- Home

- Search for Research Summaries, Reviews, and Reports

EHC Component

- EPC Project

Topic Title

- Closing the Quality Gap Series: Quality Improvement Measurement of Outcomes for People With Disabilities

Full Report

- Research Review Oct. 15, 2012

Related Products for this Topic

- Research Protocol Aug. 3, 2011

- Disposition of Comments Report Feb. 14, 2013

Closing the Quality Gap Series

- Closing the Quality Gap Series: The Patient-Centered Medical Home

- Closing the Quality Gap Series. Through the Quality Kaleidoscope: Reflections on the Science and Practice of Improving Health Care Quality

- Closing the Quality Gap: Revisiting the State of the Science -- Series Overview

- Closing the Quality Gap Series: Bundled Payment: Effects on Health Care Spending and Quality

- Closing the Quality Gap Series: Revisiting the State of the Science – A Summary

- Closing the Quality Gap Series: Improving Health Care and Palliative Care for Advanced and Serious Illness

- Closing the Quality Gap Series: Prevention of Healthcare-Associated Infections

- Closing the Quality Gap Series: Public Reporting as a Quality Improvement Strategy

- Closing the Quality Gap Series: Medication Adherence Interventions: Comparative Effectiveness

- Closing the Quality Gap Series: Quality Improvement Interventions To Address Health Disparities

Executive Summary – Oct. 15, 2012

Closing the Quality Gap Series: Quality Improvement Measurement of Outcomes for People With Disabilities

Formats

- View PDF (PDF) 520 kB

- Help with Viewers, Players, and Plug-ins

Table of Contents

Introduction

This review is part of a new series of reports, Closing the Quality Gap: Revisiting the State of the Science, commissioned by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The series provides a critical analysis of existing literature on quality improvement strategies and issues for topics identified by the 2003 Institute of Medicine report Priority Areas for National Action: Transforming Health Care Quality.1 As part of its charge to continuously assess progress toward quality and to update the list of priority areas, AHRQ identified people with disabilities as a priority population.

Health care for people with disabilities can present special challenges. For example, medical problems can be exacerbated or complicated by the presence of other medical, psychological, economic, and social problems. Likewise, the management of medical problems can be complicated by disability. Thus, optimal care requires coordination of services from various sectors to maximize the function and quality of life of a person with a disability. Since the care outcomes of function, quality of life, and community integration are interdependent, service coordination may need to span the spectrums of both care and support services (e.g., medical care and schools or social agencies). Coordination of care, with attention to the intersection of medical and social services, is congruent with recent policy attention on integrated care and medical homes.

This review examines how health care outcomes have been assessed for people with disabilities. Our report seeks to improve shared understanding among a broad audience of researchers, clinicians, and policymakers with varied exposure to disability outcomes or quality improvement research. We begin by discussing outcome measurement issues and exploring conceptual frameworks for thinking about measuring outcomes for research and quality improvement efforts. We examine the diverse perspectives that researchers grounded in different fields bring to bear on what and how to measure. As with all frameworks that deal with complex concepts, the categories, paradigms, or classes we present are at best "ideal types" rather than simple designations with clean boundaries. We follow this framework with the Key Questions and summary of the project scope. After outlining methods used, we present the results and discuss the implications.

What Is To Be Measured? Levels of Analysis

Examining outcomes requires a broad understanding of what is appropriate to be measured. The range of outcomes to consider depends in part on the goals for the research or evaluation. The research goals should drive the focus, content, and structure of the optimal measure.

We can address outcomes of care for people with disabilities from several levels. Table A illustrates the relationship between the level of focus and related salient questions or outcomes. We distinguish between interventions directed at a disability from specific interventions directed at a given medical problem for a person with a disability or comprehensive programs designed to integrate medical and social services for people with disabilities. A common approach for integrating services at this level is care coordination. Care coordination is a multidimensional construct that lacks general conceptual consensus; however, it usually relies on broad approaches such as teamwork, information coordination, and care management.2 Care coordination is closely linked to current initiatives to create health care homes.

Within the context of medical interventions, disability may be viewed as a condition, or as a comorbidity or multimorbidity, that complicates care and changes case mix, but for which the same outcomes apply as for people without the disability. Under this premise, disability acts as a confounder that obscures the relationship between treatments and outcomes. In other words, disability exerts a direct effect on the outcome in addition to the effect of the disease.3 One way to address this issue is by treating the disability as a demographic descriptor, as suggested in Healthy People 2010.4 Alternatively, the disability may be considered a mediator that affects either treatment choice or effectiveness. For example, a disability may present special barriers to accessing care, from traveling to the source of care to getting onto an examination table. Likewise, the design of a physical activity regimen for an adult with uncontrolled diabetes will likely differ if the adult has a significant mobility limitation. In that instance, the disability must be analyzed as an interaction variable.

| Level | Common Questions or Outcomes of Interest |

|---|---|

| Note: Bolded levels specify areas examined in this review. ER = emergency room |

|

| Impact of public policy, geographic variation |

|

| Effect of organized programs |

|

| Specific interventions directed at the disability |

|

| Specific interventions directed at a given medical problem, not necessarily related to the disability, for persons with a disability |

|

| Comprehensive programs designed to integrate medical and social services |

|

Determining relevant outcomes and the best way to approach disability depends on how disability is defined and viewed professionally. Further, how well a particular outcome measurement tool "fits" those with and without disabilities depends on a number of factors. Next, we explore both of these themes.

What Is Measured (And Why)

Disability Definitions, Models, and Professional Perspectives

No single definition of disability can apply consistently to the full human lifespan and range of abilities and activities. At a recent AHRQ meeting, nationally recognized experts concluded that a single consensus definition of disability is not feasible or desirable. Instead, they suggested that the definition should be governed by the research issue to which it will be applied.5

In the absence of consensus definitions, broad classifications can be a useful tool. Disabilities are classified variously according to different models of disabilities. The most commonly used models are the medical model, the social model, and the biopsychosocial model.

- The medical model views disabling conditions as a matter of pathophysiology and strives to treat or cure them.6,7

- The social model separates the concepts of disability and health, views the disadvantages experienced by people with disabilities as generated by society, and frames the problem as being the societal response to the disabling condition rather than the person.

- The biopsychosocial model emphasizes the interactions among biological, psychological, social, and cultural factors, and the effects of these interactions on a person's experience of health or illness.8,9

These three models inform and frame the perspectives of those who provide services for, or conduct research about, people with disabilities. Each model supports different treatment or service goals, which in turn drive the issue of which outcomes are salient.

The medical perspective is common among professionals who diagnose and treat people with disabilities via general medical care or care specific to the disabling condition. This model may posit illness as a complication imposed on a person with a disability, or disability as a complication of treating a specific illness. Depending on a provider's specialty, people with disabilities may be the focus of care or comprise only a minority of patients. Curing is an ideal for which to strive. Both the medical and biopsychosocial models may inform the work of these providers to varying degrees based on personal concerns and professional training. Often, interventional research and associated measures within the medical perspective are strongly influenced by the medical model.

The rehabilitation perspective is common among professionals from the medical and allied professional fields (e.g., physiatrists and physical, occupational, or speech therapists). Patients include those with temporary disability due to trauma or illness and those with "stable" disabling conditions. This perspective strives to maximize function and optimize potential opportunities for an individual to participate in life as desired. Here, too, the medical and biopsychosocial models may inform providers' work. However, the biopsychosocial model, with its emphasis on person and environment factors, predominately informs commonly used disablement frameworks.6

The social perspective is common among professionals who (1) study people with disabilities and the effects of disabling conditions; (2) specialize in providing medical care to people with disabilities; or (3) focus on support services, including social work or special education. This perspective acknowledges the appropriateness of medical and rehabilitative efforts specific to a particular person but emphasizes supporting and empowering people who have disabilities to be full participants in their families, communities, and schools, whether or not their disability or related medical conditions can be cured or fixed. Within the social perspective, the biopsychosocial and social models are more influential, as evidenced by the emphasis on healthy adaptation and participation.

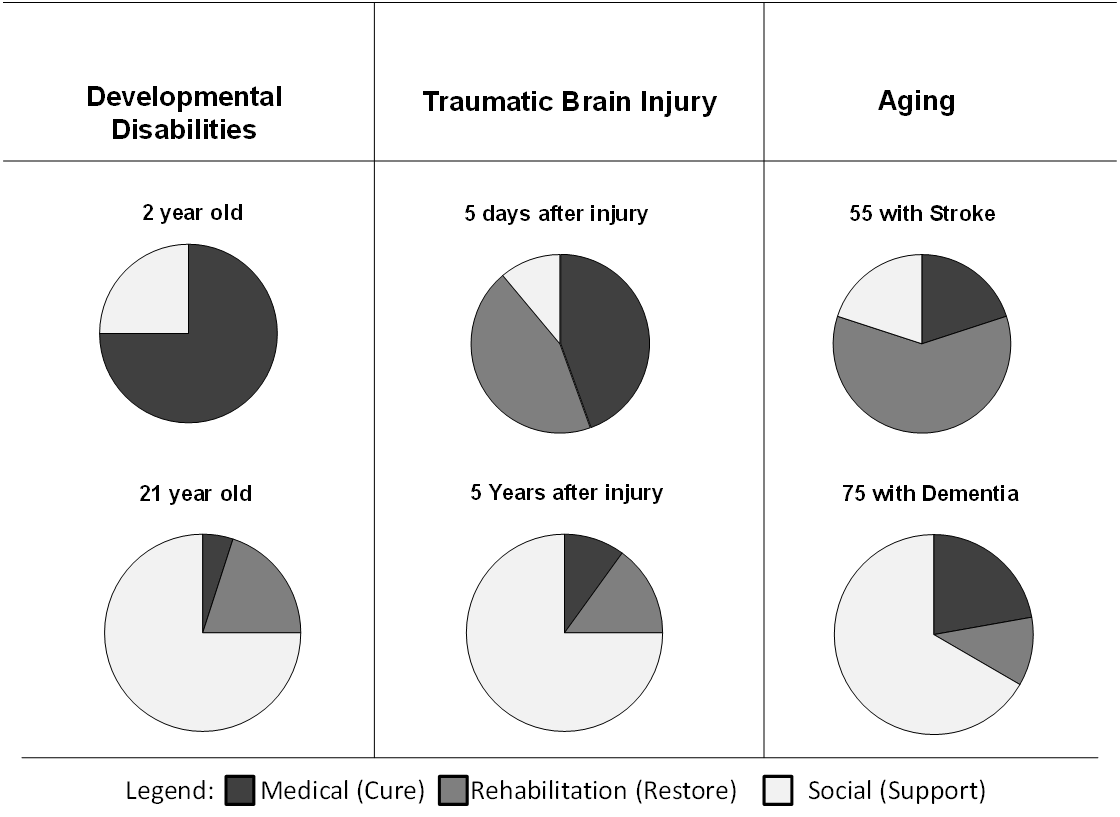

In practice, the "segment size" of each of these three perspectives varies with a person's life course and the etiology of the disability. Three useful categories of disability etiology/timing of onset are: congenital/developmental, acquired (disease or trauma), and aging. Each category holds different implications for treatment and coordination within the medical care system, as well as for determining the most salient outcomes.

For people with developmental and acquired disabilities, care emphasizes support services. Medical care is relevant only to the extent that the individual suffers from problems commonly experienced by people of the same age or from specific disease complications of the underlying condition. At the same time, disabilities may present access barriers to medical care (e.g., getting onto an examination table). Medical practitioners may need special knowledge about how to treat a given disease in the context of the disability. Successful care is generally measured using outcomes related to societal integration.

In contrast, older persons' disabilities are more integrated into a disease framework. It is hard to extricate treating the underlying disease from treating the disability. Perhaps as a result of ageism, achieving societal integration is often viewed as less salient than improving the disease or disability level (or at least slowing decline). Efforts are actively directed at remediation of the problem or its symptoms. The distinction among these etiologies has become more complicated as more people with disabilities survive into old age, bringing with them new perspectives.

As an illustration of these different mindsets, consider the following scenario. A disability activist who has paraplegia and uses a wheelchair is visiting his father, who just recently began using a wheelchair because of a stroke. In response to the nursing home staff's efforts to establish a program of timed toileting and ambulation training for his father, the son responds, "Forget that. Put an external catheter on him and let's get on with life."

This illustration also reveals how people with disabilities—regardless of etiology—prioritize different components at different times in their lives. For example, parents of a child with a newly diagnosed disability often spend considerable time and energy seeking a cure or effective long-term treatment to eliminate or greatly reduce the impact of the diagnosis on the child's life course. In contrast, older children and adults who have lived with their developmental disabilities prioritize getting support needed to live a fully included life, even if the underlying impairment cannot be cured or function fully restored. For people with an acquired disability, an immediate effort to cure or fully restore function through a prolonged period of rehabilitation is followed by a lifetime of getting support needed to live fully included lives. Disabilities that result from degenerative conditions or from aging have a more insidious onset. As a result, those affected by these disabilities will often seek to cure or control the underlying condition (and use rehabilitative support) until it is clear that death is imminent, at which time palliative care is often sought. Figure A illustrates the relative emphasis of the medical, rehabilitation, and social perspectives among different types of disabilities, with traumatic brain injury as one example of acquired disability.

Figure A. Relative emphasis of medical care, rehabilitation, and adaptation for disabilities of different etiology

Note: These are stylized examples to illustrate relative differences.

The life-course perspective introduces another consideration in understanding outcomes. While many people age into disabilities through the advent of illness, some people with disabilities now survive into old age. Although many people who have serious developmental or acquired disabilities have attenuated lifespans, improvements in care have allowed more people with significant disability to reach much older ages, and thus age with a disability.10 While specific consequences vary by disabling condition, a common pattern is that this group may manifest age-related conditions earlier than those without disability.11-16

Finally, the individual's own perspective should not be overlooked. The health goals of people with disabilities do not differ greatly from those of the general population at comparable ages. People with disabilities emphasize their experience of health as distinct from their disabilities.17 This is in keeping with a view of disability as a complicating condition.

The paradigms and perspectives discussed above find traction in how the relevant outcome domains are examined and measured.

Relevant Outcome Domains

Consensus is lacking within the disability research community about the extent to which the outcomes of medical care should be assessed similarly for persons with and without underlying disability, especially developmental and acquired disability. Some view disability as a complicating condition to be included in an appropriate case-mix correction and argue that it does not require different outcome measures from those applied to the general population. Others hold that, in addition to the outcomes measured for the general population, specific outcome domains and measures should be tailored to the populations of interest. They advocate for more individualized approaches that include additional outcomes related to managing disability and preventing secondary conditions. The latter camp argues that quality outcomes for disabling health conditions do not address considerations directly related to disability.5

Outcome domains shared with general populations may require modified methodological approaches for people with disabilities. Measurement instruments determine improvement or lack of improvement in outcomes of interest. The characteristics of measurement tools should be considered, along with how they are used to assess the outcomes of care for people with disabilities.18 Whether or not appropriate outcome domains differ between disabled and nondisabled populations, the methodological approach to assessing outcomes may require accounting for patient characteristics or case mix. Of interest are the independent variables relevant to accurately assessing outcomes.

ICF Outcome Domains

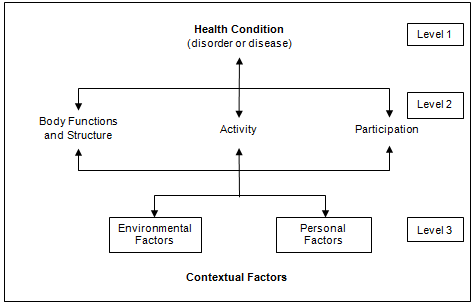

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) was created as a framework to classify and assess function and disability associated with health conditions.19 The initial motivation for the framework was to provide a way to classify the consequences of disease. The framework was later revised to emphasize a positive description of human functioning rather than the negative consequences of disease. The framework (Figure B) attempts to explicitly acknowledge the dynamic nature of disablement, which can fluctuate based on a number of contributing factors across an individual's life course.

The framework identifies three levels of human functioning.

- The first level, health condition, designates functioning at the level of the body or body parts.

- The second level designates functioning at the level of the whole person.

- The third level designates functioning of the whole person in the context of his or her complete environment.

Within the whole-person level are three domains of human functioning: body functions and structure, activity, and participation. The body functions and structure domain involves the physiological functions of the body systems and the anatomical parts of the body. Impairments are problems with the body function or structure that result in a significant loss, defined as "deviations from generally accepted population standards."19 Impairments may be temporary or permanent. A derived version, the ICF-CY, or ICF for Children and Youth, accounts for the developmental nature of children and youth.

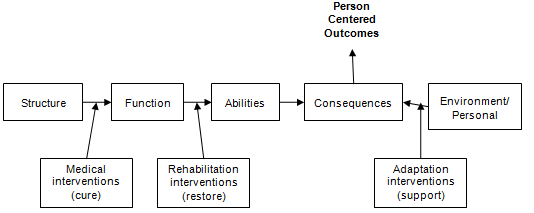

Figure C provides a simplified linear illustration of the ICF to highlight how intervention points may differ for the "treatment" paradigms above. Intermediate measures that assess the immediate effect of an intervention would likely vary based on the intervention point. These interventions ultimately lead to person-centered outcomes, such as quality of life or living independently.

Figure B. Domains of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)

Source: World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. 2001. www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/  .

.

The length and complexity of the ICF highlight the challenge of outcomes conceptualization, categorization, and assessment. The ICF, like the ICD (International Classification of Diseases) codes, involves numerous chapters within each of the body systems and the body function, abilities, participation, and contextual domains, with detailed coding. Some outcomes may be viewed either as intermediate points or endpoints, depending on the research perspective applied. Further, since the ICF is focused on coding function at the person level, it omits system-level outcomes that could be useful for evaluating quality of care or quality improvement initiatives. For example, the ICF would not gather cost and utilization numbers to examine use of second-order services noted in Table A, nor does the ICF encode satisfaction or process measures used to assess the effectiveness of a new program.

Unintended Consequences of Measurement

How we measure outcomes for research or quality improvement can have unintended consequences for people with disabilities. This may be true even for well-designed outcome measures with appropriate characteristics and psychometric properties for a given disabled population. For example, constructs such as the quality-adjusted life year (QALY) or the disability-adjusted life year (DALY) attempt to value health in a way that combines mortality and morbidity. These approaches place an immediate ceiling on the potential benefit achievable by people with a disability, because their baseline status downgrades the QALY score. Basing policy decisions on such measures has substantial implications for people with disabilities.

People with disabilities have also been disadvantaged in participating in research studies because of systematic bias in research fielding and measurement methods. Accommodation and universal design are two approaches promoted for improving access to research participation. Accommodation requires enabling the measurement tools and modes of administration to allow access to people with disabilities. The Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36E (SF-36) is one example of a tool adapted to provide accommodation.20 Universal design strives to develop methods and tools usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without adaptation or specialized design.21 The National Institutes of Health's PROMIS (Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System) initiative is developing computer-assisted data collection tools based on the principles of universal design.22

Figure C. Adapted ICF framework

Note: Adapted from: Colenbrander A. Assessment of functional vision and its rehabilitation. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010 Mar;88(2):163-73. PMID: 20039847.

Key Questions

Our Key Questions (KQs) focus on the quality assessment component of quality improvement. Using the levels-of-analysis framework, we examined outcome measures for medical care and care coordination for people with disabilities, with an emphasis on outcome measures at the level of the individual rather than the population.

KQ1. How are outcomes assessed for people with disabilities living in the community in terms of basic medical service needs?

KQ1a. What general population outcomes have been validated on and/or adjusted to accommodate disabled populations?

KQ1b. What types of modifiers or case-mix adjusters have been used with the general population outcomes to recognize the special circumstances of people with disabilities?

KQ1c. What are key parameters for measuring processes related to basic service care access for people with disabilities?

KQ2. What measures have been used to assess effectiveness of care for people with disabilities living in the community in the context of coordination among health providers?

KQ3. What measures have been used to assess effectiveness of care for people with disabilities living in the community in the context of coordination between community organizations and health providers?

Project Scope

Our scope did not include severe and persistent mental illness as a primary diagnosis, since the disability profile and the cyclical nature of severe and persistent mental illness suggest that some of the processes and outcomes needed for this population would be qualitatively different than those for people with other disabilities. Service settings included outpatient health, home, and community-based services, but not vocational rehabilitation. Medical conditions included basic medical care and secondary conditions common across populations of community-dwelling individuals with disabilities, including:

- Preventive dental care

- Preventive medical care

- Urinary tract infections

- Pressure ulcers

- Diabetes and diabetic complications

- Pneumonia

- Asthma

- Gastroenteritis

- Hypertension

- Obesity

We included measures for both process and patient-centered outcomes. In keeping with the perspective of disability as a complicating condition, we focused on generic outcome measures for the general population or for broad classes of disability. The alternative approach of searching for condition-specific measurement tools was either (1) too resource intensive if all disabilities were included or (2) overly restrictive of the review's applicability if only a few exemplary disability conditions were included. Developing and applying criteria to directly assess outcome measures or mapping the outcome measures directly to the ICF codes was beyond the scope of this review. Instead, we looked for organized collaborations between professional, research, or governmental organizations. We sought collaborations for which formal criteria were developed and used to generate shared knowledge and consensus on core sets of outcome measurements.

With this scope, our report provides sources for outcome material.

Methods

In conducting our searches we used as inclusion criteria:

- Physical, cognitive/intellectual, or developmental disabilities

- All ages

- Outcomes used to evaluate health services

- Outpatient and community settings

Our exclusion criteria included:

- Inpatient settings

- Institutional settings

- Severe mental illness

- Psychotropic medications used in medical/service environments

- Condition-specific outcomes

- Research for specific disability conditions

For KQ1a, we included reviews, compendiums, or suggested outcome sets only if they represented a significant collaborative effort. KQ1b was limited to randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and prospective studies that evaluated the efficacy of a treatment for basic medical service needs and secondary conditions common to people with disabilities, listed above.

Care coordination was operationalized as comprehensive coordination programs consisting of multiple care coordination activities and components. Specifically, we included programs with some kind of purposeful coordination between/among (1) medical providers, (2) medical providers and some community service providers, (3) medical providers and caregivers, and (4) social service groups that included some health component. Studies of single care coordination components were excluded.

We limited the literature to English-language publications after 1990 published in the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia/New Zealand, and the Netherlands, where service delivery settings are more likely to be applicable to the United States.

We searched MEDLINE®, PsychINFO, ERIC, and CIRRIE through March 27, 2012. We hand-searched reference lists of relevant high-quality literature reviews. Two independent reviewers screened search results. Conflicts were resolved by consensus with a third independent investigator.

We searched the gray literature for monographs, white papers, and other high-quality sources of material on measurement tools using the New York Academy of Medicine Grey Literature Report and Web sites such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site.

The included literature was maintained in an EndNote bibliography. Relevant data points were abstracted to standardized Excel spreadsheets. An outcome measurement tool was described in the summary of only one article, unless multiple articles evaluated multiple outcomes with overlap. Qualitative techniques were used to synthesize the literature. We used the ICF as an analytic framework where possible. However, classifying measures by matching items to the detailed ICF checklist was beyond the scope of this review.

Results

A total of 10,189 articles were identified for KQ1. Of these, 241 articles were pulled for full-text review and 15 were included in this review. For KQs 2 and 3, a total of 5,324 care coordination articles were identified, of which 45 were included. A complete reference list is available in the full report.

KQ1a. What general population outcomes have been validated on and/or adjusted to accommodate disabled populations?

Fifteen articles were included for KQ1a. Six articles critically reviewed available outcome measures for given populations and domains. Of these, five were part of a series of papers published in 2000 that used formal criteria to examine the state of outcomes research measurement in rehabilitation. Three studies evaluated the adaptation of general population measures for use in disability populations. Two studies were examples of disability-related outcome measures evaluated for expansion into another disability population (which suggests the possibility that the outcome measure may become more generic). Four articles reported the development of new measures. Table B gives a list of outcome measures either examined or developed by article and domain.23-37 Greater detail is available in the full report.

| Study Domain | Outcome Measure List |

|---|---|

| ADL = activity of daily living; HRQoL = health-related quality of life; ICF = International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; QALY = quality-adjusted life year. | |

| Critical Evaluations of Available Outcome Measures for Given Populations and Outcome Domains | |

| Resnik and Plow, 200923 Participation (9 ICF activities and participation domain chapters: Learning and applying knowledge; General tasks and demands; Communication; Mobility; Self-care; Domestic life; Interpersonal interactions and relationships; Major life areas; Community, social, and civic life) |

|

| Vahle et al., 200024 Depression Symptoms |

|

| Andresen and Meyers, 200025 Generic HRQoL (mixed ICF domains) |

|

| Lollar et al., 200026 Children’s Outcomes (assessed by ICF level) |

|

| Dijkers et al., 200027 Social Outcomes (participation) |

|

| Cohen and Marino, 200028 Functional Status |

|

| Single Studies Evaluating General Population Measures for Use in Disability Populations | |

| Kalpakjian et al., 200529 Body Function |

|

| Burggraaff et al., 201030 Body Function |

|

| Nanda et al., 200331 Health Status – Multiple Domains |

|

| Disability-Related Outcomes Evaluated for Expansion Into Another Disability Population | |

| Bossaert et al., 200932 Environmental |

|

| Bagley et al., 201133 Activity and Performance |

|

| New Measures | |

| Faull and Hills, 200734 Multiple Domains |

|

| Alderman et al., 201135 Multiple Domains |

|

| Petry et al., 200936 Multiple Domains |

|

| King et al., 200737 |

|

Several efforts are underway to use the ICF framework to establish core sets of outcomes for patients with specific chronic conditions. A compendium of critically evaluated rehabilitation outcome measures for community settings was developed through a participatory process to address fragmented outcome measurement use. Further, a rehabilitation outcome database was developed through a collaboration between the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago’s Center for Rehabilitation Outcomes Research and Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine’s Medical Social Sciences Informatics and funded by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (www.rehabmeasures.org  ).

).

KQ1b. What types of modifiers or case-mix adjusters have been used with the general population outcomes?

We found no eligible studies of basic medical needs and secondary conditions that examined a mixed population of disabled and nondisabled participants.

One tangentially related systematic review assessed the effect of exercise interventions as a preventive measure on subjective quality of life for both clinical/disabled and healthy populations. None of the 56 included studies used a mixed population of clinical/disabled and healthy populations; thus comparisons were indirect. The review collected severity information (mild, moderate, severe, chronic stable, frail, end stage) but did not use it in the analysis. Quality-of-life measures included SF-36 (Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form Health Survey), HRQoL (health-related quality of life) visual analog, SIP (Sickness Impact Profile), WHOQOL (World Health Organization Quality of Life Survey), POMS (Profile of Mood States), QWB (Quality of Well-Being Scale), and EuroQoL EQ-5D, among others.

Another tangentially related study addressed associations between the presence of chronic medical needs (chronic diagnoses) and perceived lack of accessibility features in the home according to ADL (activities of daily living) and IADL (instrumental activities of daily living) stage. Subjects were disabled and nondisabled older adults living in the community. The ICF-based stages define five strata for ADL and IADL (measuring the self-care and domestic ICF life chapters). Stage 0 includes people without disabilities and stages I, II, III, and IV represent increasing disability.

KQ1c. What are key parameters for measuring processes related to basic service care access for people with disabilities?

We found no eligible studies of basic medical needs and secondary conditions to address this question. It is possible that the limits of the specific scope of literature, particularly being limited to an illustrative set of medical service needs rather than broader medical coverage, reduced our ability to locate such literature. (See KQs 2 and 3 for more results on care coordination process measures.)

KQs 2 and 3. What measures have been used to assess effectiveness of care for people with disabilities living in the community in the context of coordination among health providers or between community organizations and health providers?

Of the 45 included articles, representing 44 studies (Table C), 7 were RCTs, 9 were prospective observational designs, 3 were retrospective observational designs, 12 were before/after studies, 6 were systematic reviews/guideline studies, and 7 used survey methodology.

| Target Group | Children (0-18) |

Youth in Transition* | Adults (18-64) |

Elderly (65+) |

Mixed | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *Youth in Transition means youth who are being prepared to transition from youth to adult services. | ||||||

| Children–developmental | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Children–acquired | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Children–mixed | 16 | 1 | 17 | |||

| Chronic elderly | 5 | 4 | 9 | |||

| Frail elderly | 7 | 7 | ||||

| Immobile + transition from inpatient | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Medicaid + disabled | 3 | 2 | 5 | |||

| Medicare + disabled + heavy users | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Total | 20 | 1 | 3 | 13 | 7 | 44 |

Two studies of the effects of coordination focused on programs that coordinated primarily among providers. One of these programs was a coordinated followup of infants with prenatally diagnosed giant omphaloceles; the other was the PACE program (Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly), which targeted frail, chronically ill older adults with the goal of keeping them in the community as long as possible.

This study also measured several health care use “outcomes,” but they were not used as outcomes per se. In addition to the primary outcome variable of functional status, several measures of service use were modeled, including short-term nursing home stays, hospitalizations, and day center attendance. The propensity of each studied site to provide those services was then used to model change in functional status for the key analysis of the study.

Nine studies focused on programs primarily concerned with coordination between providers and families, caregivers, social services, etc. Of these, seven served children or young adults (under age 21), one served stroke survivors, and one served frail older adults.

Several domains of measures were found in the studies of care coordination between providers and family/social services (Table D). Perhaps because care coordination programs are quite new, the literature focused primarily on the initial implementation of interventions rather than assessment of the quality of the implementation. We found no measures that assessed changes in process measures of quality over time.

Process measures were sometimes included as proxy outcomes. Participant adherence to treatment, frequency of contacts with physicians, school adherence to child’s treatment plan, and the Measure of Processes of Care scale (MPOC) are examples of these process measures. Of the 34 articles that addressed both types of care coordination, 27 were studies, 2 were expert guidelines, 4 were literature reviews, and 1 was a description of a program.

The most frequently addressed population was children, with 13 articles. The elderly were addressed in 11 articles. Seven articles looked at a mix of ages (although for some of these studies, the vast majority of participants were elderly). Three articles addressed adults (roughly ages 21 to 65).

A total of 109 measurements were abstracted from these 34 articles (Table E).

| Measure Type | Children | Elderly | Mix | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | ||

| Caregiver | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | ||

| Cost and use | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | ||

| Goals | 5 (3) | 5 (3) | ||

| Health and function | 9 (4) | 4 (1) | 2 (1) | 15 (6) |

| Process | 7 (5) | 2 (1) | 9 (6) | |

| Satisfaction | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | ||

| Total | 28 | 5 | 4 | 37 |

| Measure Type | Children (0-18) |

Youth in Transition* | Adults (18-64) |

Elderly (65+) |

Mix | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *Youth in Transition means youth who are being prepared to transition from youth to adult services. | ||||||

| Access | 9 (5) | 9 (5) | ||||

| Provider | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | ||||

| Caregiver | 8 (4) | 8 (5) | 16 (9) | |||

| Cost and use | 7 (7) | 5 (1) | 5 (4) | 11 (4) | 28 (16) | |

| Health and function | 4 (4) | 3 (1) | 14 (6) | 3 (2) | 24 (13) | |

| Process | 5 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 9 (5) | |

| Satisfaction | 4 (1) | 2 (1) | 7 (7) | 13 (9) | ||

| Self-efficacy | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | ||||

| Qualitative feedback | 1(1) | 1 (1) | ||||

| Guideline | 6 (1) | 6 (1) | ||||

| Total | 43 | 11 | 39 | 16 | 109 | |

The National Core Indicators (NCI) is an important collaborative effort among the National Association of State Directors of Developmental Disabilities Services, the Human Services Research Institute, and 28 currently participating States to report a standard set of performance measures. The goal of the collaboration is to develop a core set of measures States can use to manage the quality of developmental disability services, and to allow comparisons among States. A full listing of the measures included in the NCI is provided in the full report.

Discussion

This review found several examples of efforts to critically assess outcome measures for various disabled populations. Formal outcome measure assessment criteria can be leveraged and modified by researchers interested in extending the work to new populations. One example of this is the criteria used by Andresen and colleagues to assess the state of outcome measurement science in rehabilitation.18

Replicable processes exist for participatory collaborative methods for developing consensus around core outcome measurement sets that researchers can replicate or modify. For example, one process that engaged a broad range of stakeholders was Hillier and colleagues’ effort to address fragmented use of outcome measures across rehabilitation in community settings. 38

We have identified a lengthy list of outcome measures that researchers may wish to apply to specific research endeavors. Current efforts offer potential for cross-fertilization. There is also potential for overlap in the important questions and appropriate outcomes for different disability groups. The level of detail necessary for a researcher to choose to successfully use the measures was beyond the scope of this report; however, the cited sources provide a starting point. Much could be gained from developing a core set of outcome measures, as discussed below.

Research Issues and Gaps

Our review clearly demonstrates that quality improvement efforts relevant to disability could greatly benefit from organized databases of critically assessed outcome measures. We identified examples of critical assessments and progress toward working with measurement tool databases. However, much work remains for establishing adequate banks of measures. This is easier said than done.

Synthesizing more knowledge in this area will require building consensus around which outcome measures should form the core of all studies. As with function in general, there are many ways to assess the same underlying problem. Each measure has its own performance characteristics, making it hard to aggregate the already sparse data on how treatments vary across people with different disabilities. Sometimes specific measures or variations are appropriate for ensuring that the right measurement spectrum is achieved for detecting a specific outcome. But the proliferation of measures impedes aggregation. In order to develop practical outcome measures that allow for comparisons across populations, a balance must be struck between granular measurements for specific groups and summary or generic measures for cross-group comparisons. Ultimately, specific group measures and summary or generic measures both serve important purposes.

Professional differences further exacerbate the variation in measurements. Different professions adopt their own standards for measuring the same underlying construct. Sometimes the differences are a matter of scale, driven by different goals. For example, a geriatrician might use a simple ADL that taps six domains, including dressing. The metric would range from “independent” to “doing the task with complete assistance.” Intermediate steps (such as supervision, cueing, and partial assistance) might also be included. In contrast, an occupational therapist would likely break down the task into 26 steps (selecting the clothing, putting it on, fastening the closures, etc.). Primary concerns might be speed and level of performance (e.g., Are the clothes neat? Is the choice appropriate?).

Similarly, an adequate bank of measures for care coordination is needed. One framework for measures for coordinated care for people receiving Medicaid managed care suggests the following categories: patient experience; family experience; family caregiving burden; provider experience; functional status, independence, and community participation; health status; and prevention of secondary conditions.39 To these, we would add measures to evaluate fidelity to the care coordination process and measures that capture access to quality care.

We found very few direct examples of work conducted from the perspective of disability as a complicating condition. The scarcity of literature indicates the early stages of research in this area. The scarcity may also indicate a lack of awareness or unintentional systematic bias against examining disability as a complicating condition rather than the condition of interest itself, the legacy of an outdated separate-but-equal stance toward disabled populations.

How one determines the outcomes most appropriate for a particular research question will be affected by whether one views the disease as a complicating factor for the underlying disability. For example, will an infection exacerbate multiple sclerosis or make it more difficult to manage cerebral palsy? Conversely, does treating pneumonia differ depending on whether the patient has mobility limitations or not? Or does treating a urinary infection differ for a person with quadriplegia compared with someone without disability? Some responses to disability may be akin to ageism. We talk about people developing the problems of aging prematurely, as if they were the problems of aging when they in fact result from disease. Separating the etiology of a problem into normal aging or pathology is already difficult. How much more complicated is it, then, to classify the same problem in a person with an underlying disability?

The continuing presence of research “silos” remains a concern. Multidisciplinary research and coordination of efforts across researchers who focus on medical interventions to cure, on rehabilitation to restore function, and on supportive services for disabilities are crucial. Little has changed in the decade since Meyers and Andresen published the supplemental issue on disability outcomes research in the Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation,20 as evidenced by the current lack of literature.

Ironically, researchers may actually contribute to a problem persistently faced by people with disabilities, which is that they suffer disparities in health care services while at the same time experiencing greater health care needs.40,41 Researchers contribute to this disparity through research designs and practices that either systematically exclude people with disabilities or incompletely capture the outcomes they value. Research silos contribute to this process, as do the context and environment within which researchers work.

The broad scope of the review was a useful endeavor because its findings underscored the need for coordination and collaboration among the three overarching approaches to studying outcomes—medical, rehabilitative, and supportive services. However, the broad sweep also made it difficult to adequately drill down into the literature. Having taken the broad view, future efforts will likely need to go about “eating the elephant” differently. Outcomes for quality medical care (whether treating the disabling condition or treating the disability as a complicating condition) is a vast topic. The trick will be to strike a proper balance between scopes constrained for successful search processes and scopes broad enough to allow for examining similarities and differences in outcome measures. Successful searches will need to be constrained along at least one dimension (e.g., by subpopulation, outcome domain, or outcome level). As the knowledge base around populations and outcomes further develops, mapping the areas of overlap among the three theoretical approaches will become more feasible, as will identifying the areas specific to each theoretical approach.

Limitations

The major limitation of this work is the lack of sensitivity and specificity of the search algorithms. This resulted from the project scope, as well as from the difficulty in creating keyword search terms that adequately capture care coordination and outcome assessment. The literature search was extensive, with carefully designed search algorithms, numerous citations reviewed, and a reasonable coverage of the literature within the scope of the review. However, due to the limitations of search algorithms for diffused literature that necessarily relies on natural language terms rather than MeSH terms, the articles cited should be viewed as a sample of a small and dispersed literature. As stated above, the planned breadth of the review contributed to the search strategy difficulties. Each of the KQs is likely partially answerable if more focused, narrow searches are undertaken in future reviews.

References

- Board on Health Care Services, Institute of Medicine. Priority Areas for National Action: Transforming Health Care Quality. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003.

- McDonald KM, Schultz E, Albin L, Pineda N, Lonhart J, Sundaram V, Smith-Spangler C, Brustrom J, Malcolm E. Care Coordination Atlas Version 3 (Prepared by Stanford University under subcontract to Battelle on Contract No. 290-04-0020). AHRQ Publication No. 11-0023-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. November 2010.

- Stineman MG, Kurichi JE, Kwong PL, et al. Survival analysis in amputees based on physical independence grade achievement. Arch Surg. 2009 Jun;144(6):543-51; discussion 52. PMID: 19528388.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010. Washington: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. www.healthypeople.gov/2010/redirect.aspx?url=/2010/. Accessed April 17, 2012.

- Iezzoni LI. Developing Quality of Care Measures for People with Disabilities: Summary of Expert Meeting. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010. www.ahrq.gov/populations/devqmdis. Accessed January 2010.

- Jette AM. Toward a common language for function, disability, and health. Phys Ther. 2006 May;86(5):726-34. PMID: 16649895.

- Weiner BK. Difficult medical problems: on explanatory models and a pragmatic alternative. Med Hypotheses. 2007;68(3):474-9. PMID: 17055182.

- Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977 Apr 8;196(4286):129-36. PMID: 847460.

- Adler RH. Engel's biopsychosocial model is still relevant today. J Psychosomatic Res. 2009 Dec;67(6):607-11. PMID: 19913665.

- Jensen MP, Molton IR. Preface: aging with a physical disability. Phys Med Rehab Clin N Am. 2010 May;21(2):xv-xvi. PMID: 20494274.

- Strax TE, Luciano L, Dunn AM, et al. Aging and developmental disability. Phys Med Rehab Clin N Am. 2010 May;21(2):419-27. PMID: 20494286.

- Vita AJ, Terry RB, Hubert HB, et al. Aging, health risks, and cumulative disability. N Engl J Med. 1998 Apr 9;338(15):1035-41. PMID: 9535669.

- Widerstrom-Noga E, Finlayson ML. Aging with a disability: physical impairment, pain, and fatigue. Phys Med Rehab Clin N Am. 2010 May;21(2):321-37. PMID: 20494280.

- Carter GT, Weiss MD, Chamberlain JR, et al. Aging with muscular dystrophy: pathophysiology and clinical management. Phys Med Rehab Clin N Am. 2010 May;21(2):429-50. PMID: 20494287.

- Charlifue S, Jha A, Lammertse D. Aging with spinal cord injury. Phys Med Rehab Clin N Am. 2010 May;21(2):383-402. PMID: 20494284.

- Stern M, Sorkin L, Milton K, et al. Aging with multiple sclerosis. Phys Med Rehab Clin N Am. 2010 May;21(2):403-17. PMID: 20494285.

- Powers L. Health and wellness among persons with disabilities. In: RRTC Health and Wellness Consortium, eds. Changing Concepts of Health and Disability: State of the Science Conference and Policy Forum. Portland: Oregon Health and Science University; 2003:73-7.

- Andresen EM. Criteria for assessing the tools of disability outcomes research. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2000 Dec;81(12 Suppl 2):S15-20. PMID: 11128900.

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. 2001. www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/.

- Meyers AR, Andresen EM. Enabling our instruments: accommodation, universal design, and access to participation in research. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2000 Dec;81(12 Suppl 2):S5-9. PMID: 11128904.

- Story MF. Maximizing usability: the principles of universal design. Assistive Technol. 1998;10(1):4-12. PMID: 10181150.

- Harniss M, Amtmann D, Cook D, et al. Considerations for developing interfaces for collecting patient-reported outcomes that allow the inclusion of individuals with disabilities. Med Care. 2007 May;45(5 Suppl 1):S48-54. PMID: 17443119.

- Resnik L, Plow MA. Measuring participation as defined by the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: an evaluation of existing measures. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2009 May;90(5):856-66. PMID: 19406308.

- Vahle VJ, Andresen EM, Hagglund KJ. Depression measures in outcomes research. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2000 Dec;81(12 Suppl 2):S53-62. PMID: 11128905.

- Andresen EM, Meyers AR. Health-related quality of life outcomes measures. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2000 Dec;81(12 Suppl 2):S30-45. PMID: 11128902.

- Lollar DJ, Simeonsson RJ, Nanda U. Measures of outcomes for children and youth. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2000 Dec;81(12 Suppl 2):S46-52. PMID: 11128903.

- Dijkers MP, Whiteneck G, El-Jaroudi R. Measures of social outcomes in disability research. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2000 Dec;81(12 Suppl 2):S63-80. PMID: 11128906.

- Cohen ME, Marino RJ. The tools of disability outcomes research functional status measures. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2000 Dec;81(12 Suppl 2):S21-9. PMID: 11128901.

- Kalpakjian CZ, Toussaint LL, Quint EH, et al. Use of a standardized menopause symptom rating scale in a sample of women with physical disabilities. Menopause. 2005 Jan-Feb;12(1):78-87. PMID: 15668604.

- Burggraaff MC, van Nispen RMA, Hoek S, et al. Feasibility of the Radner Reading Charts in low-vision patients. Graefes Arch Clin Exper Ophthalmol. 2010 Nov;248(11):1631-7. PMID: 20499082.

- Nanda U, McLendon PM, Andresen EM, et al. The SIP68: an abbreviated sickness impact profile for disability outcomes research. Qual Life Res. 2003 Aug;12(5):583-95. PMID: 13677503.

- Bossaert G, Kuppens S, Buntinx W, et al. Usefulness of the Supports Intensity Scale (SIS) for persons with other than intellectual disabilities. Res Devel Disabil. 2009 Nov-Dec;30(6):1306-16. PMID: 19539445.

- Bagley AM, Gorton GE, Bjornson K, et al. Factor- and item-level analyses of the 38-item activities scale for kids-performance. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011 Feb;53(2):161-6. PMID: 20964671.

- Faull K, Hills MD. The QE Health Scale (QEHS): assessment of the clinical reliability and validity of a spiritually based holistic health measure. Disabil Rehab. 2007 May 15;29(9):701-16. PMID: 17453992.

- Alderman N, Wood R, Williams C. The development of the St Andrew's-Swansea Neurobehavioural Outcome Scale: validity and reliability of a new measure of neurobehavioural disability and social handicap. Brain Injury. 2011;25(1):83-100.

- Petry K, Maes B, Vlaskamp C. Measuring the quality of life of people with profound multiple disabilities using the QOL-PMD: first results. Res Devel Disabil. 2009 Nov-Dec;30(6):1394-405. PMID: 19595562.

- King G, Law M, King S, et al. Measuring children's participation in recreation and leisure activities: construct validation of the CAPE and PAC. Child Care Health Devel. 2007 Jan;33(1):28-39. PMID: 17181750.

- Hillier S, Comans T, Sutton M, et al. Development of a participatory process to address fragmented application of outcome measurement for rehabilitation in community settings. [Erratum appears in Disabil Rehab. 2010;32(14):1219]. Disabil Rehab. 2010;32(6):511-20. PMID: 19852700.

- Sofaer S, Kreling B, Carmel M. Coordination of Care for Persons With Disabilities Enrolled in Medicaid Managed Care. A Conceptual Framework To Guide the Development of Measures. Baruch College School of Public Affairs: Office of Disability, Aging, and Long-Term Care Policy. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000.

- Drum C, McClain M, Horner-Johnson W, et al. Health Disparities Chart Book on Disability and Racial and Ethnic Status in the United States. Institute on Disability, University of New Hampshire; 2011.

- Iezzoni L. Eliminating health and health care disparities among the growing population of people with disabilities. Health Aff. 2011;30(10):1947-54.

Full Report

This executive summary is part of the following document: Butler M, Kane RL, Larson S, Jeffery MM, Grove M. Quality Improvement Measurement of Outcomes for People With Disabilities. Closing the Quality Gap: Revisiting the State of the Science. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 208. (Prepared by the Minnesota Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-2007-10064-I.) AHRQ Publication No. 12(13)-E013-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. October 2012. www.effectivehealthcare.gov/reports/final.cfm.

For More Copies

For more copies of Quality Improvement Measurement of Outcomes for People With Disabilities. Closing the Quality Gap: Revisiting the State of the Science: Evidence Report/Technology Assessment Executive Summary No. 208 (AHRQ Pub. No. 12(13)-E013-1), please call the AHRQ Publications Clearinghouse at 1-800-358-9295 or email ahrqpubs@ahrq.gov.

Return to Top of Page

E-mail Updates

E-mail Updates