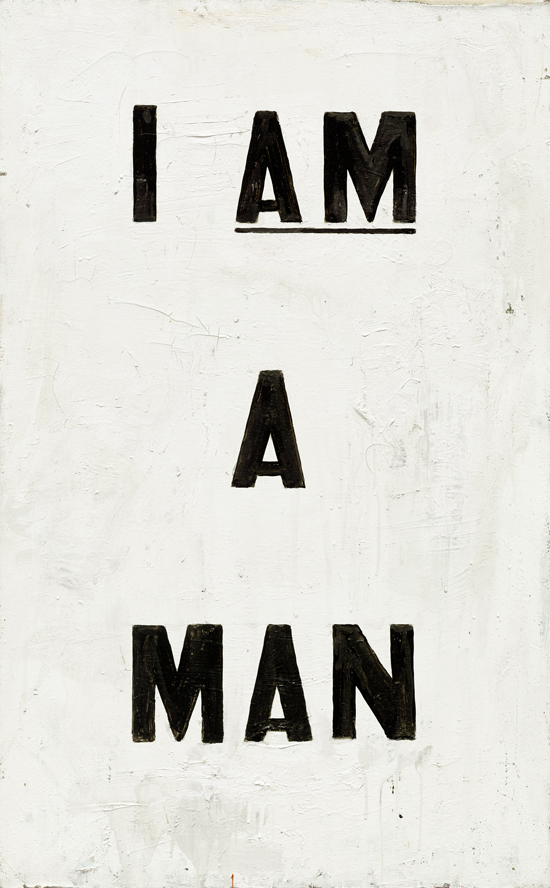

Glenn Ligon, Untitled (I Am a Man), 1988

Glenn Ligon, Untitled (I Am a Man), 1988

Glenn Ligon was born in the Bronx in 1960, attended the Walden School in New York on a scholarship, and graduated from Wesleyan University in 1982. He participated in the Whitney Museum's Independent Study Program in 1985, known at that time for its language-based approach. Ligon is best known for intertextual works that re-present American history and literature, in particular narratives of slavery and civil rights, for contemporary audiences. His work engages a powerful mix of racial and gender-oriented struggles for the self, leading viewers to reconsider problems inherent in representation.

Untitled (I Am a Man) is just such a representation—a signifier—of the actual signs carried by 1,300 striking African American sanitation workers in Memphis, made famous in Ernest Withers' 1968 photographs. Prompted by the wrongful deaths of two coworkers from faulty equipment, the strikers marched to protest low wages and unsafe working conditions. They took up the slogan "I Am a Man" as a variant on the first line of Ralph Ellison's prologue to Invisible Man, "I am an invisible man." By deleting the word "invisible," the Memphis strikers asserted their presence, making themselves visible in standing up for their rights. Martin Luther King Jr. traveled to Memphis to address the striking workers; the next day, he was assassinated.

This painting is Ligon's most important and iconic work. As the first object in which he used a selected text, Untitled (I Am a Man) is his breakthrough. He took pains to differentiate the painting from the original signs, avoiding a one-to-one relationship by reorganizing the line breaks. And while he preserved the original black-on-white of the sign, his choice to paint the black letters in eye-catching enamel calls attention to a black figure ("Man") as a text that replaces the human form in figurative painting. Throughout his career, Ligon has used "blackness" as a trope for both personal and collective experience. As Ligon has said (paraphrasing Muhammed Ali), "It's not about me. It's about we." The deliberately rough surface of the painting, which Ligon later documented by having a condition report made as an ancillary work of art, seems to index the scars and struggles of the work's great subject.

Untitled (I Am a Man) is the Gallery's first painting by Ligon and complements a suite of etchings and a print portfolio.

Glenn Ligon, Untitled (I Am a Man), 1988, oil and enamel on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, 101.6 × 63.5 cm (40 × 25 in.), Patrons' Permanent Fund and Gift of the Artist, © Glenn Ligon

Robert Adams, American, born 1937, Kerstin enjoying the wind. East of Keota, Colorado, 1969

Robert Adams, American, born 1937, Kerstin enjoying the wind. East of Keota, Colorado, 1969

For more than 40 years, the distinguished photographer Robert Adams has recorded the changing American landscape, revealing both its sublime beauty and its wanton destruction. Like his 19th-century predecessors, such as Timothy O'Sullivan, he has chronicled the ongoing settlement of the American West, especially Colorado, California, Oregon, and Washington. Yet unlike those earlier photographers, he has recorded the freeways, strip malls, parking lots, billboards, and tract houses that have utterly transformed the landscape in the last 50 years, as well as the abandoned orange groves of Southern California and the despoiled forests of the Northwest. In addition, he has turned his camera on the citizens of this New West, photographing young children who grew up in the shadow of nuclear weapons plants, as well as parents and grandparents who were often isolated from one another and nature itself by the very modern conveniences they coveted.

Yet Adams' work is no diatribe and often records the beauty that remains—indeed, refuses to die—in the magnificent light of the high plains, for example, or the graceful form of the earth itself. He is convinced, as he wrote in 1974, that "all land, no matter what has happened to it, has over it a grace, an absolutely persistent beauty." Combining hope and despair, joy and grief, his lucid but passionate photographs are profound and provocative records of this time and place.

Born in New Jersey, raised in Wisconsin and Colorado, Adams received a PhD in English literature and turned to photography in 1963, at the age of 26. With encouragement from the renowned curator John Szarkowski, Adams abandoned his career as an English professor in 1970 and devoted himself to photography. A gifted writer with a deep fascination for books of photographs, Adams first achieved acclaim in 1974 with the publication of The New West: Landscapes along the Colorado Front Range, one of the first books of photographs to present a more critical view of the American West. This book was soon followed by 15 more, most recently Questions for an Overcast Day (2009). In addition to numerous exhibitions at major museums around the world, Adams has been honored with many awards, including two Guggenheim Fellowships, the Hasselblad Award for Distinguished Photographer, and a MacArthur Foundation fellowship.

Recently, the Gallery acquired 169 photographs by Adams. This collection is truly exceptional and unique, for the artist himself carefully selected it to complement the 25 works by him already in the Gallery's collection. Together they represent what he considers to be his most important accomplishments. The new acquisition includes key photographs from each of his 16 books, as well as 16 other photographs from throughout his career. A modest man with deeply held convictions, Adams believes "these photographs can tell Americans something they might want to know about their country."

Robert Adams, American, born 1937, Kerstin enjoying the wind. East of Keota, Colorado, 1969, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Pepita Milmore Memorial Fund and Gift of Robert and Kerstin Adams

Bertel Thorvaldsen, Possibly Lady Louisa Bingham, model 1816 and/or 1817/1818, carved c. 1821/1824

Bertel Thorvaldsen, Possibly Lady Louisa Bingham, model 1816 and/or 1817/1818, carved c. 1821/1824

The acquisition of three exquisite marble busts from the early 19th century, Three Daughters of Richard Bingham, Lord Lucan, brings the name of the renowned Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen, one of the handful of truly great neoclassical artists, into the Gallery's collection for the first time. The sculptures are portraits of daughters of one of Thorvaldsen's most important patrons, Richard Bingham, second Earl of Lucan.

Thorvaldsen was the son of a woodcarver of Icelandic origin. He entered the Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen at the precocious age of eleven. In 1797, he won a stipend to study in Rome, where the cultural landscape was then dominated by Antonio Canova (1757–1822), the most famous living artist in Europe. No sculptor at that time escaped Canova's influence, and Thorvaldsen's early concept for a gigantic, classicizing plaster statue of the mythical hero Jason showed that he could not resist Canova's magic either. Canova's partisans, who were largely French and Italian, promoted the misty sensuality of the Italian sculptor's art. Thorvaldsen's defenders, who were primarily German and Scandinavian, instead would praise the Danish artist's frankness and reticent naturalism.

In 1803, Thomas Hope, the eminent British collector of classical antiquities, commissioned the colossal Jason in marble, enabling the otherwise penniless Thorvaldsen to remain in Rome. The Dane's subsequent success is demonstrated by numerous commissions for huge equestrian and funerary monuments, as well as the Lion of Lucerne for a Swiss mountainside and architectural reliefs for the Quirinal Palace in Rome, Christiansborg Palace in Copenhagen, and the Villa Carlotta near Lugano. Thorvaldsen established his own museum in his native Copenhagen—the first public museum in Denmark. Most of his plaster models, dozens of drawings, marble sculptures, his collection of antiquities and paintings, and his archive are preserved there.

Lord Lucan commissioned the first marble examples of Thorvaldsen's reliefs Night and Day, which were replicated in more than a dozen examples during Thorvaldsen's lifetime. Lord Lucan also ordered the first marble example of Thorvaldsen's Triumphant Venus, and he bought the Standing Baptismal Angel, originally created for the Church of Our Lady in Copenhagen (now in the Nationalmuseum, Stockholm).

Although Lord Lucan was said to have considered commissioning portraits of his wife and three of his four daughters, Thorvaldsen's account books list only the busts of the "older (la maggiore) Lady Lucan" and the "younger (la minore) Lady Lucan." A third bust, recorded as "Madame Vernot" and perhaps ordered separately, must portray Bingham's eldest daughter Elizabeth, whose married name was Vernon. The plaster model for it and for another bust that corresponds to the marble one identified here as Louisa Bingham Elcho are both in the collection in Thorvaldsens Museum. The busts apparently remained with the Bingham family for more than a century: when they appeared at auction in 1999, the seller attested that his father had bought them from Lord Lucan in the 1960s, which is when, coincidentally, the seventh earl succeeded to the title.

Bertel Thorvaldsen, Danish, 1770–1844, Possibly Lady Louisa Bingham, model 1816 and/or 1817/1818, carved c. 1821/1824, marble overall (including integral socle): 58.42 x 28.89 x 22.23 cm (23 x 11 3/8 x 8 3/4 in.), Patrons' Permanent Fund, 2011.101.2

Born in Bia, Hungary, in 1922, Simon Hantaï settled in France in 1948 and joined the surrealist circle of André Breton. After experimenting with a variety of painting techniques in the 1950s, he saw Jackson Pollock's work, which offered a way to push beyond both surrealist automatism and European gesturalism. Inspired by Pollock's pouring of paint onto horizontal canvases—leaving behind self-conscious style for a physical engagement with the medium—in 1960 Hantaï invented a method of pliage (folding) that defined the rest of his career.

With many variations over the course of five decades, Hantaï's pliage entailed applying paint to bunched or knotted canvas and then stretching the canvas to produce a traditional rectangular painting, but one marked by a lack of visual control verging on blindness. "Through folding I put my eyes out," he reflected in 1997, referring to a childhood episode of temporary blindness induced by diphtheria and also evoking Pollock's radical repositioning of the artist "in" the painting rather than at a comfortable distance from it.

In Hantaï's first paintings using this method, he obsessively filled the canvas, following Pollock's all-over structure. Then, in the Meun series of 1967–1968, he allowed the white of the primed canvas to penetrate and define his monochromatic forms. With this step, inspired by the cut-outs of Henri Matisse, Hantaï achieved what he called "the unpainted made active," something he pursued ever further for the rest of his career.

Étude is an early example from Hantaï's next and arguably most important series: the Études (1968–1972). Here the artist has combined the all-over structure of his first pliages with the use of reserved canvas in the Meun series. He has multiplied the number of knots and reduced their scale, producing a dense pattern that is at once fractured and sublimely decorative. The lyrical suggestion of birds or foliage is held in check by the aggressive red color and the violent intervention of the primed canvas, the "unpainted paint." Viewers are dazzled as they attempt to decide whether the white areas (which are deliberately given as much of the surface as the red) constitute figure or ground. Photograms come to mind, with their direct production of silhouetted images by blocking or admitting the passage of light onto sensitive paper.

Through his experimentation, Hantaï developed a unique way of maintaining beauty while acknowledging the radical skepticism about authorship, control, and self-expression that has characterized painting after Pollock. Hantaï was a major figure in France, inspiring the Supports/Surfaces group in particular. The Gallery has three drawings by the artist from the Rosenwald Collection; this first painting by Hantaï greatly strengthens the collection of postwar European art.

Simon Hantaï, French, born Hungary, 1922–2008, Étude, 1969, oil on canvas, overall: 275 x 238 cm (108 1/4 x 93 11/16 in.), Gift of the Collectors Committee, © 2012 Estate Simon Hantaï, 2012.20.1

Robert Seldon Duncanson, American, 1821–1872, Still Life with Fruit and Nuts, 1848

Robert Seldon Duncanson, American, 1821–1872, Still Life with Fruit and Nuts, 1848

African American artist Robert Seldon Duncanson (1821–1872) was widely recognized during his lifetime for pastoral landscapes of American, Canadian, and European scenery. Recent scholarship, however, has begun to focus on a small group of still-life paintings (fewer than a dozen are known) that Duncanson produced during the late 1840s. Spare, elegant, and meticulously painted, these works reflect the tradition of American still-life painting initiated by Charles Willson Peale and his gifted children—particularly Raphaelle and Rembrandt Peale. Still-life paintings by Duncanson are extremely rare and highly coveted. Signed and dated 1848, Still Life with Fruit and Nuts is a particularly fine example and the first work by Duncanson to enter the Gallery's collection. Classically composed with fruit arranged in a tabletop pyramid, the painting includes remarkable passages juxtaposing the smooth surfaces of beautifully rendered apples with the textured shells of scattered nuts.

Self-taught and living in Cincinnati when he created his still-life paintings, Duncanson exhibited several of these works at the annual Michigan State Fair. During one such exhibition, a critic for the Detroit Free Press wrote, "the paintings of fruit, etc. by Duncanson are beautiful, and as they deserve, have elicited universal admiration." The artist's turn from still-life subjects to landscapes conveying religious and moral messages may have been inspired by the exhibition in Cincinnati of Thomas Cole's celebrated series The Voyage of Life. Cole's allegorical paintings were purchased by a private collector in Cincinnati and remained in that city until acquired by the National Gallery of Art in 1971. Exposure to Cole's paintings marked a turning point in Duncanson's career. Soon he began creating landscapes that incorporated signature elements from Cole and often carried moral messages.

Following the outbreak of the Civil War, Duncanson traveled to Canada, where he remained until departing for Europe in 1865. Often described as the first African American artist to achieve an international reputation, Duncanson enjoyed considerable success exhibiting his landscapes abroad. His achievement as a still-life painter has only recently become apparent. The exceptional quality of Still Life with Fruit and Nuts suggests that much remains to be learned about this little-known aspect of his career.

Thanks to the generosity of Ann and Mark Kington/The Kington Foundation and the Avalon Fund, Duncanson's masterful still-life painting hangs in the American galleries not far from Cole's Voyage of Life.

Robert Seldon Duncanson, American, 1821–1872, Still Life with Fruit and Nuts, 1848, oil on board, overall: 30.48 x 40.64 cm (12 x 16 in.), Gift of Ann and Mark Kington/The Kington Foundation and the Avalon Fund, 2011.98.1

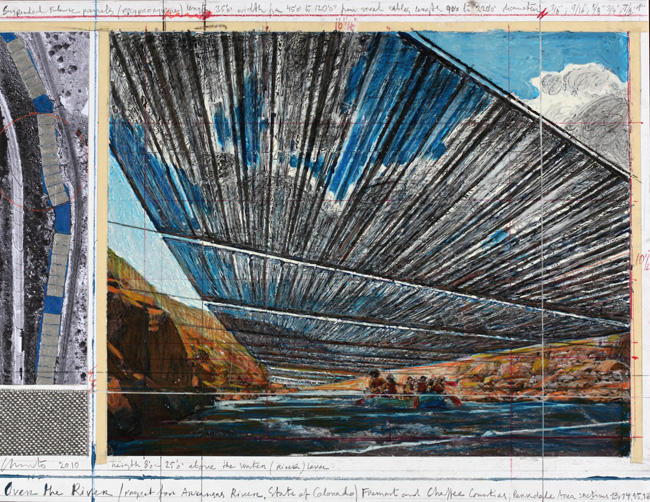

Christo, American, born Bulgaria, 1935, Over the River (Project for Arkansas River, State of Colorado), 2010, Gift of the artist.

Christo, American, born Bulgaria, 1935, Over the River (Project for Arkansas River, State of Colorado), 2010, Gift of the artist.

For a half-century, Christo and his late wife and collaborator Jeanne-Claude have created large-scale, temporary works of art in both urban and rural environments. These projects have challenged the traditional definitions of sculpture and artistic practice while creating a new discourse for issues concerning the environment and aesthetics. From early wrapped objects to monumental outdoor projects including Running Fence (1972–1976), Wrapped Reichstag, Berlin (1971–1995), and The Gates, Central Park, New York City (1979–2005), the artists have used fabric—wrapped, draped, and folded over, around, and through natural and constructed forms—to transcend the traditional bounds of painting, drawing, sculpture, and architecture.

On November 8, 2011, Christo presented the National Gallery of Art with two original preparatory collages for Over The River, Project for the Arkansas River, Colorado, both dating from 2010, for the Gallery's permanent collection. The gifts were unveiled during a press conference with Secretary of the Interior Kenneth Salazar, a day after the Department of the Interior's Bureau of Land Management officially approved Over The River, a project that Christo developed with Jeanne-Claude. The gift, alongside the Gallery's existing collection of preparatory works on paper from various stages of this project—two early drawings from 1992 and two large collages from 2000—illustrates Christo and Jeanne-Claude's working process and brings to light the project's development as it has evolved over the past two decades.

Over The River is a temporary art installation first proposed in 1992 by Christo and Jeanne-Claude. For this work, Christo will suspend 5.9 miles of silvery fabric panels high above the Arkansas River interstitially along a 42-mile stretch between Salida and Cañon City in Colorado. Fabric panels will be suspended at eight distinct areas of the river that were selected by the artists for their aesthetic merits and technical viability. The fabric, suspended ten to twenty-three feet above the river, will be translucent when seen from below, affording rafters and kayakers a view of the sky. However, when seen from above, from trails and the highway that parallel the Arkansas River, the panels will appear opaque. Through its intermittent installation, Over The River will seem to materialize and dematerialize, prefiguring the project's temporary nature. If the permit process moves forward as planned, Christo hopes to present Over The River for two consecutive weeks in August 2014. Information about the project is located at www.OverTheRiverInfo.com.

Christo, American, born Bulgaria, 1935, Over the River (Project for Arkansas River, State of Colorado), 2010, collage, overall: 42.2 x 55.9 cm (17 x 22 in.), Gift of the artist © Christo 2010

John Storrs, American, 1885–1956, Auto Tower, Industrial Forms (part B), c. 1922, Gift of Deborah and Ed Shein

John Storrs, American, 1885–1956, Auto Tower, Industrial Forms (part B), c. 1922, Gift of Deborah and Ed Shein

A pioneering figure in the development of American modernist sculpture, John Storrs incorporated the lessons of cubism and futurism and the streamlined design elements of industrialism to create some of the first abstract sculptures in the United States. Storrs was born in Chicago in 1885 and studied art in Hamburg, Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia, and Paris, under such noted sculptors as Arthur Bock and Auguste Rodin. He traveled extensively through Europe, North Africa, Canada, and Mexico, and he was deeply affected by such disparate styles as the art of the Vienna Secession, ancient Greek and Egyptian art, and Southwest and Pacific Northwest Indian art. The son of an architect and real estate developer, Storrs also had a lifelong interest in the interrelationship of sculpture and architecture, and he maintained close friendships with such Chicago architects as Louis Sullivan, John Root, and Frank Lloyd Wright. In the early-to-mid-1920s, Storrs began to make architectonic "column-tower" sculptures, which were inspired by modern New York skyscrapers, as well as by classical art and American Indian designs.

This gift, Auto Tower, Industrial Forms (part B), is one of a pair of large painted cast-concrete sculptures that Storrs may have been commissioned to produce for an estate in Gland, Switzerland, perhaps at the behest of the renowned art deco design firm, Maison Jansen. The pieces are related to a number of much smaller works: the bronze Auto Tower (Industrial Forms), c. 1922 (location unknown); a plaster model for the bronze, c. 1922 (location unknown); a painted plaster version of the sculpture, c. 1922 (Smith Collection); and a pen and ink drawing, Study for Auto Tower (Industrial Forms), 1920 (Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Alvin S. Lane). The plaster model for the bronze Auto Tower was shown in Storrs' 1923 one-artist exhibition at the Société Anonyme in New York, which established him as a member of the international avant-garde. The plaster for the bronze was also reproduced in the winter 1922 edition of The Little Review, along with an essay by Storrs titled "Museums or Artists," in which Storrs expressed his belief that modern sculpture should be created directly for architecture.

Despite the cool abstraction of much of his work, there is a playful side to Storrs' sculpture. Auto Tower, Industrial Forms (parts A and B) reflect the Dada and surrealist humor of the "geste," or visual pun, that was current in avant-garde circles in the 1920s. When turned horizontally, the sculptures are transformed from skyscraper tower forms into sleek automobiles. The pieces also have distinctly anthropomorphic qualities—the related ink drawing of the bronze shows that Storrs intended the works to be viewed as the profile of totemic figures.

Auto Tower, Industrial Form (parts (parts A and B) stand alone as an important example of Storrs' architectonic sculpture from the early 1920s. These gifts greatly strengthen our collection of American modernist sculptures by artists such as John Flannagan and Alexander Calder. Furthermore, the sculptures complement our holdings of European avant-garde sculpture by artists such as Constantin Brancusi, Jean Arp, and Jacques Lipchitz. They are the first sculptures by Storrs to enter the Gallery's collection.

John Storrs, American, 1885–1956, Auto Tower, Industrial Forms (part B), c. 1922, cast and painted concrete, height: 152.4 cm (60 in.) maximum width: 25.4 cm (10 in.) depth: 30.48 cm (12 in.), Gift of Deborah and Ed Shein, 2011.1.1

Nancy Graves, Agualine, 1980, Collection of Robert and Jane Meyerhoff

Nancy Graves, Agualine, 1980, Collection of Robert and Jane Meyerhoff

Throughout her career, Nancy Graves mined the world of natural science for her imagery, from meticulously constructed camels to detailed cartographic studies. Her dual interest in science and art started with childhood visits to the Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, where her father worked and which housed a combined collection of art and natural history. In the late 1970s, Graves became interested in archaeology. She was awarded a residency at the American Academy in Rome in 1979 and used the opportunity to tour ancient sites throughout the Mediterranean. The excavations she visited illustrated for Graves how cultures become layered over time, each new civilization consuming the previous one. The complex layering and fragmenting of color, form, line, and technique in Agualine, painted in 1980 once she had returned to New York, speak to the palimpsest of history.

Agualine builds on a lexicon of images that Graves developed through the 1970s but pushes those literal references to the very edge of abstraction. Compositionally, Agualine is reminiscent of her painting Scaux, 1977, and her print Paleolinea, 1982, but begun in 1979, two works that reproduce the linear patterns from an Upper Paleolithic cave drawing in Altamira, Spain. In Agualine, the brown and black lines dancing across the canvas borrow from the same source but lack the fidelity of transcription.The band of thickly applied orange brushstrokes across the lower right corner of the canvas recalls a type of carved bone or horn found at Upper Paleolithic sites, although again it is less faithfully rendered in Agualine than in Scaux or Paleolinea. Agualine is also distinct from the gray Scaux in its high-keyed palette, signaling the brightly colored patinas Graves would use in her sculpture of the 1980s, including the National Gallery's Spinner, 1985, gift of Lila Acheson Wallace. Despite these overt references to caves, the title Agualine has a distinctly nautical sound. A compound of the words "agua" (Spanish for water) and "line," this invented term may best be described as a poetic abstraction that calls to mind Roman aqueducts or perhaps the frenetic movement of underwater life. The fluidity of the paint handling and the variety of marks suggest the tracks of sea creatures moving across the ocean floor and recall her bathymetric paintings of the early 1970s. Agualine, with its gestural exuberance, loud color, and dispersed composition, can be seen as a contemporary successor to the National Gallery's great painting by Wassily Kandinsky, Improvisation 31 (Sea Battle), 1913, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund. Agualine was generously donated by Robert E. Meyerhoff. It is the first painting by Graves to enter the collection and joins five sculptures, eleven drawings, and one print by the artist.

Nancy Graves, American, 1940–1995, Agualine, 1980, oil on canvas, overall: 111.8 x 167.6 cm (44 x 66 in.), Collection of Robert and Jane Meyerhoff, 2010.14.1

Cornelis Verbeeck, A Naval Encounter between Dutch and Spanish Warships, c. 1618/1620, Gift of Dorothea V. Hammond

Cornelis Verbeeck, A Naval Encounter between Dutch and Spanish Warships, c. 1618/1620, Gift of Dorothea V. Hammond

In 1995 two marine paintings, Dutch Warship Attacking a Spanish Galley and Spanish Galleon Firing its Cannons were bequeathed to the National Gallery of Art. Technical examinations determined that the two panels originally had formed a single painting that was subsequently cut in half to form two separate works. Dendrochronological analysis revealed that the two horizontally-joined oak panel boards from each segment came from the same two trees. This technical information coupled with compositional evidence, such as corresponding cloud and wave patterns on the two segments, demonstrated that the two panels had once formed a continuous larger composition with the Spanish Galleon Firing its Cannons panel on the left and the Dutch Warship Attacking a Spanish Galley panel on the right. Fortunately, the two panels had remained together throughout their history, and after they were conserved in 2009-2010 they were brought together to recreate the original appearance of Verbeeck's work.

This reconstructed painting vividly depicts an intense naval engagement, characteristic of Dutch battles against Spain during the long Dutch Revolt. At right, a Dutch warship under full sail has attacked a small Spanish galley that is sinking in the stormy sea. The Dutch ship is alive with triumphant activity, from the commander and trumpeter standing on the poop deck beneath the red flag, to the sailors scurrying up the rigging and the soldiers reloading their muskets. At left, a Spanish galleon is firing its portside cannons towards the large Dutch warship while trying to hit another Dutch ship with its starboard cannons. The smaller Dutch vessel has already reduced a Spanish galley to a burning wreck. Verbeeck's painting, which the artist signed Cornelis VB on the red, white, and blue Dutch flag atop the main mast, does not appear to represent an actual battle scene but seems to be a nautical metaphor celebrating the victory of the Dutch people over their enemy.

Verbeeck's Battle: Restoring War in the Conservation Lab At the time of their acquisition in 1995, Cornelis Verbeeck's paintings Dutch Warship Attacking a Spanish Galley and Spanish Galleon Firing Its Cannons were covered with layers of discolored varnish. Their sojourn in the conservation lab, however, revealed a complex story that transformed our understanding of these paintings. Arthur Wheelock, curator of northern baroque paintings, is joined by Michael Swicklik, senior conservator, and Richard Ford, frame conservator, as they discuss this exciting discovery, and the paintings' new appearance as two halves of a reunited battle scene.

At the time of their acquisition in 1995, Cornelis Verbeeck's paintings Dutch Warship Attacking a Spanish Galley and Spanish Galleon Firing Its Cannons were covered with layers of discolored varnish. Their sojourn in the conservation lab, however, revealed a complex story that transformed our understanding of these paintings. Arthur Wheelock, curator of northern baroque paintings, is joined by Michael Swicklik, senior conservator, and Richard Ford, frame conservator, as they discuss this exciting discovery, and the paintings' new appearance as two halves of a reunited battle scene.

Watch | iTunes | Watch on ArtBabble | RSS (4:48 mins.)

Cornelis Verbeeck, Dutch, c. 1590/1591–c. 1637, A Naval Encounter between Dutch and Spanish Warships, c. 1618/1620, oil on panel, Gift of Dorothea V. Hammond

Martin Johnson Heade, Sunlight and Shadow: The Newbury Marshes, c. 1871/1875, John Wilmerding Collection

Martin Johnson Heade, Sunlight and Shadow: The Newbury Marshes, c. 1871/1875, John Wilmerding Collection

The first pictures of marshlands by Martin Johnson Heade featured the environs of Newbury and Newburyport, Massachusetts, near the mouth of the Merrimack River. Perhaps attracted by John Greenleaf Whittier's poetry that celebrated the local landscape or more likely drawn there by his acquaintance with Bishop Thomas March Clark of Newburyport, Heade discovered the area sometime around 1859. By the end of his career he had executed more than 100 marsh subjects, a body of work that accounts for almost one-fifth of his entire known oeuvre as a painter. Over the course of this series Heade captured the essential character of the wetlands environment. He depicted the tides, meteorological phenomena, and other natural forces that shaped the appearance of the swamp and showed how the land was used for hunting, fishing, and the harvesting of naturally occurring salt hay. No other artist of the era explored and analyzed the unique qualities of the marshes in such a sustained and detailed way.

Sunlight and Shadow is a particularly masterful example of how Heade balanced many countervailing forces in his wetland compositions. The serpentine line of the tidal creek receding into the open plain on the right is offset by the visual weight of the haystack and apple tree on the left. The rhythm of the creek's movement is complemented by the undulating wave pattern that the treetops and clouds trace across the sky. The pink clouds are mirrored in the shallow pool of water at the lower center of the painting, and the form of the tree leaning left is echoed in the sweep of the high thin clouds placed in the upper right corner. Finally, the painting's primary motif, sunlight and shadow, seen, for instance, in its intricate cloud shadows and the subtle movement from light to dark across the body of the haystack, informs and unites all its visual elements.

Sunlight and Shadow: The Newbury Marshes is the latest gift to the Gallery from the John Wilmerding Collection. It joins other masterworks by Heade from the Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation, Cattleya Orchid and Three Hummingbirds, and The Circle, Giant Magnolias on a Blue Velvet Cloth. The Gallery's permanent collection now includes a remarkable example of each of the three distinctive subjects that defined Heade's singular career—hummingbirds, flowers, and marshes.

Martin Johnson Heade, American, 1819–1904, Sunlight and Shadow: The Newbury Marshes, c. 1871/1875, oil on canvas, overall: 30.5 x 67.3 cm (12 x 26 1/2 in.), John Wilmerding Collection, 2010.74.1

Anne Truitt, Knight's Heritage, 1963, Gift of the Collectors Committee

Anne Truitt, Knight's Heritage, 1963, Gift of the Collectors Committee

Although often connected to minimalist sculptors such as Donald Judd, who also made simple painted wooden objects at roughly the same time, Anne Truitt had little in common with the anti-aesthetic and anti-compositional stance of that loosely defined movement. Rather, her epiphany came in 1961, when she first saw in person the paintings and sculptures of Barnett Newman and Ad Reinhardt. Like Newman, Truitt was committed to the expressive value of carefully chosen color and to the significance of compositional decisions regarding the division of the rectangle.

Both qualities are evident in Knight's Heritage, an important transitional piece in which Truitt still employed a brushy texture to define the paint surface and actual grooves to mark the three divisions (elements she abandoned in her later, smoother work) but began to break out of the somber tones of her earliest work and embrace glowing color. The title has several possible references, including the popular 19th-century medieval fictions of Howard Pyle, which Truitt enjoyed, and the Kennedy administration ("Camelot"), which she admired and to which she had social connections. The simple frontal array of the work has a heraldic aspect that reinforces these associations.

Born in Baltimore in 1921 and raised on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, Truitt settled in Washington, DC, in 1948 and remained in the region until her death in 2004. While the Gallery's collection includes two of her towering columnar works and one small horizontal piece from the 1970s, the addition of this major work from her breakthrough years establishes a more complete representation of this influential American sculptor's career.

Anne Truitt, Knight's Heritage, 1963, acrylic on wood, 153.35 x 153.35 x 30.48 cm (60 3/8 x 60 3/8 x 12 in.), Gift of the Collectors Committee, 2011

Kerry James Marshall, Great America, 1994, acrylic and collage on canvas, Gift of the Collectors Committee

Kerry James Marshall, Great America, 1994, acrylic and collage on canvas, Gift of the Collectors Committee

Great America (1994) by Kerry James Marshall is the Gallery's first painting by this major midcareer artist. A devoted student of the human figure and the history of art, Marshall draws upon the experience of African Americans to create imposing, contemporary history paintings.

Marshall's mature career can be dated to 1980, when, inspired by the opening lines of Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man, he developed his signature motif of a dark, near-silhouetted figure in A Portrait of the Artist as His Former Self. Refusing both negative and positive stereotypes of black people, Marshall's figures of "extreme blackness" operate, he explains, "right on the borderline," forcing the viewer to find nuance and articulation within only apparently black forms. This strategy has been influential for younger artists, including Kara Walker and Glenn Ligon.

Great America is contemporaneous with Marshall's well-known Garden Project (1994–1995), a series of paintings based on housing projects with "gardens" in their names, such as Nickerson Gardens in Watts, where he grew up. In those works, Marshall sought to convey the dignity and complexity of lives set within difficult circumstances. In Great America he re-imagines a boat ride into the haunted tunnel of an amusement park as the Middle Passage of slaves from Africa to the New World. What might in other hands be a work of heavy irony becomes instead a delicate interweaving of the histories of painting and race. The painting, which is stretched directly onto the wall, creates a screen or backdrop onto which viewers project their own associations triggered by the diaphanous yet powerful imagery.

Born in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1955, Marshall grew up in Los Angeles and graduated from Otis Art Institute. After spending time as a fellow at the Studio Museum in Harlem, he moved to Chicago in 1987, where he still lives and works.

Kerry James Marshall, American, b. 1955, Great America, 1994, acrylic and collage on canvas, overall: 261.62 x 289.56 cm (103 x 114 in.), Gift of the Collectors Committee

Jenny Holzer, DODDOACID, 2007, Gift of the Artist, © Jenny Holzer

Jenny Holzer, DODDOACID, 2007, Gift of the Artist, © Jenny Holzer

Throughout her career, Jenny Holzer has engaged the public consciousness through her text-based art. Beginning in 1977 with Truisms, a series of witty and salient aphorisms posted in public spaces, Holzer has never shied away from sensitive material. She has mined declassified U.S. government documents for the series Redaction Paintings meticulously silk-screened works that depict blacked-out handprints of American soldiers accused of committing crimes in Iraq.

The idea for the Redaction Paintings came in 2004 when Wired magazine asked Holzer to imagine a new landing page for Google's search engine. "I wanted to see secrets," she remembered, "a different secret every time I logged on." She went looking and found a letter on thesmokinggun.com in which Enron founder Kenneth Lay thanked the then governor of Texas George W. Bush for a gift of art. Searching more widely, she trawled the websites of the National Security Archive, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), and the Federal Bureau of Investigation. She focused on documents about the Middle East, and when she found something of interest, she painted it.

The document featured in DODDOACID derives from a 205-page record of investigation into alleged detainee abuse by a soldier that had been captured on video. The investigation concluded that the actions depicted in the video were inappropriate but not criminal. Holzer found the image on the website of the ACLU, which obtains declassified documents through the Freedom of Information Act. Revealing more about the artful way in which the document was redacted than about the accused or his alleged crime, Holzer's painting calls attention to issues of transparency and privacy.

Why the use of oil paint on linen, a more traditional medium in which she had not worked since her graduate-student days 30 years earlier? "People study and preserve paintings and take them seriously," she explained, "whereas the information wasn't always noticed or taken seriously." Her silk-screened paintings of readymade images recall Andy Warhol's works of the early 1960s, including the Gallery's Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (Rauschenberg Family), 1963. Holzer's crisp enlargements, however, stand in contrast to Warhol's messier technique.

DODDOACID is part of a generous gift of six Redaction Paintings given by the artist to the Gallery in 2010.Jenny Holzer, American, born 1950, DODDOACID, 2007, oil on linen, overall: 147.32 x 111.76 cm (58 x 44 in.), Gift of the Artist © Jenny Holzer, 2010.78.6

Thomas Moran, American, 1837–1926, Green River Cliffs, Wyoming, oil on canvas, 1881, Gift of the Milligan and Thomson Families

Thomas Moran, American, 1837–1926, Green River Cliffs, Wyoming, oil on canvas, 1881, Gift of the Milligan and Thomson Families

In June 1871, Thomas Moran, a gifted young artist working in Philadelphia, boarded a train that would take him to the far reaches of the western frontier and change the course of his career. Just a few months earlier he had been asked to illustrate a magazine article describing a wondrous region in Wyoming called Yellowstone—rumored to contain steam-spewing geysers, boiling hot springs, and bubbling mud pots. Eager to be the first artist to record these astonishing natural wonders, Moran quickly made plans to travel west.

Yellowstone was Moran's ultimate destination in the summer of 1871, but before he reached the land of geysers and hot springs, he stepped off the train in Green River, Wyoming, and discovered a landscape unlike any he had ever seen. Rising above the dusty railroad town were towering cliffs, reduced by nature to their geologic essence. Captivated by the bands of color that centuries of wind and water had revealed, Moran completed a small field study he later inscribed "First Sketch Made in the West." Moran went on to join F. V. Hayden's survey expedition to Yellowstone and complete the watercolors that would later play a key role in the Congressional decision to set the region aside as America's first national park. Over the years, however, the subject Moran returned to repeatedly was the western landscape he saw first—the magnificent cliffs of Green River.

Green River, Wyoming, was a bustling railroad town when Moran arrived in 1871. Three years earlier, Union Pacific construction crews had arrived intent on bridging the river. Their tent camp quickly became a boomtown boasting a schoolhouse, hotel, and brewery. Yet none of these structures appear in Moran's Green River paintings. Even the railroad is missing. Instead, the dazzling colors of the sculpted cliffs and an equally colorful band of Indians are the focus. In a bravura display of artistic license, Moran erased the reality of advancing civilization, conjuring instead an imagined scene of a pre-industrial West that neither he nor anyone else could have seen in 1871. Ten years after his first trip west, Moran completed Green River Cliffs, Wyoming, the most stunning of all his Green River paintings.

The National Gallery of Art is honored to announce the acquisition of Thomas Moran's Green River Cliffs, Wyoming, 1881, a gift of the Milligan and Thomson Families.

Thomas Moran, American, 1837–1926, Green River Cliffs, Wyoming, 1881, oil on canvas, overall: 63.5 x 157.5 cm (25 x 62 in.) framed: 109.22 x 203.2 x 15.24 cm (43 x 80 x 6 in.), Gift of the Milligan and Thomson Families, 2011.2.1

JoaquÍn Torres-GarcÍa, Untitled Composition, 1929, Gift of Victoria and Roger Sant

JoaquÍn Torres-GarcÍa, Untitled Composition, 1929, Gift of Victoria and Roger Sant

The peripatetic Joaquín Torres-García (1874–1949) was already 55 years old with a long career behind him by the time he created this work in 1929. When he was a young painter in Barcelona, his imagination had been fired by art nouveau and the murals of Puvis de Chavannes. In the 1920s he had experimented with cubism and primitivism and had met many leading modernists. But it was not until 1928, two years into a new life in Paris, that he began, through the abstract paintings of Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg and the movement known as De Stijl, to find his own way.

This painting is one of a few in which Torres-García arrived at his mature style. His allegiance to De Stijl is evident in the vertical-horizontal grid and the restriction of his palette to the three primary colors, albeit muted. The delicate layering and subtle painterly touch, however, are all his own—as are the symbols filling the grid. They embody what Torres-García would call "universal constructivism," which proposed a harmony between the intellect (represented here by the triangle and clock), the emotions (the house), and nature (the fish and the elephant). When he returned to Montevideo, Uruguay, his birthplace, in 1934, Torres-García expanded this system to include pre-Columbian elements, but he remained faithful to its basic outlines for the rest of his career.

In Uruguay, Torres-García shook up the academic establishment and became a leading teacher and proponent of modernism, laying the groundwork for the explosion of neoconstructivism in postwar Latin America. He was also influential in New York, where a posthumous exhibition at the Sidney Janis Gallery in 1950 was admired by Barnett Newman and may have influenced Adolph Gottlieb and Louise Nevelson. His fascination with the compartmentalization of signs has its legacy in works by Jasper Johns, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, and others.

Untitled Composition, a gift of Vicki and Roger Sant, was originally bought from the artist by his good friend, the sculptor Jacques Lipchitz, soon after it was made, and it remained with the Lipchitz family. The work has rarely traveled, which explains its pristine condition. This gift brings the Gallery its first painting by the artist and lays the basis for further acquisitions of Latin American modernism, a major ambition in our collecting.

Joaquín Torres-García (artist), Uruguayan, 1874–1949, Untitled Composition, 1929, oil on canvas, overall: 60.01 x 73.03 cm (23 5/8 x 28 3/4 in.), Gift of Victoria and Roger Sant, 2010.15.1

James Rosenquist, American, born 1933, Spectator - Speed of Light, 2001

James Rosenquist, American, born 1933, Spectator - Speed of Light, 2001

James Rosenquist gained recognition in the early 1960s for paintings in which he juxtaposed images culled from the commercial world but radically altered their size and context. As a leading pop artist alongside Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, he aimed to paint contemporary life, not the tired drips, smears, and splatters of his abstract expressionist predecessors. Spectator—Speed of Light, 2001, however, is the work of the mature Rosenquist, who had come to recognize pieces by the likes of Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning as fresh and stimulating.

Rosenquist has always painted by hand, and close viewing of his canvases reveals a surprisingly brushy style. This is especially true of Spectator—Speed of Light. When viewed from a distance,the painting features a shiny, metallic ribbon, twisting and turning through the picture space. Seen at arm's length, however, the reflective surface dissolves into an abstraction of lines and blobs—completely unrecognizable as a real thing. This effect is something Rosenquist experienced as a young man painting billboards: he could never see the whole picture while working on one part. Spectator—Speed of Light plays with this dislocating encounter, blurring the distinction between abstraction and figuration as one moves backward and forward in front of the painting.

For the Speed of Light series, Rosenquist drew on Albert Einstein's theory of relativity, which describes how someone traveling in space at or near the speed of light would have a very different experience of time and distance relative to a slower-moving observer on earth. Spectator—Speed of Light seems to materialize Einstein's theory in a vortex of bright colors and shapes, a rush of the artist's thoughts and gestures. Scale, size, and space are crucial here, as indeed they have always been for Rosenquist, both in the distorted relationships between elements within his compositions and in the sheer size of his canvases: his famous painting F-111, 1964–1965, measures 10 x 86 feet. "I want people who look at my paintings to be able to pass through the illusory surface of the canvas," he wrote in his 2009 memoir Painting Below Zero, "and enter a space where the ideas in my head collide with theirs."

Spectator—Speed of Light was generously donated by Mr. Robert E. Meyerhoff. It is the second painting by the artist to enter the collection, joining White Bread, 1964, which was purchased in 2008.

James Rosenquist, American, born 1933, Spectator—Speed of Light, 2001, oil on linen, overall: 182.9 x 182.9 cm (72 x 72 in.) Collection of Robert and Jane Meyerhoff 2010.14.2

Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse, Fantasy Bust of a Veiled Woman (Marguerite Bellanger?), c. 1865/1870

Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse, Fantasy Bust of a Veiled Woman (Marguerite Bellanger?), c. 1865/1870

Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse (1824–1887) was one of the most talented and prolific French artists of the nineteenth century. After training in decorative metalwork in Paris, he oversaw the Minton china works beginning in 1850. He then became the director of the Sèvres porcelain manufactory, serving in that capacity from 1876 until his death. His unabashedly glamorous, decorative terracottas are archetypal products of the hothouse atmosphere of France's Second Empire; indeed, the idea that this recently acquired sculpture portrays the actress Marguerite Bellanger, who was briefly Napoleon III's mistress, stems directly from the character of the epoch.

The vivaciousness and warmth of Carrier-Belleuse's terracottas supplanted the cold stiffness of earlier neoclassical and academic marble sculptures. Inspired by Clodion, Jean-Antoine Houdon, and other eighteenth-century masters, Carrier-Belleuse exercised his extraordinary facility in modeling to create a multitude of statuettes, decorative busts, and portraits whose beguiling verve contributed to the rococo revival and a renewed taste for terracotta. Responding to broad demand for his art, Carrier-Belleuse produced multiple examples of original models, but by reworking the clay or plaster of a cast sculpture as it came from the mold and was still malleable, he ensured a measure of variety and freshness in his astonishing production, which was unsurpassed by contemporaries.

Fantasy Bust of a Veiled Woman is one of three known examples of the same composition. Previously unrecorded, it is the best version. The others are a painted plaster in the Museum of the Second Empire at the chateau of Compiègne, France, and a partially stripped and repainted terracotta in the Carnavalet Museum, Paris. All were mold-made, but in this sculpture a few mold lines, almost as fine as human hairs, have been preserved. They are evidence of the precision and technical quality of this bust, the style of which may ultimately have been inspired by late sixteenth-century French sculptures such as Germain Pilon's renowned Virgin of Sorrows (marble example in Saint-Paul-Saint-François, Paris; terracotta in the Louvre), with its heavy veil.

At various junctures (1864 and 1870/1871 in Paris and Brussels; 1879 and 1882 at Sèvres) Carrier-Belleuse employed Auguste Rodin (1840–1917) as an assistant. It was in Carrier-Belleuse's well-organized studios that Rodin learned how to manage the large-scale workshops of his maturity. Rodin probably also gained his mastery of mold-made sculptures from Carrier-Belleuse. The similarity between the two artists was a significant consideration in the purchase of this terracotta. The similarity of the National Gallery's Bust of a Woman, 1875, by Rodin, and Fantasy Bust by Carrier-Belleuse is easy to recognize.

Over the past decade, the Gallery has acquired three large, nineteenth-century academic marble sculptures: Nydia, the Blind Girl of Pompeii by Randolph Rogers; Reading Girl by Pietro Magni; and David Triumphant by Thomas Crawford. The Fantasy Bust balances these works and, more significantly, provides a welcome link between them and Rodin. By contributing to a much-needed stylistic and historical context for the Gallery's sculptures by Rodin, the Fantasy Bust of a Veiled Woman also strengthens the chronological coherence of the collection.

Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse, Fantasy Bust of a Veiled Woman (Marguerite Bellanger?), c. 1865/1870, New Century Fund, 2010.63.1

In 2005, the year before his death, Nam June Paik created Ommah ("mother" in Korean), his last work of video sculpture, a genre that he invented in the early 1960s. The work is a moving summary as well as a lighthearted look back at a long and winding career.

In Ommah, a traditional robe that might have been worn by a well-off Korean boy some 100 years ago hangs nearest to the viewer. Through its lightweight silk, images on an LCD TV monitor can be seen, but not without the irritation of a moiré pattern caused by the interplay of the two "screens." The monitor plays a program lasting several minutes and looping continuously. Three Korean American girls in traditional costumes dance, play ball, beat a drum, and ride in a toy car, seemingly carefree but carefully choreographed by Paik. The back-ground imagery includes close-up views of early video games, footage from TV shows, and material from Global Groove, the video Paik made for WNET-TV in 1974, all manipulated using a high-tech version of the color video synthesizer Paik coinvented around 1970. The music includes ambient sounds of the studio, both straight and processed, and snippets from Paik's own experimental music tapes of the 1950s.

As stable and iconic as this cruciform work appears, our physically moving before it is vital as we pass back and forth, trying to peer through or around the robe. Paik attacked the passivity that he felt television imposed on viewers. Through endless play with the medium, he reclaimed the "boob tube" as an expressive, democratic tool. A Fluxus-inspired trickster crossing high culture with low, Paik never lost the homemade, improvised quality of his earliest experiments.

To complement this gift of the Collectors Committee, Paik's nephew Ken Hakuta has donated an early work. Untitled (Red Hand), 1967, also employs a found antique as a screen (in this case a 19th-century Japanese scroll painting) through which light (in this case a blinking bulb) is projected. The bulb illuminates a handprint, presumably the artist's own, made on the glass of the frame. The scroll's comical figure with bulging eyes combines with these other elements in a humorous meditation on authorship and scavenger hunting, technology and tradition. Together these two works constitute a landmark acquisition: they are the first sculptural objects by Paik to enter the collection, and Ommah is a key addition to our nascent collection of works in time-based media.

Nam June Paik (artist), American, born South Korea, 1932 - 2006, Ommah, 2005, one-channel video installation on 19-inch LCD monitor, silk robe, Gift of the Collectors Committee, 2010.62.1

John McCracken, Black Plank, 1967, Gift of the Collectors Committee

John McCracken, Black Plank, 1967, Gift of the Collectors Committee

In the landscape of minimalism, John McCracken cuts a unique figure. He is often grouped with the "light and space" artists who formed the West Coast branch of the movement. Indeed, he shares interests in vivid color, new materials, and polished surfaces with fellow Californians enamored of the Kustom Kar culture. On the other hand, his signature works, the "planks" that he invented in 1966 and still makes today, have the tough simplicity and aggressive presence of New York minimalism.

"They kind of screw up a space because they lean," McCracken has said of the planks. Their tilting, reflective surfaces activate the room, leaving the viewer uncertain of traditional boundaries. He notes that the planks bridge sculpture (identified with the floor) and painting (identified with the wall). If Donald Judd's "specific objects" aspired to be "neither painting nor sculpture," as he wrote, McCracken's planks aspire to be both.

"I want to make sculpture out of, say, 'red' or 'blue,'" McCracken once noted in a sketchbook. To do so required great craft. The original planks were hollow plywood structures sprayed with paint, but the wood grain began to show through once the paint dried. He solved the problem by coating the plywood with a layer of fiberglass before painting and using power sanders afterward to remove any personal or organic texture from the final surface.

Black Plank, an early and rare work in pristine condition, reflects the artist's love of "an ancient Egyptian portrait of Chephren, in black diorite." For McCracken, who admits to believing in UFOs and aliens, each plank has its own personality, indeed its own being. From these idiosyncratic ideas, or perhaps in spite of them, his arresting work emerges. His ultimate goal, as with all mystics, is unity—not just of painting and sculpture, but of substance and illusion, of matter and spirit, of art and life. Such ideas recall the utopian aspirations of early modernists like Piet Mondrian and Wassily Kandinsky.

Thus McCracken's work not only engages with the Gallery's strong holdings of minimalism—including pieces by Judd, Carl Andre, Robert Morris, Fred Sandback, Anne Truitt, James Turrell, and Larry Bell—but also with our paintings by Barnett Newman, whose "zips" helped inspire the planks, and with our major works of early abstraction. Black Plank is a gift of the Collectors Committee and is the first work by this fascinating artist to enter the Gallery's collection.

John McCracken, American, born 1934, Black Plank, 1967, polyester resin, fiberglass, and plywood, overall: 243.84 x 40.64 x 6.35 cm (96 x 16 x 2 1/2 in.), Gift of the Collectors Committee, 2010.18.1

![]() David Reed, #421(1), #421(2), #421(3), #421(4), 1998, oil and alkyd on polyvinyl polymer resins, Dorothy and Herbert Vogel Collection

David Reed, #421(1), #421(2), #421(3), #421(4), 1998, oil and alkyd on polyvinyl polymer resins, Dorothy and Herbert Vogel Collection

David Reed has said that he sees his paintings titled consecutively #421(1), #421(2), #421(3), and #421(4) as completed color studies. This observation reinforces the significance of the transparent and opaque layers of color that he combines with fluid, plastic lines laid down on the smooth surfaces of polyvinyl polymer resin panels. Reed used tape to mark out areas before applying alkyd impastos to the panels, leaving some areas flat and others in thin relief. Alkyd, a material that artists began to accept in the 1970s, dries quickly compared with oil paint and yet retains, like oil paint, its brilliant, even color and the appearance of wetness even after it solidifies. Painting forms that seem to hang or float in space, Reed bends serpentine lines like ribbons, curled and redoubled, sometimes tightly framed and sometimes loosely contained within rectangular boundaries.

Reed's drawings suggest that he plans out the overall composition of a painting, since they contain notes, diagrams, and swatches of color on quadrille paper, but this is not the case. "I do not want people to think that the paintings are preplanned," he said in an interview: "My decisions are made in the process of painting. My plan is always changing."

Reed has said that his work is neither nostalgic nor separate from life, that the past is a place to revisit only insomuch as it has relevance to the present. His colors may bring to mind those of the Day-Glo 1960s pop or op screenprint, and indeed layering of vibrant flat color is a key formal component of his work. Yet colors like hot pink, turquoise, and purple could also be associated with the cartoons and popular culture of today. Similarly, his drips and strokes might recall Jackson Pollock or abstract expressionist gesturalism, except that they look as if they have displaced a kind of film on the surface of the panel, like writing in fog on a window. Atomized lines of color drawn with an airbrush suggest that the same tool might have been used to create that film. Reed also uses glazes which create effects which are more like what one might expect from ink on vellum rather than oil on canvas.

Reed's forms appear to twist in space and yet at the same time are composed of one plane laid over another. As the artist adds layer upon layer, without any of the paint soaking in, since he lets each layer dry, what happens on each plane remains fundamentally isolated from what happens on the next.

These four acquisitions compliment the one painting by Reed already in the Gallery's collection. A generous gift from Dorothy and Herbert Vogel, these paintings are now part of the Herbert and Dorothy Vogel Collection.

David Reed, #421(1), #421(2), #421(3), #421(4), 1998, Dorothy and Herbert Vogel Collection, 2007.6.240

Adam van Breen, Skating on the Frozen Amstel River, 1611, The Lee and Juliet Folger Fund, in honor of Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr.

Adam van Breen, Skating on the Frozen Amstel River, 1611, The Lee and Juliet Folger Fund, in honor of Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr.

Winter is the most frequently represented season in Dutch seventeenth-century art. One of the finest artists to paint winter scenes was Hendrick Avercamp (1585–1634), whose depictions of young and old, rich and poor populating frozen waterways were recently featured in an exhibition at the National Gallery of Art. However, Avercamp was neither the first nor the only Dutch artist to paint this type of winter scene. While the exhibition of his paintings and drawings filled the walls of the Dutch Cabinet Galleries, the Gallery's permanent collection was enriched with a delightful winter scene by one of his contemporaries, Adam van Breen's Skating on the Frozen Amstel River (1611).

Much like Avercamp, Van Breen depicted Dutch citizens enjoying a bright wintery day, capturing the excitement when the ice was finally strong enough to welcome skaters. In the foreground are elegant figures dressed in vibrantly colored clothes preparing to skate, while others happily glide into the distance, along the smooth surface of the frozen river. Characteristic of these paintings are the many anecdotes that are illustrated, for example a young boy who propels himself on his prikslee (a small push-sled); an ice boat under full sail; and an orphan from the Burgerweeshuis (City Orphanage) of Amsterdam, recognizable by his half-red, half-black costume, carrying a kolf-stick over his shoulder. Occasionally accidents occur, as in the middle distance where two figures are sprawled on the ice.

This particular painting is unusual in the geographical accuracy of the buildings. Instead of an imaginary city, the artist staged the figures against the profile of Amsterdam. The view is along the river Amstel, just south of that city. The church spires punctuating the city's profile are those of the Nieuwe Kerk, the Oude Kerk, and the nearest, the Zuiderkerk. The Zuiderkerk was built between 1603 and 1611, and this painting is the first depiction of this newly constructed Protestant church.

Little is known about Van Breen's origins or his artistic training. His small surviving oeuvre consists mostly of winter landscapes, similar to those painted by Avercamp. Both artists may have studied in Amsterdam with David Vinckboons (1576–1633). Van Breen later moved to The Hague, where he married before he returned to Amsterdam. Eventually, he immigrated to Norway where he worked for King Christian IV. This beautifully executed and topographically interesting painting is one of his earliest known works and the earliest Dutch seventeenth-century painting in the Gallery's collection.

Adam van Breen (artist), Dutch, c. 1585 - 1640, Skating on the Frozen Amstel River, 1611, oil on panel, overall: 43 x 65 cm (16 15/16 x 25 9/16 in.) framed: 78.74 x 55.88 x 5.08 cm (31 x 22 x 2 in.), The Lee and Juliet Folger Fund, in honor of Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr., 2010.20.1

Sean Scully, ONEONEZERONINE RED, 2009, Gift of Alan and Ellen Meckler

Sean Scully, ONEONEZERONINE RED, 2009, Gift of Alan and Ellen Meckler

Since the mid-1970s, Sean Scully has painted stripes and variations thereof (blocks, bands, and so forth). He is, of course, not the only artist to do so: other notable examples include Frank Stella, Agnes Martin, and Gene Davis. Yet Scully's canvases are unmistakably his own, thanks to their distinctive architecture of horizontal and vertical elements, their soft but muscular paint handling, and their earthy colors.

Scully uses this basic, abstract vocabulary—which he says relates to the "repetitive building techniques that populate the whole world"—to communicate with the broadest possible audience. As a modernist, Scully believes in artistic evolution and the constant struggle to improve; he also believes in the power of abstraction as a universal language, to say everything all at once. Figurative painters are limited by their particular content; an abstract painting, according to Scully, "should be, could be, possibly, a moment of revelation. It's a kind of thinking that takes you out of context."

Scully begins each painting with a charcoal underdrawing in which he lays out the basic composition. He then paints wet on wet until he feels he has "got it." Sometimes he completes a picture in one round, and other times he must repeat this process over several days. The many layers of paint in ONEONEZERONINE RED, a 2009 work generously donated by Alan and Ellen Meckler, seem to break down the strict geometry of the four-part composition. There is a tension between the architecture of the composition and the looseness of the brushstroke. No visual hierarchy governs the picture space. Every block has its place, balancing or propping another block. Some colors come forward and others recede.

ONEONEZERONINE RED has a luscious, glossy surface. This gives it a lightness that stands in stark contrast to Scully's very physical multipanel paintings of the 1980s, of which the National Gallery's All There Is, 1986 (Gift of William Zachs), is a prime example. Composed of four attached panels, the earlier painting has a raw surface texture reminiscent of burlap, an effect the artist likely achieved by dragging a large, stiff-bristled brush through tacky paint. ONEONEZERONINE RED is much more refined. The brushstrokes are more fluid, the touch more elegant.

The title of ONEONEZERONINE RED comes from the date, 1.1.09, inscribed on the back of the painting above the artist's signature. It hints at the immediacy of Scully's process and marks a singular moment in this artist's gradual, deliberate evolution.

Sean Scully (artist), American, born Ireland, 1945, ONEONEZERONINE RED, 2009, oil on linen, overall: 228.6 x 182.88 cm (90 x 72 in.), Gift of Alan and Ellen Meckler, 2009.125.1

Thomas Chimes, Messenger, 1989, Gift of Gene and Sueyun Locks

Thomas Chimes, Messenger, 1989, Gift of Gene and Sueyun Locks

At first glance, Thomas Chimes' 1989 painting Messenger might appear to be an abstract monochromatic canvas. Slowly, though, a hazy profile emerges from the white field. Tiny words dot the canvas and skim the bottom edge. This mysterious painting begs to be deciphered.

Chimes' work has been described as hermetic. He was fascinated with mythology, alchemy, and the French poet and playwright Alfred Jarry (1873–1907). The head in Messenger comes from an 1897 photograph of Jarry on his new Clément Luxe 96 bicycle, which he was famous for riding. In the early 1980s, Chimes began inserting this image into landscape paintings. He replaced the bicycle, however, with two oars and transformed the writer into one of his characters, Dr. Faustroll, who traversed Paris in a skiff. In 1984, Chimes began a series of Faustroll paintings (Messenger, for one) in which the artist cropped away the body and drained his palette of color, using only titanium white and Mars black.

The layers of white paint that veil the photo-based image also seem to blast it with light. That whiteness may suggest "emerging consciousness," as Chimes said, or perhaps inner illumination. Two quotations (one in French, one in Greek) are carved into the paint at the bottom edge of the canvas. The first, translated from Jarry's Exploits and Opinions of Doctor Faustroll, Pataphysician, reads, "God is the tangential point of zero and the infinite. Pataphysics is the science." The second, in translation, is a query, "Why speak of manifold matter, [when] one substance is nature, and one nature conquers all?" This line is attributed to the Greek alchemical writer Zosimus, active in the third century AD, possibly quoting the pre-Socratic philosopher Democritus. Scattered around the canvas are the Greek words for messenger, air, fire, night, and water, and the names Maia and Hermes. What does it all mean? The painting raises questions about truth and nonsense, appearance and disappearance, clarity and obscurity.

Born in 1921 in Philadelphia to Greek immigrant parents, Chimes studied briefly at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, then left to serve in World War II. In 1946 he settled in New York, where he studied philosophy at Columbia University and painting and sculpture at the Art Students League. He also met the artists Barnett Newman, Theodoros Stamos, and William Baziotes. Chimes moved back to Philadelphia in 1953. A great admirer of Thomas Eakins and Edgar Allan Poe, two Philadelphians who came before him, Chimes enjoyed a long career out of the limelight and developed his own vocabulary. In his sixties, Chimes took to wearing a porkpie hat and began to strongly resemble Jarry. Messenger, then, can also be read as a self-portrait.

Thomas Chimes (artist), American, 1921 - 2009, Messenger, 1989, oil on wood, overall: 76.2 x 83.5 cm (30 x 32 7/8 in.), Gift of Gene and Sueyun Locks, 2009.122.1

George Segal, Wendy with Chin on Hand, 1982, Gift of The George and Helen Segal Foundation

George Segal, Wendy with Chin on Hand, 1982, Gift of The George and Helen Segal Foundation

American sculptor George Segal (1924–2000) is known for his ghostly white figures created by casting directly from the human body using gauze strips impregnated with plaster. Wendy with Chin on Hand, 1982, is a partial bronze bust of Wendy Worth, his longtime model, for which Segal cast only her face, hand, and shoulder. Clearly related to his Fragments series, the white-painted sculpture echoes classical marbles that were often unearthed in pieces and lacked their original polychromy. Its surface is far less refined than any Roman or Greek antecedent, however, retaining as it does all the evidence of the messy casting process.

In addition, the pose, which at first glance suggests a classical elegance and balance, is in fact a result of contortion or perhaps even piece-by-piece assemblage, for it is the model's right hand, not the left, that touches the right shoulder—a position no one would adopt naturally or even easily. In this way both pose and surface manifest the artificial, constructed nature of this beautiful illusion. Despite the literal nature of the body-casting process, this muse is very much the artist's creation.

Segal's casting process evolved over the course of his career. In the 1960s he used a single-cast method, wrapping his model in plaster-soaked strips, letting them dry, and then cutting the strips off in pieces and reassembling them to create the finished work. Thus all the detail captured at the interface of plaster and body ended up on the inside of the hollow sculpture, while the outside retained the evidence of Segal's handling of the plaster. As a result, his figures appeared mummified and anonymous. In the early 1970s he began taking secondary casts, using the hollow primary casts as molds. This more traditional approach brought the once-hidden details from the interior to the surface of the sculpture. And in 1976, prompted by a commission for an outdoor sculpture, Segal began casting select plasters in bronze. After 1979, when a white patina for bronze was invented, he was finally able to give his bronze sculptures the look of plasters.

Thanks to a generous gift of the Helen and George Segal Foundation, Wendy with Chin on Hand is the fifth sculpture by the artist to enter the National Gallery's collection. Among the holdings is, most notably, The Dancers, another 1982 bronze (a Collectors Committee purchase) that depicts four women awkwardly arranged in a circle, each intensely focused on her own deliberate pose. The Dancers is an impressive and large composition and is among the finest examples of Segal's newfound ability to duplicate the original plaster, which in this case was cast ten years earlier, in bronze. Wendy with Chin on Hand, by contrast, is the smallest Segal sculpture to enter the collection to date and offers a more intimate glimpse into the artist's practice.

Wendy with Chin on Hand, George Segal (artist), American, 1924–2000, , 1982, bronze with white patina, overall: 36.2 x 25.72 x 21.59 cm (14 1/4 x 10 1/8 x 8 1/2 in.), Gift of The George and Helen Segal Foundation, 2009.105.1

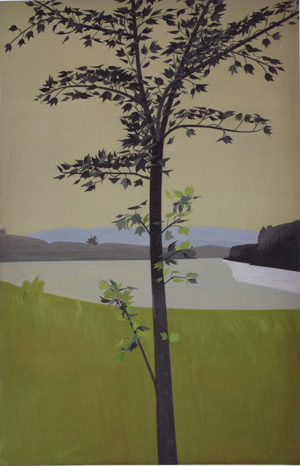

Alex Katz, Folding Chair, 1959, Gift of The Alex Katz Foundation

Alex Katz, Folding Chair, 1959, Gift of The Alex Katz Foundation

Alex Katz was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1927 and educated at Cooper Union. Although he fraternized in the 1950s with the abstract expressionists at the Cedar Bar, their hangout in Greenwich Village, Katz never embraced the gestural style popular in New York, clinging instead to some degree of observation. (In high school he had received traditional training that included drawing from antique casts.) And yet if Katz's work has always celebrated the realism of quotidian life and landscape, it also cunningly incorporates the scale and structure of the ambitious abstract painting of his time.

Folding Chair, 1959, with its restrained elegance, is a stately example of this abstracted realism. Katz simplifies the image to its essentials. A pale folding chair meets the olive plane of the floor and gridded windows of that city in a tilted space that opens wide to the viewer and defies perspective. The mode was not well received at first. to Katz's 1959 solo show at the TanagerVisitors Gallery unfavorably compared his paintings to photographs. Although Katz did paint from snapshots in the early 1950s, by the end of the decade he had shifted to painting from life with all the spontaneity of Jackson Pollock, whom he knew and admired. What he retained from his early use of the snapshot as reference were the parameters of the camera aperture, which constrained the scene in question and the viewer's position. At the same time, his rather arbitrary color choices declared his independence from photographic realism.

Abstract expressionist artist Willem de Kooning recognized Katz's painterliness in 1959 and, responding to remarks from his critics, told Katz, "They look like photos, but they are paintings, and don't let them knock you away from it." While the view of Folding Chair appears photographic from across the gallery, a closer look reveals that the spare shapes of the work—one rectangle stacked against another— bear loose brush marks and imprecise edges where one color bleeds into the next.

The composition reflects Katz's use of collage throughout the 1950s to consider the relationships between flat planes of color. Inspired by Henri Matisse's deliberate use of collage in his Cut-Outs, Katz avoided the sometimes haphazard nature of a medium based on scrap material. He purchased beige sheets of paper, hand-painted them in flat washes, and cut them into precise shapes that he then arranged on a page. One can easily imagine the correspondence between collage and canvas in Folding Chair: painted images of a white windowpane or green wall may well have replaced tiles of paper.

Folding Chair is a significant addition to the National Gallery's strong collection of postwar American painting and offers an opportunity to examine Katz's early blurring of the boundary between abstraction and realism. In its juxtaposed planes of color and flattened spaces, the work presages the stark compositions of Katz's later pictures, of which the Gallery's other Katz painting, Swamp Maple (4:30), 1968, is a major example. Folding Chair was a generous gift from the Alex Katz Foundation.

Alex Katz, American, born 1927, Folding Chair, 1959, oil on canvas, overall: 121.3 x 123.8 cm (47 3/4 x 48 3/4 in.), Gift of The Alex Katz Foundation, 2009.104.1

Robert Morris, Untitled, 1976, felt

Robert Morris, Untitled, 1976, felt

Robert Morris is perhaps the single most important figure for understanding the shift from minimal to postminimal art. As a pioneer of minimal sculpture during the early 1960s, Morris was one of the first artists to take into account the spatial and physical relationship between a viewer's body and a work of art. In columns, cubes, boxes, and L-beams, Morris's early works explored the body's interaction with specific objects and forms. As he explained in an interview with the critic E. C. Goossen, "I'm very much involved with that relationship towards things that has to do with the body's response."

By the late 1960s, Morris was already experimenting with what he termed "anti form." Turning away from the modular construction of his earlier sculptures, Morris began making works in materials such as felt, thread waste, and even steam in order to explore the unusual properties of these different media. In 1967 he began a series of works using industrial felt—seeing how it behaved when stacked, draped, folded, hung, cut into pieces, or dropped into a tangled heap. The following year Morris articulated the stakes of his new concerns in an Artforum essay titled "Anti Form," in which he stated: "Random piling, loose stacking, hanging, give passing form to the material. Chance is accepted and indeterminacy is implied since replacing will result in another configuration." What Morris was at pains to emphasize, in other words, is that a single "anti form" work holds the potential to take a different shape each time it is presented, based on the arbitrary behavior of the materials from which it is composed.

Untitled, 1976, is from the seminal Felts series. Although hung on a wall like a painting, this stubbornly tactile work compels both through its unpredictable form and its assertive physical presence, putting it in dialogue with National Gallery works by Eva Hesse and Richard Serra among others.

Robert Morris, American, born 1931, Untitled, 1976, felt overall: 183 x 365.8 x 1.6 cm (72 1/16 x 144 x 5/8 in.) Gift of the Collectors Committee 2007.36.1

Fred Sandback, Untitled (Gray Corner Construction), 1968, gray acrylic on steel and elastic cord

Fred Sandback, Untitled (Gray Corner Construction), 1968, gray acrylic on steel and elastic cord

In his 1941 book Space, Time, and Architecture, Sigfried Giedion argued that modernism was distinctive for its use of the void as a positive element. No artist exemplifies this better than Fred Sandback, who spent 35 years making sculptures virtually without mass or volume, but as lines in space.

This work began in 1967, while Sandback was earning his M.F.A. in sculpture at Yale. The example of visiting artists Donald Judd and Robert Morris helped him reject the ideal constructivist forms of Naum Gabo (whom Sandback had also met) and articulate real space by stretching elastic cords across parts of rooms. Perhaps he was responding to Michael Fried's 1967 essay "Art and Objecthood," which criticized minimalist objects for seeming hollow despite their bulk; perhaps he was inspired by the openness of Morris' steel-mesh sculptures, which Fried had ignored. In any case, Sandback began using hollowness itself to create almost palpable shapes. Soon he moved from elastic cord to acrylic yarn, which allowed him to explore color and span greater distances, achieving a desired unboundedness through the use of boundaries alone.