Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT)

Key Points

- SELECT stands for the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial, a prevention clinical trial to see if one or both of these dietary supplements could help prevent prostate cancer. (Question 1)

- In September 2008, SELECT researchers found that selenium and vitamin E, taken alone or together for an average of five and a half years, did not prevent prostate cancer. Men in the study were told to stop taking their study supplements because of this lack of benefit. (Question 2)

- In 2011, updated trial data showed that the men taking vitamin E had a 17 percent increased risk of prostate cancer compared to men taking the placebo.(Question 5)

The Study

What is SELECT?

SELECT stands for the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial. It's a clinical trial to see if one or both of these substances could help prevent prostate cancer when taken as dietary supplements. The trial is funded primarily by NCI and developed and carried out by SWOG, an international network of research institutions. Enrollment for the trial began in 2001 and ended in 2004. More than 400 sites in the United States, Puerto Rico, and Canada took part in the study. Over 35,000 men, age 50 and older at the start of the trial, participated in SELECT (1).What were the initial results of SELECT, as published in 2008?

SELECT was initially planned for a minimum of seven years and a maximum of 12 years of participants taking supplements, plus follow-up observation after the men finished taking their supplements. However, the independent Data and Safety Monitoring Committee (DSMC) for the trial met on September 15, 2008, to review SELECT study data and found that selenium and vitamin E, taken alone or together did not prevent prostate cancer. The committee also determined that it was unlikely selenium and vitamin E supplementation would ever produce a 25 percent reduction in prostate cancer incidence, as the study was designed to show. Based on their recommendation, with SWOG and NCI agreement, SELECT participants were told in October 2008 to stop taking their study supplements.Although there were no statistically significant differences in the rates of prostate cancer between the four groups in the trial, there were more cases of prostate cancer in men taking only vitamin E. Statistical significance describes a mathematical measure of how sure one can be that a difference seen is not due to chance. The difference is said to be statistically significant if it is greater than what might be expected to happen by chance alone. As initially reported in 2008, the observed increase in the number of prostate cancer cases could have been due to chance.

In the 2008 report, there were also more new cases of diabetes in men taking only selenium compared with men taking placebo. This finding was also not statistically significant and did not prove an increased risk from selenium. Initial results of SELECT were published online in JAMA-Express on December 9, 2008 and appeared in the first print edition of JAMA in January 2009. (2)

In the 2008 report, did the supplements reduce the risk of any disease?

No. There was no difference in the incidence of lung or colorectal cancers, all cancers combined, all deaths combined, or the overall incidence of cardiovascular events between the study groups.What is new about the updated (2011) SELECT results?

The data published in 2011 include 18 months of additional follow-up information on the participants through July 5, 2011. During this time, SELECT men were no longer taking study supplements. These additional data provide an average of seven years of information on the participants: 5.5 years taking study supplements plus 1.5 years of observation or follow-up.What are the updated (2011) results of SELECT?

The additional data show that the men who took vitamin E alone had a 17 percent relative increase in numbers of prostate cancers compared to men on placebo. This difference in prostate cancer incidence between the vitamin E only group and the placebos only group is now statistically significant, and not likely to be due to chance.Men taking selenium alone, or vitamin E and selenium, were also more likely to develop prostate cancer than men taking placebo, but those increases were smaller and are not statistically significant and may be due to chance. Updated results of SELECT were published in JAMA on October 12, 2011 (3).

Do we know why an increased risk for prostate cancer was found in 2011 vs. 2008?

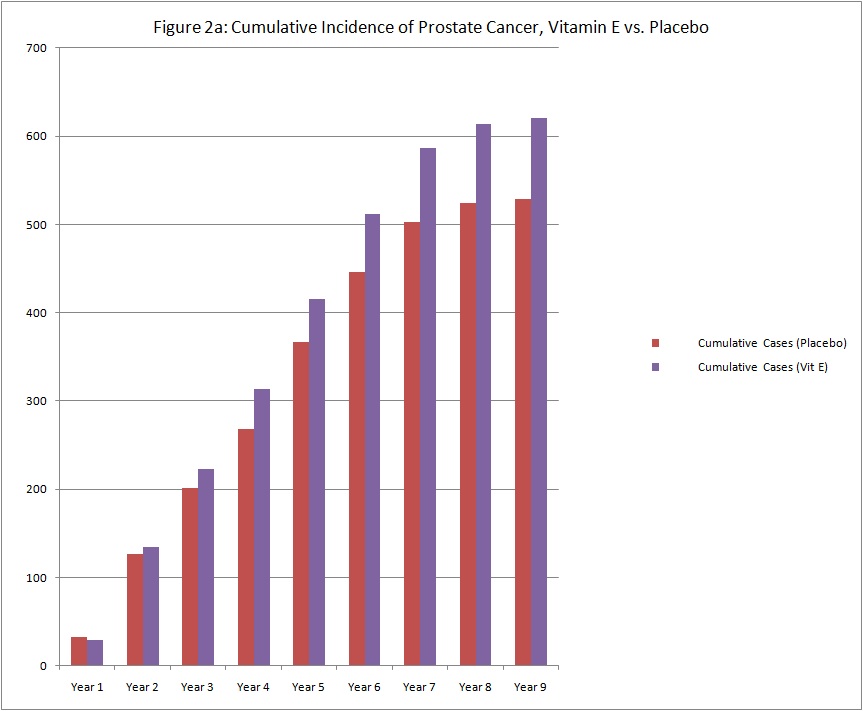

As with many medications, the actions of vitamin E may last long after the last pill is taken. The differences in prostate cancer incidence between the vitamin E group and the placebo group began to emerge at about the third year of study supplementation (see graph below of cumulative cases).

The observation that the risk of prostate cancer has continued to increase suggests that vitamin E may have long-term effects on prostate cancer risk. SELECT researchers will continue to follow the study participants to see whether the increased risk continues with longer time off of the supplements.With this additional information, was there any difference in other cancers or diseases from SELECT supplements?

There continue to be no differences in the incidence of lung or colorectal cancers, all cancers combined, all deaths combined, or the overall incidence of cardiovascular events between the study groups. Although initial results showed that more men taking selenium were diagnosed with diabetes, longer follow-up showed no increased risk of this disease.What does a 17 percent increased risk of prostate cancer mean?

In SELECT, this measure means that there were 17 percent more prostate cancer cases diagnosed in the group of men assigned to take 400 International Units (IU) of vitamin E (and no selenium) daily compared to the men taking two placebos (no vitamin E and no selenium), after an average of seven years -- 5.5 of the years on supplements followed by 1.5 years not taking supplements.In the men in SELECT who took only placebos, after seven years, 65 prostate cancer cases were diagnosed for every 1,000 men. For the men assigned to take vitamin E only, for every 1,000 men, there were 76 cases of prostate cancer diagnosed (11 additional cases of prostate cancer per 1,000 men over seven years).

What does a 17 percent increased risk of prostate cancer mean to men who are taking vitamin E but who are not SELECT participants?

The incidence rate of prostate cancer in the placebo arm of SELECT is similar to the incidence rate for men in the U.S. age 65 and older. (4) Thus, the estimate of increased risk for men of SELECT age taking vitamin E supplements of 400 IUs daily would be about the same as for the men on SELECT taking vitamin E only (i.e. about 17 percent).In other words, if 1,000 men similar to those on SELECT were followed with annual physician visits, one would expect 65 of them to be diagnosed with prostate cancer over a seven year period. If these same men took 400 IUs of vitamin E daily for 5.5 years, researchers would expect 76 of them to be diagnosed with prostate cancer over a seven year period (i.e., 11 additional cases over seven years).

Were the prostate cancers in the men taking vitamin E any different from other prostate cancers?

They were not different based on current clinical measures. In SELECT, although participants had regular visits with study staff, there were no required prostate cancer screening tests. So the researchers checked to see if men in any study arm had screening tests more often than men in the other study groups and if the cancers in any group were more advanced or aggressive than in other groups. Diagnosed tumors were also checked by a central pathology review. None of the groups in SELECT were found to be screened more often than any other, the vast majority of all of the cancers that were screened were very early stage disease, and the rate of advanced or aggressive cancers in the vitamin E group was no higher than in the placebo group. In addition, review of prostate tissues from biopsies by a pathologist did not uncover any other differences in the cancers that developed among the groups of men in SELECT.Why didn't the vitamin E supplements prevent prostate cancer as expected? Why did the men taking vitamin E have more prostate cancers?

There are many reasons why the vitamin E supplements may not have prevented prostate cancer. Two of the most likely reasons look back at the Alpha-Tocopherol Beta Carotene (ATBC) Cancer Prevention trial, a study designed to test vitamin E and beta carotene for lung cancer prevention in smokers (10). In the ATBC, a reduction in prostate cancer incidence was observed, but this secondary finding may have been due to chance, as the study was not designed to determine prostate cancer risk. Another possible reason that men in ATBC had a reduction in prostate cancer incidence, while men on SELECT did not, is that the dose of vitamin E used in SELECT (400 IU/day) was higher than the dose used in the ATBC (50 IU/day). Researchers sometimes talk about a "U-shaped response curve" where very low or very high blood levels of a nutrient are harmful but more moderate levels are beneficial; while the ATBC dose may have been preventive, the SELECT dose may have been too large to have a prevention benefit.Researchers don't know for certain that this is why men in the vitamin E only group had more prostate cancers than other men in SELECT. SELECT researchers are soliciting feedback from investigators nationwide who have ideas about why this may have happened. These researchers were asked to submit a proposal to use the SELECT biospecimen repository to help answer this question. One study already under way is measuring the amount of vitamin E, selenium, and other nutrients in the blood of participants when they joined the trial to see if the effect of the supplements depended upon this baseline level of micronutrient. Other molecular studies are under way or being planned to see if there might be a genetic basis for the increase in risk associated with vitamin E.

Why didn't the men in SELECT taking vitamin E and selenium also have an increased risk of prostate cancer?

Researchers aren't certain why the men in SELECT who took both vitamin E and selenium supplements have not shown a significantly increased risk of prostate cancer. The continuing research on SELECT may help to understand this observation.Should men not take vitamin E supplements? Should they only take them if they are also taking selenium?

There are no clinical trials that show a benefit from taking vitamin E to reduce the risk of prostate cancer or any other cancer or heart disease (2, 3, 5-9). While the men in SELECT who took both vitamin E and selenium did not have a statistically significant increase in their risk for prostate cancer, they also did not have a reduced risk of prostate cancer or any other cancer or heart disease.In 2003, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) concluded that the evidence was insufficient to recommend for or against the use of supplements of vitamins A, C, or E; multivitamins with folic acid; or antioxidant combinations for the prevention of cancer or cardiovascular disease. USPSTF is currently conducting a review of the evidence to update their statement that will include data from SELECT and other studies (http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsvita.htm). The men in SELECT were told to stop taking their study supplements in 2008. Men not in the study who are taking vitamin E supplements may want to discuss the findings from SELECT with their doctor.

What about multivitamins?

SELECT did not study the effect of multivitamins on prostate cancer risk. Additionally, the dose of vitamin E in SELECT was 400 IU per day. Most multivitamins for adult men use a much lower dose of vitamin E, from about 22.5 IU to 60 IU per day.Why did SELECT use a dose of 400 IU of vitamin E? What form of vitamin E was used?

At the time SELECT was being designed, trials to test vitamin E in other common diseases were also under way. These trials were studying 400 IU to 660 IU of vitamin E to prevent macular degeneration, Alzheimer's disease, or heart disease. Preliminary evidence suggested the outcomes would be favorable. SELECT researchers matched the doses in these trials to ensure data at the 400 IU dose was available if using the supplement for other diseases became common.The form of vitamin E given was dl-alpha tocopheryl acetate, the form of vitamin E found to reduce prostate cancer incidence in the ATBC.

Should men who take vitamin E have more prostate cancer screening?

Probably not. There is no evidence that additional or increased screening for prostate cancer will be helpful to men who are taking vitamin E supplements. SELECT did not study specific ways to screen for prostate cancer and did not require participants to have any prostate cancer screening tests. Almost all of the prostate cancers diagnosed among men in SELECT, including those in participants taking vitamin E, were early stage cancers. These cancers were found in the same ways that community doctors routinely take care of their patients. No group of men in the study had more screening tests than any other.Prostate cancer screening is not recommended for all men because it is not known whether the commonly used screening tests (PSA blood test or digital rectal exam) decrease the risk of dying from prostate cancer or whether any benefits outweigh the harms. In 2008, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force concluded that evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of prostate cancer screening in men younger than 75 years of age. They recommended against screening for prostate cancer in men 75 years or older. (see http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsprca.htm). USPSTF review of benefit and harms for younger men is ongoing. Most authorities recommend that men over 50 speak with their doctor about prostate cancer screening and make an individual decision.

Did the African American men in SELECT have any different outcomes compared to the rest of the participants?

Probably not, but the number of African American men in the trial is too small to be certain that separate analyses would be statistically sound. In SELECT, African American men were permitted to join the trial at a younger age than men of other races (at age 50 vs. 55) because of their increased risk of prostate cancer. About 12 percent of the participants (4,314 of 34,888) identified themselves as African-American, and they were represented equally across the study arms (as would be expected in a randomized trial). Although this percentage reflects the proportional representation of African Americans in the United States, the number of men is not large enough to do thorough, separate statistical analyses of each SELECT study endpoint. However, SELECT researchers did look at cancer rates and other measures by race and did not see any differences in the response to the supplements.

Update on the Study Participants

Have the men in SELECT been told what supplements they were taking?

Yes, beginning in late 2008 when the trial was halted, all participants were told which supplements they had been taking.Are the men still being followed at their study centers?

As of 2010, men who agreed to continue on SELECT are followed by a single office in SWOG, the SELECT Coordinating Center. They are enrolled into what is known as Centralized Follow-Up. These participants receive an annual questionnaire to complete by mail or on-line at http://www.crab.org/select, and they receive two newsletters a year. There are over 17,700 participants continuing with SELECT through Centralized Follow Up. Former SELECT participants who did not enroll are still welcome to rejoin by contacting the SELECT Coordinating Center (see question 21). The DSMC will continue to review the study data. The Centralized Follow Up will continue for up to five years, but is dependent on available funding.Were all the participants told about the new findings?

Men who signed up for Centralized Follow Up received letters outlining the latest study findings. If a participant has not agreed to take part in centralized follow-up, SWOG is not legally able to keep their personal contact information, so letters could not be sent from the SELECT Coordinating Center. All investigators who participated in the trial also received information and letters that they can send to former participants.What if a participant has moved or otherwise lost contact with their SELECT study team? How can they join the centralized follow-up of participants or who do they call if they have a general question?

Study sites are now closed and the study is being conducted by the SELECT Coordinating Center in Seattle. Participants should contact the SELECT Coordinating Center, which has maintained the data on all study participants since the trial began. The Coordinating Center can be reached by calling toll free at 1-877-798-5444, Español at 1-877-740-3331 or email at SELECTinfo@lyris.crab.org.

Background About the Trial

Who got which supplement?

SELECT is a randomized, controlled clinical trial. The men who participated took two capsules a day. They were randomly assigned (that is, assigned by chance) to receive:- Selenium and vitamin E

- Selenium and a placebo

- Vitamin E and a placebo, or

- Two placebos. Two placebos were used in the trial: one looked like a selenium capsule; the other looked like a vitamin E capsule. Each placebo contained only inactive ingredients. Neither the participants nor the researchers knew who received the selenium and vitamin E, or the placebos, a process known as blinding or masking. 23.

Who was eligible to participate in SELECT? Were there restrictions on eligibility?

African-American men had to be age 50 or older to participate, and men of other races and ethnicities had to be 55 or older. The age for eligibility was lower for African-American men because, on average, they develop prostate cancer at an earlier age and have an overall increased risk of developing prostate cancer.Many diseases, including prostate cancer, occur more frequently in older persons. The risk of developing prostate cancer increases with age. More than 90 percent of prostate cancer cases occur in men age 55 or older (4).

What are a man's chances of developing prostate cancer?

Except for skin cancer, prostate cancer is the most common type of cancer in men in the United States. In 2011, it is estimated there will be 240,890 new cases of prostate cancer and 33,720 deaths from this disease (4). All men are at risk for prostate cancer, but those at highest risk fall into one or more of the following categories: age 55 years or older; African American; have a father or brother with prostate cancer. About one in six men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer in their lifetime.Why was a randomized, controlled clinical trial necessary?

Evidence from epidemiologic studies, observational studies, and clinical trials looking at preventing cancers other than prostate cancer had suggested that selenium and/or vitamin E might prevent prostate cancer. In order to know with certainty that people taking a supplement of selenium or vitamin E had a reduced risk of prostate cancer as a direct result of taking the supplement, researchers must compare groups of people who are identical in most respects other than the type of intervention (supplement or placebo, in this case). That way, any differences between the groups would be due to the intervention.What happened if a participant developed prostate cancer while involved in SELECT?

Participants diagnosed with prostate cancer during the study underwent treatment within their community, based upon community treatment standards. These participants continued to be followed by the SELECT study staff. Costs for diagnosis and treatment of prostate problems, prostate cancer, or other medical conditions during the study were charged to the participant in the same way as if he were not part of the trial. A participant's insurance should pay for diagnosis and treatment according to the plan's policies. If the participant has no insurance, social services may be available at the local level to cover costs for diagnosis and treatment.What is selenium? Why study it for prostate cancer prevention?

Selenium is a nonmetallic trace element found in food, especially plant foods such as rice and wheat, seafood, meat, and Brazil nuts. Selenium is an antioxidant and may help control cell damage that could lead to cancer.The Nutritional Prevention of Cancer (NPC) study, first reported in 1996, included 1,312 men and women who had a history of non-melanoma skin cancer. Results of the trial showed that men who took selenium to prevent new non-melanoma skin cancers received no benefit from selenium in preventing that disease. However, approximately 60 percent fewer new cases of prostate cancer were observed among men who had taken selenium for six and one-half years than among men who took placebo (11). In a 2002 follow-up report, the data showed that men who took selenium for more than seven and one-half years had about 52 percent fewer new cases of prostate cancer than men who took placebo (12). This trial was one of the reasons for studying selenium in SELECT.

What dose of selenium was used in SELECT? What risks were involved with taking selenium?

The amount of selenium (provided as l-selenomethionine) was 200 micrograms (μg) daily. Although the initial results of the NPC trial showed an overall decrease in cancer incidence from selenium, a 2003 update reported 17 percent more new non-melanoma skin cancers in the selenium group compared with the placebo group (13). It is not clear how these results would apply to men who did not already have skin cancer when they enrolled in SELECT, or to men who are not at increased risk for skin cancer.Since the start of SELECT, four studies have been published on the effect of selenium on blood glucose and risk of diabetes. Two studies suggested that higher levels of selenium taken from supplements or received naturally were associated with an increased risk of diabetes. One study showed no such association, and one showed that people with higher levels of selenium in their blood had a reduced risk of diabetes (14-17). Starting in early 2007, SWOG specifically asked the SELECT DSMC to review the study data for cases of diabetes because of these findings.

Why didn't the selenium supplement in SELECT prevent prostate cancer?

Researchers don't know why. There are several possible explanations why selenium supplements did not prevent prostate cancer in men on SELECT. These reasons include:- The findings of reduced prostate cancer incidence associated with selenium supplementation in the Nutritional Prevention of cancer (NPC) study may not have been correct and selenium may not affect prostate cancer risk.

- The participants in the NPC study were deficient in selenium compared to the men in SELECT who were not selected because of a likely selenium-deficiency; it may be that selenium only reduces the risk of prostate cancer in selenium-deficient men and not in the general population.

- The supplements given to the men in SELECT may have exceeded the best dose to prevent prostate cancer.

- The formulation of selenium used in the NPC trial (high-selenium yeast) may have been more active than the l-selenomethionine used in SELECT and this may have prevented researchers from seeing a cancer prevention effect. Arguing against this was the fact that early tests showed that, for the selenium yeast, the amount of selenium per dose varied in the NPC trial – this was why this form of selenium was not used in SELECT. Additionally, the inorganic compounds present in the yeast can be toxic and can lead to lower body reserves of selenium. The SELECT biorepository data and samples will help to support research that may answer this question.

What is vitamin E? Why study it for prostate cancer prevention?

Vitamin E is in a wide range of foods, especially vegetables, vegetable oils, nuts, and egg yolks. Vitamin E, like selenium, is an antioxidant, which may help control cell damage that can lead to cancer.In the 1998 study of 29,133 male cigarette smokers in Finland (known as the Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Trial, or ATBC), 32 percent fewer new cases of prostate cancer and 40 percent fewer deaths from prostate cancer were observed among men who took vitamin E in the form of alpha-tocopherol to prevent lung cancer than among men who took a placebo. Some men also took beta-carotene, but neither substance helped prevent lung cancer and beta-carotene did not affect prostate cancer.

How much vitamin E was used in SELECT? What risks were involved?

The amount of vitamin E (provided as dl-alpha-tocopheryl acetate) was 400 milligrams (mg), which is equivalent to 400 IUs per day. This dose of vitamin E may thin the blood somewhat. Vitamin E use has been shown to increase the risk of some cardiovascular conditions, so men with uncontrolled high blood pressure were not eligible to take part in SELECT because taking this much vitamin E might have increased their risk of stroke.In a 2005 study, men and women with vascular disease or diabetes who took 400 IU of vitamin E daily for seven years had a 13 percent increased risk of heart failure compared with participants taking placebo (8). Heart failure is a condition in which the heart's ability to pump blood is weakened. A 2005 analysis of several studies in which people with various medical problems took vitamin E suggested a link between high doses of vitamin E (400 IU or more) and increased mortality (9). In the initial and follow-up analyses of SELECT, there was no difference in the number of cardiovascular events, cardiovascular deaths, or overall deaths between the study groups.

Could men with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) join SELECT?

Men with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), a benign enlargement of the prostate gland, could join SELECT because BPH is not a cancerous or a precancerous condition. In BPH, the prostate grows larger and presses against the urethra and bladder, interfering with the normal flow of urine. More than half of the men in the United States between the ages of 60 and 70, and as many as 90 percent of men between the ages of 70 and 90, have symptoms of BPH.Men were not excluded from SELECT on the basis of taking drugs to treat BPH. Instead, use of these medications was recorded by SELECT investigators.

Could men on SELECT take finasteride? How many men on SELECT used this drug?

Finasteride is a synthetic drug that acts by inhibiting the conversion of testosterone to a more active form. It is used as a treatment for BPH and hair loss. In 2003, the SWOG-coordinated Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT), in which more than 18,000 men took either 5 mg finasteride or a placebo to see if the drug reduced the risk of developing prostate cancer, showed a 25 percent relative reduction in prostate cancer in men taking finasteride (18). Finasteride is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for reducing the risk of developing prostate cancer. Men in SELECT were made aware of these findings and were allowed to take the drug. Overall, about 2.6 percent of men in SELECT had been on the finasteride arm of PCPT, but had stopped taking their study drug, and 4.8 percent of men in SELECT reported use of finasteride for BPH (at the 5 mg/day dose) or for hair growth (at a 1 mg/day dose) during the course of the study.What tests were used to determine eligibility for SELECT? What tests were done during the study?

To be eligible for the SELECT trial, participants had to have a digital rectal exam (DRE) that found no signs of prostate cancer and a total PSA level less than or equal to 4.0 nanograms per milliliter (ng/ml). During the trial, DREs and PSA tests were suggested, but not required, on an annual basis throughout the course of the study. Even though supplement use has stopped in SELECT, the participants are still being asked to report changes in their health. Participants are reminded to discuss the pros and cons of routine screening for prostate cancer with their doctor, but no tests are required during centralized follow-up.Who paid for these tests?

Physician, medical examination, and general clinic costs, including DREs, were charged to the participant in the same way as if he were not part of the trial. These costs may be covered by a participant's health insurance.What other requirements were there for SELECT participants?

Upon enrollment, men were asked to have toenail clippings collected to assess selenium levels in the body because selenium concentrates in fingernails and toenails. Toenails were chosen over fingernails because they take longer to grow and thus contain more history of someone's selenium intake. Blood samples were collected upon enrollment to assess levels of alpha-tocopherol, gamma-tocopherol, selenium, and other dietary nutrients, and again at five years after a man joined the study. These blood samples are stored in the SELECT biorepository for future studies.Also upon enrolling, men filled out a questionnaire about their diet and past supplement use. There was also an annual questionnaire that asked for updates of supplement use. Men did not have to change their diets during this study. Each man was offered a supply of a special daily multivitamin, manufactured by the Perrigo Company, Allegan, Mich., that contained no selenium or vitamin E. Vitamin E, selenium, placebo capsules, and multivitamins were provided free of charge to enrollees. Distribution of the multivitamin ended when SELECT men stopped taking the study supplements.

How much did SELECT cost? Who else funded the study, and why?

NCI is the primary funding agency for SELECT and has provided $129,687,000 to SWOG from 1999 through 2011, with an additional $4.5 million contributed by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), also an agency of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). NCI has also separately funded a substudy to see if the supplements affect the growth of colon polyps. Participants who report having had a colorectal screening procedure while participating in SELECT were asked to sign a consent and release agreement for their medical records. Once all screening procedure reports are collected and reviewed, the researchers will study and report the findings.- In addition, ancillary studies were funded by three other NIH institutes:

- The National Institute on Aging (NIA) provided almost $7 million for the Prevention of Alzheimer's Disease with Vitamin E and Selenium (PREADVISE) trial. This trial is evaluating whether these supplements can help prevent memory loss and dementia, such as that found in Alzheimer's disease. This study closed to accrual in 2009 but PREADVISE participants continuing in centralized follow-up are still being followed.

- The National Eye Institute (NEI) provided almost $2 million for the SELECT Eye Endpoints Study (SEE). Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and cataracts are two leading causes of visual impairment in older Americans. AMD is a disease that affects the central vision, and is the leading cause of visual problems and blindness, with about 25 percent of people over 65 showing some AMD. Cataracts cloud the eye's lens that causes loss of vision. More than 50 percent of adults in the U.S. age 75 and older suffer from visually significant cataracts.

- The National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) has provided more than $3 million for the Respiratory Ancillary Study (RAS). The overall objective of RAS is to understand whether supplements being studied in SELECT have an impact upon the loss of lung function experienced with aging, which is higher in persons who smoke cigarettes. This study closed to accrual in 2007. Sites that were invited to participate had a higher percentage of current and former smokers than the overall SELECT study. (19-20)

Where is more information about SELECT available?

In the United States and Puerto Rico, call the NCI's Cancer Information Service at 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237) for information in English or Spanish. People with TTY equipment can call 1-800-332-8615 for information in English.SWOG (formerly the Southwest Oncology Group) is a network of more than 4,000 researchers at more than 500 institutions that designs and conducts clinical trials to improve the practice of medicine in preventing, detecting, and treating cancer and to enhance the quality of life for cancer survivors. For more information, go to http://www.swog.org –choose the SELECT option. For clinical trials information on SLECT, please go to http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/noteworthy-trials/SELECT/page1. For information about prostate cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment, please go to http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/prostate. For images of the prostate, crystalline and chemical structures of vitamin E, and selenium and vitamin E capsules and to see the original 2001 press release about the opening of the trial, please go to: http://www.cancer.gov/newscenter/pressreleases/2001/select.

For clinical trials information on SELECT, please go to http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/noteworthy-trials/SELECT/page1

For information about prostate cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment, please go to http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/prostate.

For images of the prostate, crystalline and chemical structures of vitamin E, and selenium and vitamin E capsules and to see the original 2001 press release about the opening of the trial, please go to: http://www.cancer.gov/newscenter/pressreleases/2001/select.

References:

(1) Lippman SM, Goodman PJ, Klein EA, et al. Designing the selenium and vitamin E cancer prevention trial. JNCI 2005; 97(2):94-102.

(2) Lippman SM, Klein EA, Goodman PJ, et al. Effect of selenium and vitamin E on risk of prostate cancer and other cancers. JAMA 2009; 301(1). Published online December 9, 2008. Print edition January 2009.

(3) EA Klein, IM Thompson, CM Tangen, et al. Vitamin E and the Risk of Prostate Cancer: Results of The Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA 2011; 306(14) 1549-1556.

(4) Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2008, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2008, based on November 2010 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, 2011.

(5) Yusuf S, Dagenais G, Pogue J, et al. Vitamin E supplementation and cardiovascular events in high risk patients. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342:154-60.

(6) Sesso HD, Buring JE, Christen WG, et al. Vitamins E and C in the prevention of cardiovascular disease in men: the Physicians' Health Study II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008; 300(18):2123-33.

(7) Lee IM, Cook NR, Gaziano JM, et al. Vitamin E in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer: the Women's Health Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005; 294(1):56-65.

(8) Lonn E, Bosch J, Yusuf S, et al. Effects of long-term vitamin E supplementation on cardiovascular events and cancer: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005; 293(11):1338-1347.

(9) Miller ER III, Pastor-Barriuso R, Dalal D, et al. Meta-analysis: High-dosage vitamin E supplementation may increase all-cause mortality. Annals of Internal Medicine 2005; 142(1):37-46.

(10) Heinonen OP, Albanes D, Virtamo J, et al. Prostate cancer and supplementation with alpha-tocopherol and beta-carotene: Incidence and mortality in a controlled trial. JNCI 1998; 90(6):440-446.

(11) Clark LC, Combs GF Jr., Turnbull BW, et al. Effects of selenium supplementation for cancer prevention in patients with carcinoma of the skin. A randomized controlled trial: Nutritional Prevention of Cancer Study Group. JAMA 1996; 276(24):1957-1963.

(12) Duffield-Lillico AJ, Reid ME, Turnbull BW, et al. Baseline characteristics and the effect of selenium supplementation on cancer incidence in a randomized clinical trial: A summary report of the Nutritional Prevention of Cancer Trial. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 2002; 11(7):630-639.

(13) Duffield-Lillico AJ, Slate EH, Reid ME, et al. Selenium supplementation and secondary prevention of nonmelanoma skin cancer in a randomized trial. JNCI 2003; 95(19):1477-1481.

(14) Stranges et al. Effects of Long-Term Use of Selenium Supplements on the Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes. Annals of Internal Medicine; 147:217-233, 2007.

(15) Bleys J et al. Serum Selenium and Diabetes in U.S. Adults. Diabetes Care; 30:829-834, 2007.

(16) Rajpathak et al. Toenail Selenium and Cardiovascular Disease in Men with Diabetes. Journal of the American College of Nutrition; 24: 250-256, 2005.

(17) Czernichowet et al. Antioxidant supplementation does not affect fasting plasma glucose in the Supplementation with Antioxidant Vitamins and Minerals (SU.VI.MAX) study in France: association with dietary intake and plasma concentrations. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition; 84:395-9, 2006.

(18) Thompson IM, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, et al. The influence of finasteride on the development of prostate cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2003; 349:215-224.

(19) Cassano PA, Arnold KB, Guertin K, et al. Effect of vitamin E and selenium on incidence of physician-diagnosed COPD: the selenium and vitamin E cancer Prevention trial (SELECT). American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2010; 181:A6765.

(20) Cassano PA, Guertin KA, Kristal AR, et al. Effect of vitamin E and selenium on rate of decline in FEV 1: the respiratory ancillary study to the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial. American Thoracic Society 2011 annual meeting.

This text may be reproduced or reused freely. Please credit the National Cancer Institute as the source. Any graphics may be owned by the artist or publisher who created them, and permission may be needed for their reuse.