- Home

- Search for Research Summaries, Reviews, and Reports

EHC Component

- EPC Project

Topic Title

- Comparative Effectiveness and Safety of Analgesics for Osteoarthritis–An Update to the 2006 Report

Full Report

- Research Review (Update) Oct. 24, 2011

Related Products for this Topic

- Research Protocol Aug. 5, 2010

- Disposition of Comments Report May 16, 2012

- Clinician Summary Feb. 15, 2012

- Consumer Summary Feb. 15, 2012

- La Guías Sumaria de los Consumidores May 11, 2012

Related Links for this Topic

Executive Summary – Oct. 24, 2011

Analgesics for Osteoarthritis: An Update of the 2006 Comparative Effectiveness Review

Formats

- View PDF (PDF) 167 kB

- Help with Viewers, Players, and Plug-ins

Table of Contents

- Background

- Objectives

- Analytic Framework

- Methods

- Results

- Discussion and Future Research

- Glossary

- References

- Full Report

- For More Copies

Background

Osteoarthritis is a chronic condition involving degeneration of cartilage within the joints. It is the most common form of arthritis and is associated with pain, substantial disability, and reduced quality of life.1 Surveys indicate that 5 to 17 percent of United States (U.S.) adults have symptomatic osteoarthritis of the knee, and 9 percent have symptomatic osteoarthritis of the hip.2 Osteoarthritis is more common with older age. The total costs for arthritis, including osteoarthritis, may be greater than 2 percent of the gross domestic product, with more than half of these costs related to work loss.3, 4

Common oral medications for osteoarthritis include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and acetaminophen. Patients with osteoarthritis also use topical agents, and over-the-counter oral supplements not regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as pharmaceuticals, including glucosamine and chondroitin.5 Opioid medications are also used for selected patients with refractory, chronic pain but are associated with special considerations related to their potential for addiction and abuse and were not included in this review.6-8 Each class of medication or supplement included in this review is associated with a unique balance of risks and benefits. In addition, benefits and harms may vary for individual drugs within a class. Nonpharmacologic interventions (such as physical therapy, weight reduction, and exercise) also help improve pain and functional status in patients with osteoarthritis, but were outside the scope of this review.5

A challenge in treating osteoarthritis is deciding which medications will provide the greatest symptom relief with the least harm. NSAIDs decrease pain, inflammation, and fever by blocking cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes. NSAIDs are thought to exert their effects primarily through blocking different COX isoenzymes, in particular COX-1 and COX-2. COX-1 mediates the mucosal protection of the gastrointestinal mucosa, including protection from acid and platelet aggregation. COX-2 is found throughout the body, including joint and muscle, and mediates effects on pain and inflammation. By blocking COX-2, NSAIDs reduce pain compared with placebo in patients with arthritis,9 low back pain,10 minor injuries, and soft-tissue rheumatism. However, NSAIDs that also block the COX-1 enzyme (also called “nonselective NSAIDs”) can cause gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. The number of deaths in the United States due to use of non-aspirin NSAIDs is not known with certainty. One study estimated the number at 3,200 annually in the 1990s11, though other studies have reported higher estimates. Theoretically, NSAIDs that block only the COX-2 enzyme (also called “coxibs,” “COX-2 selective NSAIDs,” or “selective NSAIDs”) should be safer with regard to GI bleeding, but were found to increase the risk of serious cardiovascular (CV) and other adverse events.

For this report, we defined the terms “selective NSAIDs” or “COX-2 selective NSAIDs” as drugs in the “coxib” class (celecoxib, rofecoxib, valdecoxib, etoricoxib, and lumiracoxib). We defined “partially selective NSAIDs” as other drugs shown to have partial in vitro COX-2 selectivity (meloxicam, etodolac, and nabumetone). However, whether partially selective NSAIDs are truly different from nonselective NSAIDs is unclear because COX-2 selectivity may be lost at higher doses and the effects of in vitro COX-2 selectivity on clinical outcomes are uncertain. Aspirin differs from other NSAIDs because it irreversibly inhibits platelet aggregation, and we considered the salicylic acid derivatives (aspirin and salsalate) a separate subgroup. We defined “non-aspirin, nonselective NSAIDs” or simply “nonselective NSAIDs” as “all other NSAIDs.”

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) funded a comparative effectiveness review (CER) of analgesics for osteoarthritis that was published in 2006.12 Since that time, additional research has become available to better understand the comparative efficacy and safety of oral and topical medications for osteoarthritis, and a study13 commissioned by AHRQ on the need to update CERs assigned high priority to the previous report on analgesics for osteoarthritis based on an assessment of the number of potentially outdated conclusions and ongoing issues related to safety.

Objectives

The purpose of this comparative effectiveness review is to update the previous report12 that assessed the comparative efficacy and safety of nonopioid oral medications (selective and nonselective non-aspirin NSAIDs, aspirin, salsalate, and acetaminophen), over-the-counter supplements (chondroitin and glucosamine), and topical agents (NSAIDs and rubefacients, including capsaicin) for osteoarthritis.

The following Key Questions are the focus of our report:

Key Question 1

What are the comparative benefits and harms of treating osteoarthritis with oral medications or supplements?

- How do these benefits and harms change with dosage and duration of treatment?

The only benefits considered here are improvements in osteoarthritis symptoms. Evidence of harms associated with the use of NSAIDs includes studies of these drugs for treating osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis and for cancer prevention.

Oral agents include:

COX-2 selective NSAIDs:

- celecoxib

Partially selective NSAIDs:

- etodolac

- meloxicam

- nabumetone

Non-aspirin, nonselective NSAIDs:

- diclofenac

- diflunisal

- fenoprofen

- flurbiprofen

- ibuprofen

- indomethacin

- ketoprofen

- ketorolac

- meclofenamate sodium

- mefenamic acid

- naproxen

- oxaprozin

- piroxicam

- sulindac

- tolmetin

Aspirin and salsalate:

- aspirin

- salsalate

Acetaminophen and supplements

- acetaminophen

- chondroitin

- glucosamine

Key Question 2

Do the comparative benefits and harms of oral treatments for osteoarthritis vary for certain demographic and clinical subgroups of patients?

- Demographic subgroups: age, sex, and race

- Coexisting diseases: cardiovascular conditions, such as hypertension, edema, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, peptic ulcer disease, history of previous gastrointestinal bleeding (any cause), renal disease, hepatic disease, diabetes, obesity

- Concomitant medication use: antithrombotics, corticosteroids, antihypertensives, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

Key Question 3

What are the comparative effects of coprescribing H2 receptor antagonists, misoprostol, or proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) on the gastrointestinal harms associated with NSAID use?

Key Question 4

What are the comparative benefits and harms of treating osteoarthritis with oral medications compared with topical preparations, or of different topical medications compared with one another?

For this comparative effectiveness review update, changes have been made to clarify the Key Questions, but these changes do not alter the meaning of each Key Question. Additional coexisting diseases and concomitant medications were included.

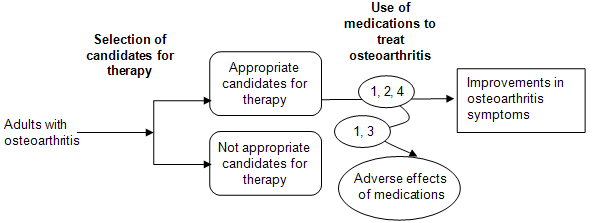

Analytic Framework

The analytic framework (Figure A) depicts the Key Questions within the context of the populations, interventions, comparators, outcomes, timing, and setting (PICOTS). In general, the figure illustrates how the nonopioid oral medications, over-the-counter supplements, and topical agents may result in outcomes such as improvements in osteoarthritis symptoms. Also, adverse events may occur at any point after the treatment is received.

Figure A. Analytic framework

Methods

Input From Stakeholders

The topic for the original 2006 report12 was nominated in a public process. The Key Questions for that report were developed by investigators from the Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) with input from a Technical Expert Panel (TEP), which helped to refine Key Questions, identify important issues, and define parameters for the review of evidence.

For the present report update, AHRQ proposed the same scope and Key Questions to the EPC. The EPC modified the Key Questions and list of included drugs after receiving input from a new TEP convened for this report update. Before participating in official TEP activities for this report, the TEP members disclosed all financial or other potential conflicts of interest with the topic and included drugs. The authors and the AHRQ Task Order Officer reviewed these conflicts and determined whether the disclosed potential conflicts of interest would compromise the report. The final TEP panel consists of individuals who did not have significant conflicts of interest.

Data Sources and Selection

We replicated the comprehensive search of the scientific literature conducted for the original CER, with an updated date range of 2005 to present to identify relevant studies addressing the Key Questions. We searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (through January 2011) the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (through fourth quarter 2010) and Ovid MEDLINE (2005– January 2011). We used relatively broad searches, combining terms for drug names with terms for relevant research designs, limiting to those studies that focused on osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Other sources include selected grey literature provided to the EPC by the Scientific Resource Center librarian, reference lists of review articles, and citations identified by public reviewers of the Key Questions. Pharmaceutical manufacturers were invited to submit scientific information packets, including citations and unpublished data.

We developed criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies based on the Key Questions and the PICOTS approach. Abstracts were reviewed using abstract screening criteria and a two-pass process to identify potentially relevant studies. For the first pass, the abstracts were divided between three investigators. In the second pass, a fourth investigator reviewed all abstracts not selected for inclusion in the first pass. Two investigators then independently reviewed all potentially relevant full text using a more stringent set of criteria for inclusion and exclusion.

As specified in the Key Questions, this review focuses on adults with osteoarthritis. We included studies that evaluate the safety, efficacy, or effectiveness of the included medications in adults with osteoarthritis. We also included studies that report safety in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or who were taking the drug for cancer or Alzheimer’s prevention.

We considered studies that compared any of the oral and topical analgesics listed above to another included drug or placebo. For this report, we categorized NSAIDs as “COX-2 selective,” “partially selective,” salicylic acid derivatives, and “non-aspirin, nonselective” NSAIDs as described on p. ES-5. We excluded evidence on NSAIDs unavailable in the United States, leaving celecoxib as the only COX-2 selective NSAID included in this update.

We included studies that evaluate the safety, efficacy, or effectiveness of the previously mentioned medications. Primary outcomes include improvements in osteoarthritis symptoms and adverse events. Adverse events were evaluated from studies of the drugs used for osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, or cancer treatment. Specific adverse events evaluated include CV [stroke, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, hypertension, and angina]; GI [perforations, symptomatic gastroduodenal ulcers and upper GI bleeding (PUBs), obstructions, and dyspepsia]; renal toxicity; and hepatotoxicity. Other outcomes of interest were quality of life and sudden death.

We defined “benefits” as relief of pain and osteoarthritic symptoms and improved functional status. The main outcome measures for this review were pain, functional status, and discontinuations due to lack of efficacy. Frequently used outcome measures include visual and categorical pain scales.14

We included systematic reviews15 and controlled trials pertinent to the Key Questions. We retrieved and evaluated for inclusion and exclusion any blinded or open, parallel, or crossover randomized controlled trial that compared one included drug to another, another active comparator, or placebo. We also included cohort and case-control studies with at least 1,000 cases or participants that evaluated serious GI and CV endpoints that were inadequately addressed by randomized controlled trials. We excluded non-English language studies unless they were included in an English language systematic review, in which case we relied on the data abstraction and results as reported in the systematic review. All 1,183 citations from these sources and the original report were imported into an electronic database (EndNote X3) and considered for inclusion.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

After studies were selected for inclusion based on the Key Questions and PICOTS, the following data were abstracted and used to assess applicability (see discussion below) (and quality of the study: study design; inclusion and exclusion criteria; population and clinical characteristics (including sex, age, ethnicity, diagnosis, comorbidities, concomitant medications, GI bleeding risk, CV risk); interventions (dose and duration); method of outcome ascertainment, if available; the number of patients randomized relative to the number of patients enrolled, and how similar those patients were to the target population; whether a run in period was used; the funding source; and results for each outcome, focusing on efficacy and safety. We recorded intention-to-treat results if available. Data abstraction for each study was completed by two investigators: the first abstracted the data, and the second reviewed the abstracted data for accuracy and completeness.

We assessed the quality of systematic reviews, randomized trials, and cohort and case control studies based on predefined criteria. We adapted criteria from the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) tool (systematic reviews),16 methods proposed by Downs and Black (observational studies),17 and methods developed by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.18 The criteria used are similar to the approach AHRQ recommended in the draft Methods Reference Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews.19

Individual studies were rated as “good,” “fair” or “poor.”18 Studies rated “good” have the least risk of bias and results are considered valid. Good quality studies include clear descriptions of the population, setting, interventions, and comparison groups; a valid method for allocation of patients to treatment; low dropout rates, and clear reporting of dropouts; appropriate means for preventing bias; appropriate measurement of outcomes, and reporting results.

Studies rated “fair” are susceptible to some bias, but it is not sufficient to invalidate the results. These studies do not meet all the criteria for a rating of good quality because they have some deficiencies, but no flaw is likely to cause major bias. The study may be missing information, making it difficult to assess limitations and potential problems. The “fair” quality category is broad, and studies with this rating vary in their strengths and weaknesses: the results of some fair-quality studies are likely to be valid, while others are only probably valid.

Studies rated “poor” have significant flaws that imply biases of various types that may invalidate the results. They have a serious or “fatal” flaw in design, analysis, or reporting; large amounts of missing information; or discrepancies in reporting. The results of these studies are at least as likely to reflect flaws in the study design as the true difference between the compared drugs. We did not a priori exclude studies rated poor quality, but poor quality studies were considered to be less reliable than higher quality studies when synthesizing the evidence, particularly when discrepancies between studies were present.

Studies could receive one rating for assessment of efficacy and a different rating for assessment of harms. Study quality was assessed by two independent investigators, and disagreements were resolved by consensus.

The applicability of trials and other studies was assessed based on whether the publication adequately described the study population, how similar patients were to the target population in whom the intervention will be applied, whether differences in outcomes were clinically (as well as statistically) significant, and whether the treatment received by the control group was reasonably representative of standard practice.20 We also recorded the funding source and role of the sponsor. We did not assign a rating of applicability (such as “high” or “low”) because applicability may differ based on the user of this report.

We assessed the overall strength of evidence for a body of literature about a particular Key Question in accordance with AHRQ’s Methods Guide for Comparative Effectiveness Reviews,19 based on evidence included in the original CER,12 as well as new evidence identified for this update. We considered the risk of bias (based on the type and quality of studies); the consistency of results within and between study designs; the directness of the evidence linking the intervention and health outcomes; the precision of the estimate of effect (based on the number and size of studies and the confidence intervals for the estimates); strength of association (magnitude of effect); and the possibility for publication bias.

We rated the strength of evidence for each Key Question using the four categories recommended in the AHRQ guide:19 A “high” grade indicates high confidence that the evidence reflects the true effect and that further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect; a “moderate” grade indicates moderate confidence that the evidence reflects the true effect and further research may change our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate; a “low” grade indicates low confidence that the evidence reflects the true effect and further research is likely to change the confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate; an “insufficient” grade indicates evidence either is unavailable or does not permit a conclusion.

Results

Table A provides a summary of the strength of evidence and brief results from this review, based on the evidence included in the original CER and new evidence identified for this update. Overall, we found no clear differences in efficacy of different NSAIDs, but there were potentially important differences in risk of serious harms. Celecoxib may be associated with decreased risk of serious GI events and a number of NSAIDs (selective and nonselective) appear to be associated with increased risk of serious CV risks. Furthermore, individuals are likely to differ in how they prioritize the importance of the various benefits and harms of treatment. Adequate pain relief at the expense of an increase in CV risk, for example, could be an acceptable tradeoff for some patients. Others may consider even a marginal increase in CV risk unacceptable. Factors that should be considered when weighing the potential effects of an analgesic include age (older age being associated with increased risks for bleeding and CV events), comorbid conditions, and concomitant medication use (such as aspirin and anticoagulation medications). As in other medical decisions, choosing the optimal analgesic for an individual with osteoarthritis should always involve careful consideration and thorough discussion of the relevant tradeoffs.

| Key Question | Strength of Evidence | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| CHF = congestive heart failure; CI = confidence interval; CLASS = Celecoxib Long-term Arthritis Safety Study; COX = cyclooxygenase; CV = cardiovascular; FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; GI = gastrointestinal; H2 = histamine 2; HR = hazard ratio; HTN = hypertension; INR = international normalized ratio; NIH = National Institutes of Health; NNT = number needed to treat; NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; OR = odds ratio; PPI = proton pump inhibitor; PUD = peptic ulcer disease; RR = relative risk; VAS = visual analogue scale | ||

| 1. What are the comparative benefits and harms of treating osteoarthritis with oral medications or supplements? | ||

| Benefits: Celecoxib vs. nonselective NSAIDs | High (consistent evidence from many randomized trials) | No clear difference in efficacy for pain relief, or withdrawals due to lack of efficacy. |

| Benefits: Partially selective NSAIDs vs. nonselective NSAIDs | High for meloxicam and etodolac (many randomized trials), low for nabumetone (2 short-term randomized trials) | Meloxicam was associated with no clear difference in efficacy compared to nonselective NSAIDs in 11 head-to-head trials of patients with osteoarthritis, but a systematic review that included trials of patients with osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis found lesser effects on pain compared to nonselective NSAIDs (difference 1.7 points on a 10 point VAS pain scale) and withdrawals due to lack of efficacy (RR 1.5, 95% CI 1.2 to 1.7). Etodolac and nonselective NSAIDs were associated with no statistically significant differences on various efficacy outcomes in several systematic reviews of patients with osteoarthritis, with consistent results reported in 7 trials not included in the systematic reviews. Nabumetone was similar in efficacy to nonselective NSAIDs in two trials. |

| Benefits: Nonselective NSAID vs. nonselective NSAID | High (consistent evidence from many randomized trials) | No difference in efficacy between various non-aspirin, nonselective NSAIDs. |

| Benefits: Aspirin or salsalate vs. other NSAIDs | Low (one randomized trial) | No difference in efficacy between aspirin and salsalate in one head-to-head trial. No trial compared aspirin or salsalate vs. other NSAIDs. |

| GI and CV harms: Celecoxib | High for GI harms vs. nonselective NSAIDs (multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses of mostly short-term trials, multiple observational studies; limited long-term data on serious GI harms) Moderate for CV harms vs. nonselective NSAIDs (multiple systematic review and meta-analyses of longer-term trials; some inconsistency between randomized trials and observational studies) Moderate for CV harms vs. placebo (multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses; mostly from trials of colon polyp prevention) |

GI harms: Celecoxib was associated with a lower risk of ulcer complications (RR 0.23, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.76) and ulcer complications or symptomatic ulcers (RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.21-0.73) compared with nonselective NSAIDs in a systematic review of randomized trials. The systematic review included the pivotal, large, long-term CLASS study, in which celecoxib was superior to diclofenac or ibuprofen for ulcer complications or symptomatic ulcers at 6-month followup (2.1% vs. 3.5%, p=0.02), but not at 12-month followup. However, CLASS found difference in rates of ulcer complications alone at either 6 or 12 months. Other long-term followup data from randomized trials is lacking. A systematic review found celecoxib associated with a lower risk of upper GI bleeding or perforation compared to various nonselective NSAIDs based on 8 observational studies, though confidence interval estimates overlapped in some cases. CV harms: There was no increase in the rate of cardiovascular events with celecoxib vs. ibuprofen or diclofenac in CLASS (0.5% vs. 0.3%). In three systematic reviews of randomized trials, celecoxib was associated with increased risk of cardiovascular events compared to placebo (risk estimates ranged from 1.4 to 1.9). A systematic review of placebo-controlled trials with at least 3 years of planned followup found celecoxib associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events (CV death, myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, or thromembolic event) compared to placebo (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.1-2.3). About 3.7 additional cardiovascular events occurred for every 1,000 patients treated for one year with celecoxib instead of placebo, or 1 additional cardiovascular event for every 270 patients treated for 1 year with celecoxib instead of placebo. The risk was highest in patients prescribed celecoxib 400 mg twice daily compared to celecoxib 200 mg twice daily or 400 mg once daily. Much of the evidence for increased risks comes from two large colon polyp prevention trials. A network analysis of randomized trials and three large observational studies found celecoxib associated with no clear difference in risk of myocardial infarction compared to naproxen, ibuprofen, or diclofenac; a fourth observational study found celecoxib associated with lower risk than ibuprofen or naproxen. 11 of 13 large observational studies found celecoxib associated with no increased risk of myocardial infarction compared to nonuse of NSAIDs. An analysis of all serious adverse events in CLASS based on FDA data found no difference between celecoxib (12/100 patient-years), diclofenac (10/100 patient-years), and ibuprofen (11/100 patient-years). A retrospective cohort study found celecoxib and ibuprofen associated with neutral risk of hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction or GI bleeding compared to use of acetaminophen, but naproxen was associated with increased risk (HR 1.6, 95% CI 1.3 to 1.9). |

| GI and CV harms: Partially selective NSAIDs | GI harms: Moderate for meloxicam and etodolac (fewer trials with methodological shortcomings), low for nabumetone (sparse data) CV harms: Insufficient for all (no trials, few large observational studies) |

GI harms: Meloxicam (primarily at a dose of 7.5 mg/day) was associated with a lower risk of ulcer complications or symptomatic ulcers compared to various nonselective NSAIDs in 6 trials included in a systematic review (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.97), but the difference in risk of ulcer complications alone did not reach statistical significance (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.2). Etodolac (primarily at a dose of 600 mg/day) was associated with a lower risk of ulcer complications or symptomatic ulcer compared to various nonselective NSAIDs in 9 trials included in a systematic review (RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.71), but the difference in risk of ulcer complications alone did not reach statistical significance (RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.12 to 1.2) and the number of events was very small. Evidence was insufficient to make reliable judgments about GI safety of nabumetone. CV harms: Three observational studies found meloxicam associated with no increased risk of serious CV events relative to nonuse. One observational study evaluated etodolac and nabumetone, but estimates were imprecise. |

| GI and CV harms: Nonselective NSAIDs | GI harms: High for naproxen, ibuprofen, and diclofenac (consistent evidence from many trials and observational studies); insufficient for other nonselective NSAIDs (very little evidence) CV harms vs. placebo: Moderate for ibuprofen, diclofenac, and naproxen (almost all evidence from observational studies, few large, long-term controlled trials, indirect evidence); insufficient for other nonselective NSAIDs (very little evidence) CV harms vs. selective NSAIDs: Moderate for ibuprofen, diclofenac, and naproxen (few large, long-term controlled trials, indirect evidence); insufficient for other nonselective NSAIDs (very little evidence) |

GI harms: COX-2 selective NSAIDs as a class were associated with a similar reduction in risk of ulcer complications vs. naproxen (RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.48), ibuprofen (RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.71), and diclofenac (RR 0.31, 95% CI 0.06 to 1.6) in a systematic review of randomized trials. Evidence from randomized trials on comparative risk of serious GI harms associated with other nonselective NSAIDs is sparse. In large observational studies, naproxen was associated with a higher risk of serious GI harms than ibuprofen in 7 studies. Comparative data on GI harms with other nonselective NSAIDs was less consistent. CV harms: An indirect analysis of randomized trials found ibuprofen (RR 1.5, 95% CI 0.96 to 2.4) and diclofenac (RR 1.6, 95% CI 1.1 to 2.4), but not naproxen (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.3) associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction relative to placebo. 1 additional myocardial infarction occurred for about every 300 patients treated for 1 year with celecoxib instead of naproxen. A network analysis of randomized trials reported consistent results with regard to CV events (nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, or cardiovascular death; ibuprofen: RR 2.3, 95% CI 1.1 to 4.9; diclofenac: RR 1.6, 95% CI 0.85 to 3.0 and naproxen: RR 1.2, 955 CI 0.78 to 1.9). An Alzheimer’s disease prevention trial was stopped early due to a trend towards increased risk of myocardial infarction (HR 1.5, 95% CI 0.69 to 3.2) vs. placebo, but did not employ prespecified stopping protocols. In most large observational studies, naproxen was associated with a neutral effect on risk of serious CV events. |

| GI and CV harms: Aspirin | Moderate for GI and CV harms (many trials, but almost exclusively in patients receiving aspirin for cardiovascular disease prevention, usually at lower prophylactic doses) | GI harms: A systematic review of individual patient trial data found aspirin associated with increased risk of major GI and other extracranial bleeding when given for primary prevention of vascular events (RR 1.5, 95% CI 1.3 to 1.8, absolute risk 0.10% vs. 0.07%). Observational studies showed a similar risk of upper GI bleeding with aspirin and non-aspirin, nonselective NSAIDs. CV harms: Aspirin reduced the risk of vascular events in a collaborative meta-analysis of individual patient data from18 randomized controlled trials (0.51% aspirin vs. 0.57% control per year, p=0.0001 for primary prevention and 6.7% vs. 8.2% per year, p<0.0001 for secondary prevention). |

| GI and CV safety: Salsalate | Insufficient | No randomized trial or observational study evaluated risk of serious GI or CV harms with salsalate. |

| Mortality | Moderate (randomized trials with few events, and observational studies) | Large randomized trials and a meta-analysis of trials showed no difference between celecoxib and nonselective NSAIDs, but there were few events. One fair-quality cohort study found nabumetone associated with lower all-cause mortality compared with diclofenac and naproxen, but this finding has not been replicated. |

| HTN, CHF, and impaired renal function | Moderate (randomized trials and observational studies, but analyses limited by incomplete reporting of outcomes) | All NSAIDs are associated with deleterious effects on blood pressure, edema, and renal function. No clear evidence of clinically relevant, consistent differences between celecoxib, partially selective, and nonselective NSAIDs in risk of hypertension, heart failure, or impaired renal function. |

| Hepatotoxicity | High (many trials and large epidemiologic studies) | Several NSAIDs associated with high rates of hepatotoxicity have been removed from the market. A systematic review found clinically significant hepatotoxicity rare with currently available NSAIDs. A systematic review of randomized trials found no difference between celecoxib, diclofenac, ibuprofen, and naproxen in clinical hepatobiliary adverse events, though diclofenac was associated with the highest rate of hepatic laboratory abnormalities (78/1000 patient-years, vs. 16 to 28/1000 patient-years for the other NSAIDs). Another systematic review found diclofenac associated with the highest rate of aminotransferase elevations compared to placebo (3.6% vs. 0.29%, compared to <0.43% with other NSAIDs). |

| Tolerability | High for celecoxib and nonselective NSAIDs, moderate for partially selective NSAIDs (fewer trials with some methodological shortcomings) | The most recent systematic review of randomized trials found celecoxib associated with a lower risk of GI-related adverse events (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.80) and withdrawals due to GI adverse events (RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.56) compared to nonselective NSAIDs, but the difference in risk of any adverse event or withdrawal due to any adverse event did not reach statistical significance). Meloxicam was also associated with decreased risk of any adverse event (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.84 to 0.99), any GI adverse events (RR 0.31, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.39), and withdrawals due to GI adverse events (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.69) compared to nonselective NSAIDs, though there was no difference in risk of withdrawal due to any adverse event. Etodolac was associated with lower risk of any adverse event compared to nonselective NSAIDs (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.99), but there was no difference in risk of GI adverse events, withdrawal due to adverse events, or withdrawal due to GI adverse events. A meta-analysis found nabumetone associated with similar GI adverse events (25% vs. 28%, p=0.007) compared to nonselective NSAIDs. In a systematic review of randomized trials, the only relatively consistent finding regarding the tolerability of different nonselective NSAIDs was that indomethacin was associated with higher rates of toxicity than other NSAIDs (statistical significant unclear). |

| Acetaminophen | Acetaminophen is consistently modestly inferior to NSAIDs for reducing pain and improving function in randomized trials included in multiple systematic reviews. Acetaminophen is superior to NSAIDs for GI side effects (clinical trials data) and GI complications (observational studies). Some observational studies found acetaminophen associated with modest increases in blood pressure or higher risk of renal dysfunction compared to NSAIDs, but results may be susceptible to confounding by indication. One observational study found risk of acute myocardial infarction similar in users of acetaminophen compared to users of NSAIDs. Acetaminophen may cause elevations of liver enzymes at therapeutic doses in healthy persons; comparative hepatic safety has not been evaluated. | |

| Glucosamine and chondroitin | High for glucosamine vs. oral NSAIDs; (consistent evidence from multiple trials) Low for chondroitin vs. oral NSAIDs (one trial) High for glucosamine or chondroitin vs. placebo (consistent evidence from recent, higher quality trials) |

Seven randomized trials showed no clear difference between glucosamine vs. oral NSAIDs for pain or function. One randomized trial showed no difference between chondroitin vs. an oral NSAID. A systematic review including recent, higher quality trials found glucosamine associated with statistically significant but clinically insignificant beneficial effects on pain (-0.4 cm on a 10 cm scale, 95% CI -0.7 to -0.1) and joint space narrowing (-0.2 mm, 95% CI -0.3 to 0.0) compared with placebo. The systematic review reported similar results for chondroitin. A recent large, good-quality NIH-funded trial found the combination of pharmaceutical grade glucosamine hydrochloride and chondroitin sulfate modestly superior to placebo only in an analysis of a small subset of patients with at least moderate baseline pain. Older trials showed a greater benefit with glucosamine or chondroitin, but were characterized by lower quality. For glucosamine, the best results have been reported in trials sponsored by the manufacturer of a European, pharmaceutical grade product (no pharmaceutical-grade glucosamine available in the United States). |

| High for effects of dose and duration (many trials and observational studies with some inconsistency); low for alternative dosage strategies (1 randomized trial) | Higher doses of NSAIDs were associated with greater efficacy for some measures of pain relief, and in some trials with greater withdrawals due to adverse events. A meta-analysis of 41 randomized trials found no clear association between longer duration of therapy with COX-2 selective NSAIDs and increase in the relative risk of CV events. The meta-analysis found higher doses of celecoxib associated with increased risk of cardiovascular events, but most events occurred in the long-term polyp prevention trials. Almost all of the cardiovascular events in trials of celecoxib were reported in long-term trials of colon polyp prevention. Large observational studies showed no association between higher dose and longer duration of nonselective NSAID therapy and increased risk of cardiovascular events. Many observational studies found that risk of GI bleeding increased with higher doses of nonselective NSAIDs, but no clear association with duration of therapy. One small trial found continuous celecoxib slightly more effective than intermittent use on pain and function, and similar rates of withdrawals due to adverse events. No trial was designed to assess serious GI or CV harms associated with intermittent dosing strategies. |

|

| 2. Do the comparative benefits and harms of oral treatments for osteoarthritis vary for certain demographic and clinical subgroups? | ||

| Demographic subgroups including age, sex, and race | Moderate for age (consistent evidence from observational studies) Insufficient for sex and race (most studies included a majority of women, but studies didn’t evaluate whether comparative benefits and harms vary in men and women or in different racial groups) |

The absolute risks of serious GI and CV complications increase with age. Large observational studies that stratified patients by age found no clear evidence of different risk estimates for different age groups. However, because the event rates increases in older patients, even if the relative risk estimates are the same, the absolute event rates are higher. There is insufficient evidence to determine the comparative benefits and harms of different selective and nonselective NSAIDs in men compared to women, or in different racial groups. |

| Preexisting disease including history of previous bleeding due to NSAIDs or peptic ulcer disease; hypertension, edema, ischemic heart disease, and heart failure | Moderate for previous bleeding Moderate for hypertension, edema, ischemic heart disease, heart failure (observational studies and few randomized trials) |

The risk of GI bleeding is higher in patients with prior bleeding. Two trials found high rates of recurrent ulcer bleeding in patients randomized to either celecoxib (4.9% to 8.9% with 200 mg twice daily) or a nonselective NSAID + PPI (6.3%). One trial found celecoxib plus high dose PPI associated with lower risk of bleeding compared with celecoxib alone (0% vs. 8.9%, p=0.0004). A systematic review of randomized trials of celecoxib found risk of CV events doubled in patients at moderate vs. low risk (HR 2.0, 95% CI 1.5 to 2.6) and doubled again in patients at high risk (HR 3.9 for high risk vs. low risk, 95% CI 2.3 to 6.7). Most large observational studies found an association between increased cardiovascular risk and increased risk of cardiovascular events in persons using NSAIDs. Following hospitalization for heart failure, one large observational study found celecoxib and diclofenac associated with a higher risk of death compared to ibuprofen or naproxen, and another large observational study found an increased risk of repeat heart failure admission with indomethacin compared to other nonselective NSAIDs, ibuprofen, acetaminophen, or celecoxib. |

| Concomitant anticoagulant use | Moderate overall: Primarily observational studies | Concomitant use of anticoagulants and nonselective NSAIDs increases the risk of GI bleeding three- to six-fold compared with anticoagulant use without NSAIDs. The risk with concomitant celecoxib is not clear due to conflicting findings among observational studies, but may be increased in older patients. Reliable conclusions about the comparative safety of nonselective, partially selective, and COX-2 selective NSAIDs with concomitant anticoagulants could not be drawn due to small numbers of studies with methodological shortcomings. Warfarin plus low-dose aspirin increased the risk of bleeding compared with warfarin alone in patients with indications for antithrombotic prophylaxis. Acetaminophen can increase INR levels, but effects on bleeding rates have not been studied. |

| Concomitant use of prophylactic-dose aspirin | High for GI harms: Consistent evidence from clinical trials and observational studies Moderate for CV harms: Subgroup analyses from few trials, few observational studies |

Concomitant use of aspirin appears to attenuate or eliminate the GI benefits of selective NSAIDs, resulting in risks similar to nonselective NSAIDs. Concomitant low-dose aspirin increased the rate of endoscopic ulcers by about 6% in patients on celecoxib and those on nonselective NSAIDs in one meta-analysis. Addition of a PPI may reduce the risk of GI harms associated with use of either celecoxib or nonselective NSAIDs plus low-dose aspirin. Evidence regarding the effects of concomitant aspirin use on CV risk associated with selective or nonselective NSAIDs is limited, though three polyp prevention trials of COX-2 selective NSAIDS found that concomitant aspirin use did not attenuate the observed increased risk of CV events. Observational studies did not find increased CV risk with the addition of nonselective NSAIDs as a class to low-dose aspirin. Limited evidence suggests an increased risk of mortality with aspirin and concomitant ibuprofen compared to aspirin alone among high risk patients (HR 1.9, 95% CI 1.3 to 2.9), but studies on effects of ibuprofen added to aspirin on MI risk in average risk patients were inconsistent and did not clearly demonstrate increased risk. |

| 3. What are the comparative effects of coprescribing of H2-antagonists, misoprostol, or PPIs on the gastrointestinal harms associated with NSAID use? | ||

| High: Consistent evidence from good-quality systematic reviews and numerous clinical trials | Misoprostol was the only gastroprotective agent to reduce risk of ulcer complications compared to placebo in patients with average risk of GI bleeding prescribed nonselective NSAIDs, but was also associated with a higher rate of withdrawals due to adverse GI symptoms. Coprescribing of PPIs, misoprostol, and H2-antagonists all reduced the risk of endoscopically detected gastric and duodenal ulcers compared to placebo in patients prescribed a nonselective NSAID. In direct comparisons, coprescribing of PPIs in patients with increased risk of GI bleeding who were prescribed a nonselective NSAID was associated with a lower risk of endoscopically detected duodenal ulcers compared to misoprostol or H2-antagonists, a lower risk of endoscopically detected gastric ulcers compared to H2-antagonists, and a similar risk of endoscopically detected gastric ulcers compared to misoprostol. Coprescribing of misoprostol was associated with a lower risk of endoscopically detected gastric ulcers compared to ranitidine, and a similar reduction in risk of endoscopically detected duodenal ulcers. Compared to placebo, double (full) dose H2-antagonists may be more effective than standard dose for reducing endoscopically detected gastric and duodenal ulcers. Celecoxib alone was associated with fewer decreases in hemoglobin (> 2 g/dl) without overt GI bleeding compared with diclofenac plus a PPI. Celecoxib plus a PPI may reduce the risk of endoscopic ulcers and ulcer complications compared to celecoxib alone in average risk persons. |

|

| 4. What are the comparative benefits and harms of treating osteoarthritis with oral medications compared with topical preparations? | ||

| Topical NSAIDs: efficacy | Moderate (consistent evidence for topical diclofenac from three trials) | Three head-to-head trials found topical diclofenac similar to oral NSAIDs for efficacy in patients with localized osteoarthritis. |

| Topical NSAIDs: safety | Moderate (consistent evidence for topical diclofenac from three trials) | Topical NSAIDs were associated with a lower risk of GI adverse events and higher risk of dermatologic adverse compared to oral NSAIDs. There was insufficient evidence to evaluate comparative risks of GI bleeding or CV events. Other topical NSAIDs evaluated in head-to-head trials have not been FDA approved. |

| Topical salicylates and capsaicin | Insufficient for topical salicylates or capsaicin versus oral NSAIDs (no head-to-head trials) | No head-to-head trials compared topical salicylates or capsaicin to oral NSAIDs for osteoarthritis. |

| Low for topical salicylates or capsaicin versus placebo (some placebo-controlled trials) | Topical salicylates were no better than placebo in two trials of patients with osteoarthritis included in a systematic review, and associated with increased risk of local adverse events when used for any acute or chronic pain condition. Topical capsaicin was superior to placebo (NNT 8.1), but associated with increased local adverse events and withdrawals due to adverse events (13% vs. 3%, RR 4.0, 95% CI 2.3 to 6.8). | |

Discussion and Future Research

This report provides a summary of the evidence on the comparative benefits and harms of oral NSAIDs (celecoxib, partially selective, nonselective, aspirin, and salsalate), acetaminophen, certain over-the-counter supplements (chondroitin and glucosamine), and topical agents (NSAIDs, salicylates, and capsaicin) that are commonly used for pain control and improvement of functional status in patients with osteoarthritis. At this time, no drug or supplement is known to modify the course of disease, though some data suggest potential effects of glucosamine or chondroitin on slowing progression of joint space narrowing.

Major new evidence included in this update include a large trial of celecoxib versus a PPI) plus naproxen and risk of GI bleeding, new placebo-controlled trials of glucosamine and chondroitin, and a new head-to-head trial of topical versus oral diclofenac. Other new evidence in this update includes large observational studies on serious GI and CV harms associated with NSAIDs, and a number of systematic reviews. Like the original CER, a limitation of this update is that studies have not used standardized methods for defining and assessing harms.

As in the original CER, evidence indicates that each of the analgesics evaluated in this report is associated with a unique set of risks and benefits. The role of selective, partially selective, and nonselective oral NSAIDs and alternative agents will continue to evolve as additional information emerges. At this time, although the amount and quality of evidence varies, no currently available analgesic reviewed in this report offers a clear overall advantage compared with the others, which is not surprising given the complex trade-offs between many benefits (pain relief, improved function, improved tolerability, and others) and harms (CV, renal, GI, and others). In addition, individuals are likely to differ in how they prioritize the importance of the various benefits and harms of treatment. Adequate pain relief at the expense of a small increase in CV risk, for example, could be an acceptable tradeoff for many patients. Others may consider even a marginal increase in CV risk unacceptable. Factors that should be considered when weighing the potential effects of an analgesic include age (older age being associated with increased risks for bleeding and CV events), comorbid conditions, and concomitant medication use (such as aspirin and anticoagulation). As in other medical decisions, choosing the optimal analgesic for an individual with osteoarthritis should always involve careful consideration and thorough discussion of the relevant tradeoffs.

The report identified a number of important areas for future research:

- Nearly all of the clinical trials reviewed in this report were “efficacy” trials conducted in ideal settings and selected populations. “Pragmatic” trials that allow flexible dosing or medication switches and other clinical trials of effectiveness would be very valuable for learning the outcomes of different analgesic interventions in real-world settings.

- The CV safety of nonselective NSAIDs has not been adequately assessed in large, long-term clinical trials. Naproxen in particular might have a different CV safety profile from other NSAIDs and should be investigated in long-term, appropriately powered trials.

- Large observational studies assessing the safety of NSAIDs have been helpful for assessing comparative benefits and harms, but have generally had a narrow focus on single adverse events. More observational studies that take a broader view of all serious adverse events would be more helpful for assessing the overall trade-offs between benefits and harms.

- The CV risks and GI benefits associated with different COX-2 selective NSAIDs might vary. Large, long-term trials with active and placebo-controlled arms would be needed to assess the safety and benefits of any new COX-2 selective analgesic.

- Meta-analyses of the risks associated with selective COX-2 inhibitors need to better assess for the effects of dose and duration, as most of the CV harms have only occurred with prolonged use and at higher doses.

- Large, long-term trials of the GI and CV safety associated with full-dose aspirin, salsalate, or acetaminophen compared with non-aspirin NSAIDs or placebo are lacking.

- Trials and observational studies evaluating comparative safety or efficacy should be sufficiently inclusive to evaluate whether effects differ by race or gender.

- Genetic testing could theoretically help predict patients who are at higher risk of CV complications from selective COX-2 inhibitors because of differences in the COX-2 gene promoter or other genes. This remains a promising area of future research.

- The effects of alternative dosing strategies such as intermittent dosing or drug holidays have not been well studied. Studies evaluating the benefits and risks associated with such strategies compared with conventional dosing could help clarify the effects of these alternative dosing strategies. In addition, although there is speculation that once daily versus twice daily dosing of certain COX-2 inhibitors could affect CV risk; this hypothesis has not yet been tested in a clinical trial.

- Most trials showing therapeutic benefits from glucosamine were conducted using pharmaceutical-grade glucosamine not available in the United States and may not be applicable to currently available over-the-counter preparations. Large trials comparing currently available over-the-counter preparations to oral NSAIDs are needed, as these are likely to remain available even if the FDA approves a pharmaceutical grade glucosamine. Additional long-term trials are also required to further evaluate effects of glucosamine on progression of joint space narrowing and to determine the clinical effects of any beneficial effects on radiolographic outcomes.

- Head-to-head trials of topical versus oral NSAIDs have not been large enough to evaluate the risks of serious CV and GI harms. Additional head-to-head trials and large cohort studies may be required to adequately assess serious harms.

Glossary

For this report, we have defined the terms as follows:

- Selective NSAIDs or COX-2 selective NSAIDs: Drugs in the “coxib” class (celecoxib).

- Partially selective NSAIDs: Other drugs shown to have partial in vitro COX-2 selectivity (etodolac, nabumetone, meloxicam).

- Aspirin: Differs from other NSAIDs, because it irreversibly inhibits platelet aggregation; salicylic acid derivatives (aspirin and salsalate) are considered a separate subgroup.

- All other NSAIDs: Non-aspirin, nonselective NSAIDs, or simply nonselective NSAIDs.

References

- Towheed TE, Maxwell L, Anastassiades TP, et al. Impact of musculoskeletal disorders in Canada. Ann Roy Coll Physicians Surg Can 1998;31(5):229-32.

- Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States: Part II. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:26-35.

- Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Dieppe PA, et al. Osteoarthritis: New insights. Part 1: The disease and its risk factors. Ann Intern Med 2000;133:635-46.

- Felson DT, Zhang Y. An update on the epidemiology of knee and hip osteoarthritis with a view to prevention. Arthritis Rheum 1998;41(8):1343-55. PMID: 9704632

- Zhang W, Doherty M, Leeb BF, et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for the management of hand osteoarthritis: report of a Task Force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66(3):377-88. PMID: 17046965

- Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, et al. Clinical Guidelines for the Use of Chronic Opioid Therapy in Chronic Noncancer Pain. J Pain 2009;10(2):113-30.e22.

- Zhang W, Doherty M, Arden N, et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for the management of hip osteoarthritis: report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:669-81.

- Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008;16(2):137-62. PMID: 18279766

- Gotzsche PC. Musculoskeletal disorders. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Clin Evid 2003;(9):1292-300.

- van Tulder MW, Scholten R, Koes BW, Deyo RA. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(3):CD000396. PMID: 00075320-100000000-00426

- Tarone RE, Blot WJ, McLaughlin JK. Nonselective nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and gastrointestinal bleeding: relative and absolute risk estimates from recent epidemiologic studies. Am J Therapeutics 2004;11:17-25.

- Chou R, Helfand M, Peterson K, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of analgesics for osteoarthritis. Comparative Effectiveness Review No.6 (Prepared by the Oregon Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-02-0024.). 2006. PMID: 20704046

- Shekelle P, Newberry S, Maglione M, et al. Assessment of the Need to Update Comparative Effectiveness Reviews Report of an Initial Rapid Program Assessment (2005–2009). 2009. PMID: 21204320

- Strand V, Kelman A. Outcome measures in osteoarthritis: randomized controlled trials. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2004;6:20-30.

- Whitlock EP, Lin JS, Chou R, et al. Using existing systematic reviews in complex systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med 2008;148(10):776-82. PMID: 18490690

- Shea BJ, Hamel C, Wells GA, et al. AMSTAR is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62(10):1013-20. PMID: 19230606

- Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377-84. PMID: 9764259

- Harris RP, Helfand M, Woolf SH, et al. Current methods of the US Preventive Services Task Force: a review of the process. Am J Prev Med 2001;20(3 Suppl):21-35. PMID: 11306229

- Owens DK, Lohr KN, Atkins D, et al. AHRQ series paper 5: grading the strength of a body of evidence when comparing medical interventions—Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Effective Health Care Program. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63(5):513-23. PMID: 19595577

- Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Nissman D, et al. A simple and valid tool distinguished efficacy from effectiveness studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2006;59(10):1040-8. PMID: 16980143

Full Report

This executive summary is part of the following document: Chou R, McDonagh MS, Nakamoto E, Griffin J. Analgesics for Osteoarthritis: An Update of the 2006 Comparative Effectiveness Review. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 38. (Prepared by the Oregon Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. HHSA 290 2007 10057 I) AHRQ Publication No. 11-EHC076-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. October 2011.

For More Copies

For more copies of Analgesics for Osteoarthritis: An Update of the 2006 Comparative Effectiveness Review: Comparative Effectiveness Review Executive Summary No. 38 (AHRQ Pub. No. 11-EHC076-1), please call the AHRQ Clearinghouse at 1-800-358-9295.

Return to Top of Page

E-mail Updates

E-mail Updates