as an efficacious soporific, should the need for one ever arise.) Now let’s investigate some of the consequences. This will involve a few more technical points than most logs, but each will be explained, and together they will help illustrate one of the multitudinous complexities that must be overcome to make such a grand adventure successful.