CTSA Training Enables Research on the Effects of Antibiotics on Body Fat

Ilseung Cho, M.D., M.S. (New York University Photo)

A core component of NCATS' Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) program is training, cultivating and sustaining future leaders in the biomedical research workforce. New York University (NYU) School of Medicine's Ilseung Cho, M.D., M.S., attests that his school’s CTSA support has made crucial and ongoing contributions to his professional growth and achievements.

Cho began studying how antibiotics alter the community of bacteria living in the guts of mice as part of his thesis for a CTSA-funded master's degree in clinical investigation, a program open to researchers who have completed residency training in a clinical department at NYU. The research, which began during Cho’s last year of his gastroenterology fellowship, has continued through his transition into a faculty member at NYU.

Researchers have long known that feeding low doses of antibiotics to farm animals makes them grow faster and up to 15 percent larger, but the mechanism behind the effects has remained unclear. Now, thanks to a study supported by a CTSA training grant and by the NYU Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI), Cho and his colleagues have shed light on several of the changes that occur in those animals. Their success hinged on the connections and ideas generated in the setting of mentoring meetings as part of the CTSA training program.

As explained in the August 30 issue of Nature, the researchers tested low doses of antibiotics in mice to learn about the effects on the animals' growth and metabolism. Early in the planning for the project, Cho and his mentor, Martin Blaser, M.D., met with several researchers from the NYU CTSI. During the meeting, one of the senior faculty suggested using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scanning to gauge the animals’ body composition (proportions of fat and lean body mass). The researchers found that although the antibiotic-fed mice weighed the same as the controls (mice not given antibiotics), they had significantly more body fat than control mice.

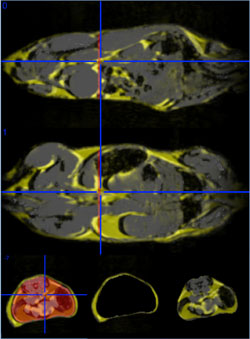

MRI images were used in conjunction with DEXA imaging to determine body composition. The representative MRI images demonstrate the detection of fat. (New York University Photo)

"We didn’t even consider DEXA scanning until NYU CTSI Director Bruce Cronstein, M.D., introduced us to it,” Cho said. “It was serendipity, having the right mentors and the right resources available to you when you need them." Without the DEXA machine, Cho would not have been able to see the key finding about the body composition of mice that were fed antibiotics. "That was a seminal moment for the research," Cho explained.

It turns out that both sets of mice (those getting antibiotics and the controls) had similar numbers — but different types — of microbes in their guts. The microbes in the antibiotic-fed mice transformed food into a form that is more available to the mouse’s digestive system and altered liver metabolism to favor accumulation of body fat.

The study’s findings could have implications for human health. Giving antibiotics to infants might have long-term effects on their metabolism and body composition. More studies are needed to see if shifts in the gut microbiome caused by antibiotics could increase the risk of obesity later in life.

Through the CTSA, the researchers got important advice and training that guided the direction of Cho's research and enabled discovery of the key finding from the study. The work also was supported by NIH's National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Diane Belfer Program in Human Microbial Ecology, the Philip and Janice Levin Foundation, the Michael Saperstein Fellowship, the J. Craig Venter Institute, and the NYU Genome Technology Center.

Cho is continuing his research on antibiotics and the gut ecosystem and still using CTSA resources to accomplish his research goals. He is studying whether giving higher doses of antibiotics for shorter lengths of time — similar to the dosing often used to treat human disease — has the same effect on metabolism. In the long term, he'd like to understand how changes in the gut microbial ecosystem affect diseases he sees in his practice as a gastroenterologist, such as colorectal cancer and inflammatory bowel disease. He now receives further CTSA support via a KL2 award, a program for ongoing training in translational research. "The CTSA provides connections to a broad and varied community of researchers and resources," he said. "It's really catapulted my career."

What's more, Cho is "paying it forward." As he has advanced in his career, he has engaged more and more students on his research team, and the CTSA’s Mentor Development Program has helped him learn how to be an effective mentor and team leader. And that’s key, according to Michael Pillinger, M.D., director of NYU's CTSA education core: "The programs that the NIH so generously supports here are not only helping individuals, but also they are clearly helping us build a culture where those individuals help each other to succeed."

Learn more about NCATS’ CTSA-supported career development and training programs.

Posted December 2012

Social Media Links