Cancer cells

Laboratories across the country soon will change the way they communicate with physicians about the 50 million cervical cancer screening tests performed each year in the United States. The revised system, known as the 2001 Bethesda System and published in the April 24, 2002, issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), conveys laboratory findings that help physicians and their patients decide what to do about the abnormalities found on Pap tests.

BenchMarks interviewed Diane Solomon, M.D., of the Division of Cancer Prevention at the National Cancer Institute (NCI), who is the first author on the JAMA article titled “The 2001 Bethesda System: Terminology for Reporting Results of Cervical Cytology.” Dr. Solomon has worked extensively in the field of cervical cytology and coordinated the development of The Bethesda System in 1988, as well as its revision in 1991 and the current 2001 revision. Dr. Solomon talked to BenchMarks about the changes included in Bethesda 2001 and what the revised system will mean for women and their doctors.

Why is the publication of these two papers considered a “milestone”?

Dr. Solomon: This is a milestone because it’s the first time, to my knowledge, that we have collaborative development of terminology that the lab uses and management guidelines for clinicians based on that terminology. I think that in this collaborative development, each process improved the other – there was cross-fertilization. The involvement of clinicians in the revisions to the Bethesda terminology as well as the participation of pathologists in the development of clinical guidelines will result in better communication between the laboratory and clinicians because both groups are invested in the terminology and the guidelines.

How, specifically, will these publications improve care of patients with Pap test abnormalities?

Dr. Solomon: It will improve the care of women because these guidelines are based on the most up-to-date information we have from research and clinical trials in the area of cervical abnormalities.

A specific example would be in the area of ambiguous test results. We have information from a clinical trial sponsored by the National Cancer Institute that identified a group of women with ambiguous test results that are at higher risk of having an underlying high-grade lesion, or abnormality, that needs to be treated. That finding led to a new term in the new 2001 Bethesda System called “atypical squamous cells cannot exclude HSIL” (ASC-H), which identifies this small number of women.

The guidelines, in turn, recommend that these women be managed differently based on this increased risk. That would be an example of how we have research coming together to inform terminology, and which then becomes the basis for the development of clinical management guidelines.

In addition, the terminology clarifies the communication between the laboratory and the clinician, so that there’s less confusion about what the Pap test findings mean – their clinical significance. For instance, in the previous version of Bethesda, there was a category known as benign cellular changes. This caused a lot of confusion amongst clinicians who really weren’t quite sure whether this was “Negative” or whether this reflected something that really required management – was this woman at increased risk? In the 2001 version of Bethesda, benign changes are more clearly identified as negative for atypical cervical changes. Even if there’s inflammation that’s causing some cellular changes, the findings are categorized as negative. Hopefully this will reduce concern and confusion in communications between the laboratory and clinician.

The fact that this is a uniform terminology that has been adopted by the vast majority of laboratories in the United States means that no matter where a woman is undergoing cervical screening, the terms will be the same.

Are you confident that most laboratories will use the new system?

Dr. Solomon: If past versions of The Bethesda System are any guide, over 90 percent of laboratories in the United States will use some form of the 2001 Bethesda System.

What do you feel is the most significant difference between Bethesda 2001 and the previous Bethesda Systems?

Dr. Solomon: Let me answer that by giving you the reason behind the Bethesda 2001 Workshop and the reason we felt it was necessary to actually revisit the Bethesda terminology.

First, over the past 10 years there has been tremendous development in new technologies for cervical cancer screening. Second, results from studies over the past 10 years have provided a better understanding of cervical abnormalities and their relationship to development of cervical cancer. We wanted to use these findings to improve communication between the pathologist and the clinician.

One example of a significant change in this version of The Bethesda System is the incorporation of the new technology called “liquid-based” collection. Instead of taking a conventional smear that spreads the cell specimen across a glass slide, liquid-based collection involves rinsing or dropping the collection instrument in a vial of liquid fixative. Previous versions of Bethesda required an evaluation of whether the specimen was considered adequate, but criteria were based on the conventional smear and did not address the new technologies. The 2001 Bethesda System incorporates new criteria for evaluating liquid-based specimens.

Another example – and this one reflects our new understanding of cervical abnormalities: There have been a number of studies over the past decade that have identified a subset of women who have ambiguous findings – either squamous atypical changes or glandular atypical changes – who are at higher risk of having an occult, or underdiagnosed, high-grade lesion, who need treatment.

To help identify this subset of women, Bethesda 2001 does two things. First, it eliminates any kind of false assurance to the clinician, by getting rid of the phrases “favor reactive process” or “favor benign process.” Second, it focuses clinicians’ attention on a subset of women with squamous cell changes who are at highest risk of having a lesion that needs treatment. It does this by creating a new category — atypical squamous cells — cannot exclude a high-grade lesion (ASC-H). So these higher-risk cells are now flagged for clinicians – not just in the new terminology but also in the management guidelines. These women are managed differently than the general pool of women who have ambiguous test results.

How do laboratories decide what cells are ASC-H?

Dr. Solomon: Generally, in the cervix, the more cytoplasm you have and the smaller the nucleus, the more benign (negative, normal) the process; tiny nucleus, lots of cytoplasm is benign. We call that low nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio. When the nucleus gets bigger and the cytoplasm gets smaller, we call that a high n:c ratio and those cells cause more concern. Low-grade lesions tend to have an enlarged nucleus, but they have abundant cytoplasm. They’re often easier to see because they’ve got a lot of cytoplasm.

However, highly abnormal cells or high-grade cells can be small, as can perfectly normal cells. When you have small cells with slightly enlarged nuclei, sometimes it’s clear that it’s a very bad cell – and we call it high-grade – but sometimes you can’t quite say whether it’s a reactive normal cell or whether it’s a bad cell. And that’s when we say “atypical squamous cell — cannot exclude a high-grade lesion.” We’re not sure whether it’s coming from a high-grade lesion, or whether it’s coming from something that’s mimicking a high-grade lesion.

How does Bethesda 2001 reflect our current knowledge of the biology of cervical cancer?

Dr. Solomon: We’ve learned a lot over the past 10 to 15 years about the biology of cervical cancer. We know that cervical cancer is clearly related to infection with a virus known as human papillomavirus, or HPV. While HPV is the main cause of cervical cancer, having an HPV infection does not necessarily lead to cervical cancer. In fact, HPV infection is very, very common, while cervical cancer is not. We understand that most people who are infected with HPV have the infection, but only transiently – it goes away on its own. The person’s immune system responds to the presence of the virus and, over the course of a year or so the infection resolves and the virus is no longer found. In some small number of cases the virus persists and cell changes occur that may lead to a precursor lesion to cancer. If not treated such precursor lesions may eventually lead to cancer.

The Bethesda terminology reflects our understanding of the role of HPV and cellular changes in the development of cervical cancer by emphasizing the fact that there is a dichotomy of low-grade lesions and high-grade lesions in the spectrum of squamous cell changes. Low-grade lesions are, by and large, transient infections with HPV that may cause some cellular changes. But in most cases the infection will go away on its own.

Uncommonly, HPV persists and you may have more abnormal cell changes known as a high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, or HSIL. This indicates that the HPV infection has not gone away on its own. This is the lesion that needs to be recognized and treated so that cancer never even develops.

The low-grade and high-grade dichotomy in the spectrum of squamous changes is not something new in Bethesda 2001. It actually was introduced in earlier versions of Bethesda but there has been controversy as to whether this was the proper categorization of the spectrum of squamous changes. What we’ve learned over the past ten years is that yes, the low-grade/high-grade dichotomy is actually the best way to translate what we know about the development of cervical cancer precursors and cervical cancer into terminology for cervical cancer screening. So sometimes we use knowledge to change things and sometimes our new findings actually just reinforce what we had before. In this case, our new knowledge has confirmed the terminology in earlier versions of Bethesda.

Were there concerns about previous Bethesda Systems?

Dr. Solomon: The original Bethesda System introduced a term known as “Atypical Squamous Cells of Undetermined Significance,” which is a very long way of saying that the laboratory is not quite sure what the findings represent. This term has been shortened to an acronym known as ASCUS, which clinicians as well as laboratories have found very frustrating because it’s not quite clear how to manage women who have this ambiguous ASCUS result.

And in fact the National Cancer Institute sponsored a clinical trial of women who have ASCUS, as well as low-grade squamous findings, to ask the question “What is the best way to manage women with these types of test results?” We’ve certainly learned a lot based on ALTS [ASCUS/LSIL Triage Study], which in fact has now informed the development of guidelines for managing women with these findings. So this is a case where the Bethesda terminology really prompted a clinical trial that has provided data that in turn was used in the development of clinical management guidelines.

It’s a frustrating fact for laboratorians, clinicians, doctors, and women that there are limitations to any medical test. No screening test is perfect, and one of the limitations in terms of the Pap test, or cervical cytology, is that the findings are not always crystal clear. There are cell changes that are ambiguous and we have to recognize that. We have to try to reduce that ambiguous category to the lowest possible number, but we also have to acknowledge that that’s one of the limitations of the test. I think the ALTS findings help us deal with that reality of the limitation of cervical screening.

Do you foresee another revision of The Bethesda System?

Dr. Solomon: Not immediately! However, it is true that The Bethesda System is a living document, and that means that it is flexible and can incorporate new developments or new findings based on research. But I think that with this third revision that we have reached a point where we have incorporated all that we currently know about HPV, about the development of cervical precancers and cancers. But I think it’s also important to recognize that should there be new data that comes to light, The Bethesda System is ready to evolve and incorporate new findings.

I know you used the internet to help develop this new system, the new terminology. Tell us how that worked.

Dr. Solomon: For earlier versions of Bethesda, in 1988 and 1991, we had a dozen people or so work on the pre-meeting process and then we held the workshop. It was always an open workshop, but we did not attract more than 50 to 150 people. For the third version of Bethesda, Bethesda 2001, we really wanted to use the Internet to open this up to the cytology community worldwide as well as to other interested individuals who have a stake in cervical cancer screening. We developed an Internet bulletin board site where all of the suggested changes to Bethesda were posted for anyone to review and comment on. The posted comments could be read by others at the bulletin board and individuals could respond to comments that had been left previously or they could leave their opinions about the recommended modifications.

We had over 1,000 individual comments that were posted on the bulletin board. This whole process took many months – leading up to the actual workshop. The workshop itself involved over 400 individuals who represented the spectrum of fields involved in cervical cancer screening. There were nurse practitioners, family practice docs, ob-gyns, pathologists, cytotechnologists, epidemiologists, public health and patient advocates and even a few lawyers present. So the participants truly represented the spectrum of those involved in cervical cancer screening.

What do you see as the next steps related to cervical cancer screening?

Dr. Solomon: We need to continue efforts to reach women who have not been screened. Unscreened women are among those at highest risk for cervical cancer.

We also need to reevaluate screening recommendations for how often women should have Pap tests done, when they should begin having Pap tests done, and if they ever reach a point at which Pap tests are no longer needed. I think one of the key areas that we need to address with regard to screening, is the question of how we incorporate new technologies into new cervical cancer screening recommendations.

What do you see as the next steps in terms of research in cervical cancer screening?

Dr. Solomon: I think one of the most exciting areas in cervical cancer research is the work on developing vaccines against human papillomavirus, or HPV, which we know is the cause of cervical cancer. I think that this is extremely promising and has the potential for having a tremendous impact in terms of women’s health – both in the United States, as well as worldwide.

In the United States we’re fortunate to have a strong cervical cancer screening infrastructure, where women have, by and large, access to Pap testing. But in many parts of the world that lack such an infrastructure, cervical cancer is the number one cause of cancer deaths among women. Development of a vaccine would have a significant impact on reducing deaths due to cervical cancer worldwide.

Animation/video

Anatomy and pap tests

| This movie requires the QuickTime plug-in. If you do not have the plugin, please click here to install. | |

Text Transcript

Anatomy and pap tests

A pap test is performed in this way: The uterus, or womb is located in the woman’s lower abdomen. The lower portion of the womb is called the cervix. The cervix opens into the vagina, which leads to the outside of the body. When the doctor or physician’s assistant does the pap test, a few cells are taken from the cervix.

Reading pap test slides

| This movie requires the QuickTime plug-in. If you do not have the plugin, please click here to install. | |

Text Transcript

Reading pap test slides

A lab technician examines a slide under a microscope.

This clip has no audio.

Audio Clips

- Interview with Diane Solomon, M.D., NCI, on “Reporting Pap Test Results and the 2001 Revision of the Bethesda System”:

( Audio – Length: 02:04 )

Text Transcript

Interview with Diane Solomon, M.D., NCI, on “Reporting Pap Test Results and the 2001 Revision of the Bethesda System”:

Q: Have there been any concerns about previous Bethesda Systems?

Dr. Solomon: The original Bethesda System introduced a term known as “Atypical Squamous Cells of Undetermined Significance,” which is a very long way of saying that the laboratory is not quite sure what the findings represent. This term has been shortened to an acronym known as ASCUS, which clinicians as well as laboratories have found very frustrating because it’s not quite clear how to manage women who have this ambiguous ASCUS result.

And in fact the National Cancer Institute sponsored a clinical trial of women who have ASCUS, as well as low-grade squamous findings, to ask the question “What is the best way to manage women with these types of test results?” We’ve certainly learned a lot based on ALTS [ASCUS/LSIL Triage Study], which in fact has now informed the development of guidelines for managing women with these findings. So this is a case where the Bethesda terminology really prompted a clinical trial that has provided data that in turn was used in the development of clinical management guidelines.

It’s a frustrating fact for laboratorians, clinicians, doctors, and women that there are limitations to any medical test. No screening test is perfect, and one of the limitations in terms of the Pap test, or cervical cytology, is that the findings are not always crystal clear. There are cell changes that are ambiguous and we have to recognize that. We have to try to reduce that ambiguous category to the lowest possible number, but we also have to acknowledge that that’s one of the limitations of the test. I think the ALTS findings help us deal with that reality of the limitation of cervical screening.

- Interview with Diane Solomon, M.D., NCI, on “Reporting Pap Test Results and the 2001 Revision of the Bethesda System”:

( Audio – Length: 01:17 )

Text Transcript

Interview with Diane Solomon, M.D., NCI, on “Reporting Pap Test Results and the 2001 Revision of the Bethesda System”:

Q: What do you see as the next steps in terms of research in cervical cancer screening?

Dr. Solomon: I think one of the most exciting areas in cervical cancer research is the work on developing vaccines against human papillomavirus, or HPV, which we know is the cause of cervical cancer. I think that this is extremely promising and has the potential for having a tremendous impact in terms of women’s health – both in the United States, as well as worldwide.

In the United States we’re fortunate to have a strong cervical cancer screening infrastructure, where women have, by and large, access to Pap testing. But in many parts of the world that lack such an infrastructure, cervical cancer is the number one cause of cancer deaths among women. Development of a vaccine would have a significant impact on reducing deaths due to cervical cancer worldwide.

Photos/Stills

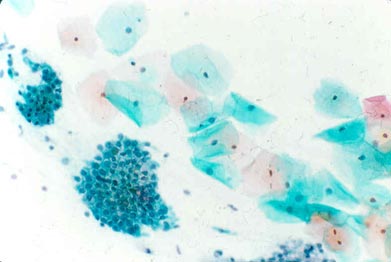

NORMAL:

Squamous cells with small blue nuclei and abundant pink/green cytoplasm. A group of endocervical glandular cells can be seen in the lower left corner with a “honeycomb” arrangement.

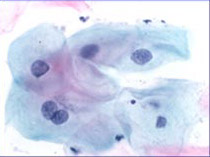

ASC-US:

Squamous cells with some nuclear enlargement but still abundant cytoplasm.

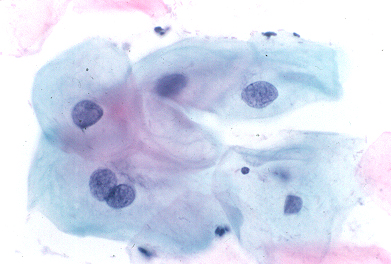

LOW GRADE:

Squamous cells with enlarged dark blue nuclei, occasionally with a cleared ring of cytoplasm.

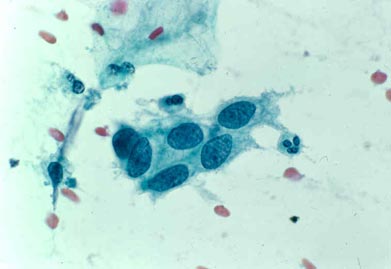

HIGH GRADE:

Very enlarged blue nuclei with less abundant cytoplasm, resulting in a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio.

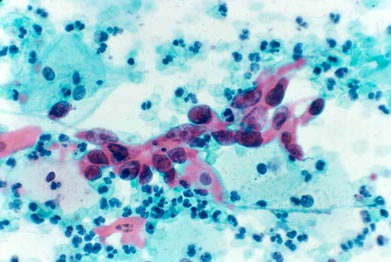

SQUAMOUS CANCER:

Very enlarged nuclei with irregular distribution of nuclear material and nucleoli (red clumps in nuclei); dense spindled pink/orange cytoplasm.

NCI NewsCenter

NCI NewsCenter NCI Budget Data

NCI Budget Data Visuals Online

Visuals Online NCI Fact Sheets

NCI Fact Sheets Understanding Cancer Series

Understanding Cancer Series