|

| June 2012 |

|

Objective. This report examines characteristics of admissions to substance abuse treatment in 2009 that reported no use of a primary or secondary drug in the 30 days prior to admission ("abstinent admissions"). To provide a further context for understanding abstinent admissions, the report also presents corresponding information for characteristics of admissions that reported any use in that same period ("nonabstinent admissions"). In addition, the report presents treatment outcomes in 2008 for abstinent and nonabstinent admissions. Methods. The Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS) includes data for more than 1.9 million admissions to substance abuse treatment in 2009 for which a primary substance of abuse was reported at admission. TEDS also includes more than 1.6 million linked admission and discharge records for clients discharged in 2008. Abstinent admissions are defined as those that reported no use of primary or secondary substances in the 30 days prior to admission. Nonabstinent admissions are defined as those that reported use of primary or secondary substances on 1 or more days. Results. The percentage of admissions that were abstinent from primary or secondary substances in the 30 days prior to admission increased from 22.1 percent in 1999 to 25.7 percent in 2009. The supplemental diagnosis item for 2009 indicated that more than 95 percent of abstinent admissions were diagnosed with a substance use or mental health problem, including 90 percent that were diagnosed with a substance use problem. Nearly 70 percent of abstinent admissions in 2009 were referred to treatment either from the criminal justice system or from a substance abuse treatment provider, where the opportunity to engage in substance use may be limited or where there may be increased monitoring for substance use prior to the recorded admission. More than 85 percent of abstinent admissions were admitted to outpatient or intensive outpatient treatment. Abstinent admissions were more likely than nonabstinent admissions to be referred to treatment from the criminal justice system, to be employed, to report income from wages, and they were less likely to be homeless. TEDS discharge data for 2008 indicated that abstinent admissions had higher median lengths of stay in most treatment modalities and were more likely to complete treatment than those that were not abstinent. Conclusions. Despite reports of no use of primary or secondary substances in the 30 days prior to admission, supplemental diagnosis data suggest that the large majority of these admissions needed treatment for substance abuse or mental health conditions. However, data on services at admission, employment, income sources, homelessness, and treatment outcomes suggest that abstinent admissions in TEDS may be admitted to treatment with less severe complications of substance use. Additional increases in the response rates for the supplemental diagnosis item and other supplemental items can strengthen future analyses of characteristics of these admissions. |

A common question about admissions to substance abuse treatment reported in the Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS)—a compilation of data on the characteristics of admissions, primarily from facilities that receive some public funding—concerns the subgroup that self-report no use of a primary or any secondary problem substances in the 30 days prior to admission (subsequently referred to as "abstinent admissions"; however, this term denotes abstinence from reported primary and secondary substances but not necessarily total abstinence from all substances). For example, 28.7 percent of all admissions in 2009 did not report any use of a primary substance for which they were admitted in the 30 days prior to admission. Policymakers and other users of TEDS data may question why individuals are admitted to substance abuse treatment if they reported no use of primary or secondary problem substances in the 30 days prior to admission: If these individuals are being truthful about their abstinence, do they need to receive substance abuse treatment services? Alternatively, are they being untruthful about their recent substance use?

One possible explanation for the sizable proportion of abstinent admissions is that some persons being admitted to substance abuse treatment either deny or underreport recent substance use in an attempt to minimize the magnitude or seriousness of their substance use problem. Studies comparing treatment clients' self-reported use with test results from biological specimens—usually urine—have documented underreporting of recent cocaine or opiate use or frequent use of these substances.1,2,3 However, Wish and colleagues found less underreporting of opiate use than cocaine use at intake. They suggested that persons seeking methadone treatment for heroin or other opiate addiction would have an incentive to report recent opiate use in order to be admitted to treatment. In addition, 87 percent of clients in their study who reported using cocaine on 26 or more days in the 30 days prior to admission and 93 percent of clients who reported this frequency of heroin use had positive urine test results, suggesting a lower likelihood for frequent users to underreport their use at admission.3

Persons referred to treatment from the criminal justice system could be especially reluctant to report recent substance use that might indicate a violation of terms for deferred prosecution, probation, or parole.2,3 Among adult male arrestees in 10 sites in 2010, more than 80 percent of marijuana users (based on positive urine test results) also reported use in interviews, as did 62 percent of methamphetamine users. However, only 45 percent of adult male arrestees whose urine tested positive for cocaine and 37 percent of those with positive urine test results for heroin self-reported use of these substances.4 Although metabolites for most drugs are detectable in urine for only a few days following a person's last use,5 self-reported denial of use in the past 30 days would be inconsistent with a positive urine test result.

Some individuals being admitted to treatment who reported being abstinent could have been infrequent users in the 30 days prior to admission. Although this assumption (or other assumptions of misreporting or underreporting) cannot be proven conclusively from TEDS data, indications of a lower level of problem severity among admissions reporting abstinence could be consistent with infrequent use prior to admission.

Despite the possibility of underreporting of recent substance use among treatment admissions, some admissions that reported being abstinent truly may not have used a primary or secondary problem substance in the 30 days before admission. For example, admissions that are referred from a substance abuse provider may have been abstinent if the admission reflected a transfer from one treatment program to another. In particular, some States reporting to TEDS record transfers to a new level of care within the same treatment episode as new admissions rather than as transfers. Consequently, treating changes within an episode as new admissions, as some States do, could account for some of the observed abstinent admissions.

Although referrals from the criminal justice system were cited as a group that could be motivated to underreport substance use at intake,2,3 some of these criminal justice referrals also could have been truly abstinent. In particular, criminal justice referrals that were recently released from prison or jail could have been abstinent if they began treatment during incarceration. Criminal justice referrals that were on a waiting list to enter treatment also could be motivated to abstain from substance use if their behavior was closely monitored (e.g., through urine testing).

Admissions that truly had not used a primary or secondary substance in the month before admission may differ from nonabstinent admissions in several ways. One possibility is that persons who abstained from primary and secondary substances in the 30 days prior to admission are similar to persons who curtail their substance use without entry into treatment. Especially for persons with alcohol problems, attempts at sustained periods of self-imposed abstinence without entry into specialty substance abuse treatment are not uncommon. For example, nearly one in eight adults who met lifetime but not past year criteria for alcohol dependence and never received substance abuse treatment (including participation in self-help groups or treatment in specialty facilities) did not consume any alcohol in the past year.6 Other literature suggests that persons with greater "social capital" may attempt recovery without entry into formal treatment.7,8,9 For example, one study of persons who had lifetime but not past year alcohol dependence and had never received alcohol treatment identified a cluster of persons that was characterized as having financial or other resources such as having low unemployment, being married, and having more years of education.7 In qualitative interviews from 46 respondents with a history of alcohol or other drug problems who had terminated their level of consumption for at least 1 year and had received no or minimal exposure to formal treatment, all had a high school education or greater, the majority were college graduates, and most were employed in professional occupations or operated their own businesses.9 A second way that abstinent admissions may differ from nonabstinent admissions is that the ability to stay abstinent for an extended period before treatment could indicate a lower level of problem severity.

In light of these considerations, this Data Review presents trend data on admissions in TEDS for 1999 to 2009 that reported being abstinent at admission. By indicating whether reports of abstinence are changing or staying the same over time, these trend data establish a context for further investigations.

This Data Review also examines whether reports of abstinence at admission vary by the primary substance problem at admission. For some substances, persons may seek treatment for problems associated with their substance use but without meeting full criteria for a diagnosis of dependence on that substance. Dependence is characterized by factors such as tolerance to the effects of a substance (e.g., needing to take larger amounts to achieve the same effect), withdrawal symptoms (depending on the substance), and compulsive use (e.g., use more often than intended or inability to keep set limits on use). Among persons who do not meet criteria for a diagnosis of dependence, abuse is characterized by the occurrence of problems at home, work, or school caused by use of the substance; regular substance use associated with situations that might be physically dangerous (e.g., driving under the influence of alcohol or other drugs); repeated trouble with the law because of substance use; or continued use despite substance use having caused problems with family or friends.10 Findings from the 2009 National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) indicated that among persons aged 12 or older with past year dependence or abuse, nearly 90 percent of those with heroin dependence or abuse were dependent, about two thirds of those with cocaine dependence or abuse were dependent, about 60 percent of those with marijuana dependence or abuse were dependent, and 47 percent of those with alcohol dependence or abuse were dependent.11 Consequently, if persons with dependence are less likely to be successful at remaining abstinent for extended periods, reports of abstinence at admission are likely to vary according to the substances for which persons are seeking treatment.

This Data Review also examines the following characteristics of abstinent admissions in the 2009 TEDS data:

Although the focus of this Data Review is on characteristics of abstinent admissions, data also are presented from admissions that reported any use of their primary substance or secondary substances (if applicable) in the past 30 days to identify any special or distinguishing features of abstinent admissions.

The presence of a DSM substance or mental health diagnosis would indicate a need for services even if admissions report abstinence. Admissions also could be truly abstinent if they come from States that record transfers to a new level of care within the same treatment episode as new admissions rather than as transfers. In addition, admissions could be abstinent depending on their source of referral to treatment. Admissions entering treatment from different referral sources could vary in terms of factors that can affect substance use prior to treatment entry such as access to substances or opportunity to use, pretreatment monitoring for any substance use, or whether admissions already were in a treatment setting.

TEDS data on recommended services at admission can provide an indication of problem severity, with less intensive service recommendations (e.g., outpatient) being made for admissions with a lower level of severity. At the other end of the service continuum, persons receiving hospital inpatient detoxification services at admission require detoxification for severe medical complications associated with withdrawal before they can be transitioned to another substance abuse treatment setting. Although persons entering treatment for the first time could present with severe problems related to their substance use, higher numbers of prior treatment admissions indicate more previous episodes of relapse. Similarly, age at admission could be an indicator of problem severity if younger admissions have had less time for their substance use to progress to more severe levels of addiction. Research also emphasizes the importance of early diagnosis and intervention and indicates that the duration of use before starting treatment is related to the length of time it takes treatment admissions to achieve stable abstinence.12

Data on admissions' education level, employment status, sources of income, marital status, and living arrangements (e.g., homelessness) can be used to examine the types of social or other resources that abstinent admissions bring to treatment. In addition, 2008 TEDS discharge data are presented for abstinent and nonabstinent admissions to examine whether abstinence at admission is related to more positive treatment outcomes.

The 2009 TEDS Admissions Data Set was the primary source of data for this Data Review. TEDS is a compilation of data on the demographic characteristics and substance abuse problems of those aged 12 or older who are admitted for substance abuse treatment, primarily from facilities that receive some public funding. TEDS is one component of the Drug and Alcohol Services Information System (DASIS), an integrated data system maintained by the Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (CBHSQ), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

Admissions data are included for more than 1.9 million admissions aged 12 or older to substance abuse treatment in 2009 for which a primary substance problem was reported at admission. Admissions data for 2009 were obtained from 49 States and Puerto Rico; 2009 admissions data for the District of Columbia and Georgia are not included. Further information about the 2009 TEDS is included in the 2009 TEDS report on national admissions to substance abuse treatment services.13 The 1999 to 2009 TEDS admissions data also were used for examining trends in abstinent admissions.

An additional source of data was the 2008 TEDS Discharge Data Set. This data set included more than 1.6 million linked admission and discharge records for clients discharged in 47 States and jurisdictions in 2008.14 (The 2008 discharge data were used because the 2009 Discharge Data Set was not yet available at the time of data analysis.)

Although TEDS includes data for a significant proportion of admissions to substance abuse treatment, it does not include all admissions. Because TEDS is a compilation of facility data from State administrative systems, the scope of facilities included in TEDS is affected by differences in State licensure, certification, and accreditation practices, and disbursement of public funds. In addition, TEDS is an admission-based system. Therefore, TEDS admissions do not represent individuals. For example, an individual admitted to treatment twice within a calendar year would be counted as two admissions.

TEDS Data Elements and DefinitionsThe TEDS Admissions Data System consists of a Minimum Data Set collected by all States and a Supplemental Data Set collected by some States. The Minimum Data Set consists of 19 items. Supplemental Data Set items consist of 15 items that include psychiatric, social, and economic measures.13

The Minimum Data Set includes information about the primary, secondary, and tertiary problem substances and the frequency of use of these substances in the 30 days prior to admission. (Secondary and tertiary substances are subsequently referred to as "secondary substances.") Categories for the frequency of use of primary or secondary substances were (1) no use in the past month, (2) 1-3 times in the past month, (3) 1-2 times in the past week, (4) 3-6 times in the past week, and (5) daily.

Abstinent admissions were defined as those that reported no use of a primary or secondary substance in the 30 days prior to admission based on the reported frequency of use. These admissions were required to report no use of their primary substance in this period. Admissions that reported secondary substances were classified as abstinent if their frequency of use data for secondary substances did not indicate use (which could include reports of no use of secondary substances or situations in which frequency of use data were not recorded), in addition to the report of no use of the primary substance. Admissions were defined as being nonabstinent if they reported use of a primary or secondary substance one or more times in the 30 days prior to admission. As noted previously, admissions that report no use of primary or secondary substances in the past 30 days may have used other substances that were not recorded. For brevity, the 30 days prior to admission is subsequently referred to as the "past 30 days."

TEDS data elements for the measures described in the introduction are listed in Table 1, along with whether the data element is in the Minimum Data Set, Supplemental Data Set, or Discharge Data Set. Table 1 does not show how States or jurisdictions handle transfers or changes in service because this information was not an element of any of these data sets; rather, this measure was derived from information reported to CBHSQ by the States or jurisdictions.

| TEDS Data Element | Minimum Data Set | Supplemental Data Set | Discharge Data Set |

|---|---|---|---|

| DSM Diagnosis* | No | Yes | No |

| Referral Source | Yes | No | No |

| Type of Service at Admission | Yes | No | No |

| Prior Treatment Episodes | Yes | No | No |

| Age at Admission | Yes | No | No |

| Employment Status** | Yes | No | No |

| Highest Grade Completed*** | Yes | No | No |

| Living Arrangements | No | Yes | No |

| Source of Income Support | No | Yes | No |

| Length of Stay | No | No | Yes |

| Treatment Outcome | No | No | Yes |

| NOTE: Handling of changes or transfers is not shown because this is not a TEDS data element. *DSM = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; see American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edition). Washington, DC: Author. **Admissions aged 16 or older. ***Admissions aged 18 or older. |

For the Minimum Data Set item on the source of referral to substance abuse treatment, sources include individuals/self, criminal justice, substance abuse care providers, other health care providers, and other referral sources. Criminal justice referrals in TEDS include clients referred by a court for driving while intoxicated/driving under the influence (DWI/DUI), clients referred in lieu of or for deferred prosecution, clients referred during pretrial release, or clients referred before or after official adjudication. Other sources of referral include school (educational), employers or employee assistance programs, and other community referrals.

The 2008 TEDS Discharge Data included the following outcomes of treatment: (1) completed treatment, (2) transferred, (3) dropped out (i.e., left against professional advice), (4) terminated by action of the facility, and (5) failed to complete treatment for other reasons (e.g., incarcerated, moved, hospitalized). Both treatment completion and transfer to further treatment represent positive conclusions to a treatment episode or component of a treatment episode. Length of stay (LOS) was calculated by subtracting the date of admission from the date of last contact.

Analytic ApproachAdmissions data were subset to those that reported a valid frequency of use for a primary substance, including no use of the primary substance in the past 30 days. Except where noted, data are presented as percentages of all admissions or subgroups of admissions that were reported to TEDS. Denominators for percentages do not include admissions that did not report the characteristic being analyzed (e.g., referral source).

For trend data and 2009 admissions data by primary substance, the denominators for percentages consisted of all admissions (for trend data) or admissions that reported a particular primary substance, with abstinent admissions in the numerator. Because admissions for different primary substances can vary by the source of referral,13 additional analyses were conducted for reports of abstinence among admissions reporting specific primary substances that also controlled for the source of referral. For example, percentages of admissions reporting abstinence were generated in which the denominators consisted of primary alcohol admissions that were criminal justice referrals, primary alcohol admissions that were individual or self-referrals, and so on for admissions reporting a primary alcohol problem.

For remaining analyses characterizing abstinent admissions, abstinent admissions and nonabstinent admissions comprised the relevant denominators, and admissions reporting particular characteristics of interest comprised the numerators. For example, percentages of abstinent admissions were calculated that reported a DSM substance diagnosis, a mental health diagnosis, or some other condition or no diagnosis. Similar percentages were calculated for nonabstinent admissions.

Analyses of Supplemental Data Set items were limited to the States that had a 75 percent or greater response rate for a given item because not all States report these items. However, percentages for these supplemental items in the 2009 TEDS admissions data did not differ appreciably for data that were subset to States that had a 75 percent or greater response rate for an item and for data from all States that reported this item regardless of response rate.

For discharge data, LOS was analyzed according to median lengths of stay rather than mean lengths of stay because the means were sensitive to extreme values. Among all discharges from treatment (i.e., regardless of abstinence or nonabstinence at admission), lengths of stay and detailed reasons for discharge also vary by stay by treatment modality (outpatient, intensive outpatient, short-term residential, and long-term residential).14 Therefore, LOS and discharge data for abstinent and nonabstinent admissions were analyzed for these four modalities.

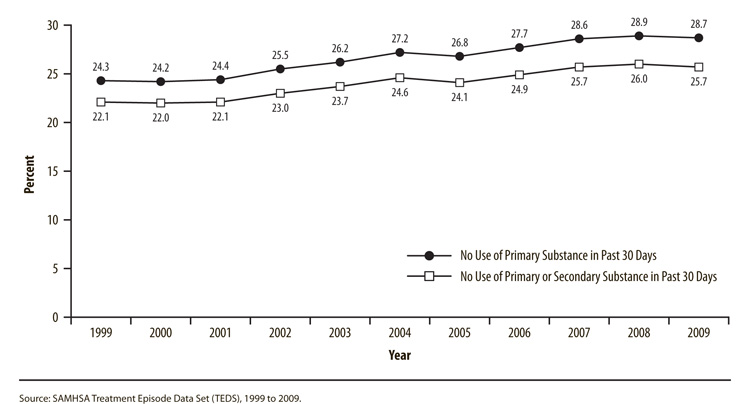

The percentage of admissions reporting that they had not used their primary substance in the past 30 days increased from 24.3 percent in 1999 to 28.7 percent in 2009 (Figure 1). The percentage that was abstinent from a primary substance and any secondary substances in the past 30 days increased from 22.1 percent in 1999 to 25.7 percent in 2009.

|

| Year | No Use of Primary Substance in Past 30 Days |

No Use of Primary or Secondary Substance in Past 30 Days |

|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 24.3% | 22.1% |

| 2000 | 24.2% | 22.0% |

| 2001 | 24.4% | 22.1% |

| 2002 | 25.5% | 23.0% |

| 2003 | 26.2% | 23.7% |

| 2004 | 27.2% | 24.6% |

| 2005 | 26.8% | 24.1% |

| 2006 | 27.7% | 24.9% |

| 2007 | 28.6% | 25.7% |

| 2008 | 28.9% | 26.0% |

| 2009 | 28.7% | 25.7% |

| Source: SAMHSA Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS), 1999 to 2009. |

Percentages of admissions that were abstinent from primary and secondary substances in the past 30 days were lowest among admissions for primary abuse of heroin (13.8 percent) or other opiates (18.0 percent) (Table 2). Percentages were highest among those reporting primary abuse of marijuana (32.8 percent) or methamphetamine (41.7 percent).

| Primary Substance | Any Referral | Criminal Justice | Individual or Self-Referral |

Substance Abuse Provider |

Other Health Care Provider |

Other Referral |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | 25.1% | 38.7% | 12.0% | 22.5% | 12.2% | 22.9% |

| Marijuana | 32.8% | 39.1% | 19.4% | 30.6% | 21.3% | 28.3% |

| Cocaine | 29.8% | 47.2% | 14.9% | 26.5% | 18.8% | 33.1% |

| Heroin | 13.8% | 38.4% | 6.2% | 16.7% | 8.1% | 19.0% |

| Other Opiates | 18.0% | 39.5% | 8.8% | 19.2% | 14.7% | 23.8% |

| Methamphetamine | 41.7% | 49.5% | 24.4% | 43.5% | 26.7% | 41.1% |

| Source: SAMHSA Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS), 2009. |

Among admissions for primary abuse of alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, heroin, other opiates, or methamphetamine, criminal justice referrals were more likely to report abstinence than individual/self-referrals or referrals from health care providers other than substance abuse treatment providers (Table 2). Although only 13.8 percent of primary heroin admissions reported abstinence regardless of referral source, 38.4 percent of those referred from the criminal justice system reported being abstinent in the past 30 days. Nearly 40 percent of admissions for primary abuse of alcohol, marijuana, or other opiates that were referred from the criminal justice system also reported abstinence. More than 45 percent of primary cocaine admissions and nearly half of primary methamphetamine admissions that were referred from the criminal justice system reported abstinence. In contrast, less than 20 percent of individual/self-referrals that reported primary abuse of alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, heroin, or other opiates reported abstinence.

Among most referral sources, primary methamphetamine admissions typically were more likely than admissions for primary abuse of other substances to report abstinence. For example, 24.4 percent of methamphetamine admissions that were individual/self-referrals reported abstinence, compared with 12.0 percent of alcohol admissions, 8.8 percent of other opiate admissions, and 6.2 percent of heroin admissions. More than 40 percent of methamphetamine admissions that were referred from a substance abuse provider reported abstinence, compared with less than 20 percent of admissions for primary abuse of heroin or other opiates.

Diagnoses among Abstinent AdmissionsAmong the 30 States in 2009 that had a 75 percent or greater response rate for the DSM diagnosis item15 (accounting for 41 percent of all treatment admissions), 91.3 percent of abstinent admissions had a DSM substance diagnosis, and 4.9 percent had a mental health diagnosis (Figure 2). Thus, the large majority of abstinent admissions in these States could be considered to need substance abuse or mental health treatment services. These percentages also were comparable to those for nonabstinent admissions, of whom 94.5 percent had a DSM substance diagnosis and 3.0 percent had a mental health diagnosis.

|

| Diagnosis | Abstinent at Admission |

Not Abstinent at Admission |

|---|---|---|

| Any DSM Substance Diagnosis | 91.3% | 94.5% |

| Any Mental Health Diagnosis | 4.9% | 3.0% |

| Other Condition/No Diagnosis | 3.8% | 2.5% |

| NOTE: In 2009, 30 States or jurisdictions had a response rate of 75 percent or greater for this Supplemental Data Set item (AK, AL, AR, AZ, CO, CT, FL, HI, ID, IL, IN, KY, LA, MI, MS, MT, NC, ND, NE, NM, OH, PR, SC, SD, TN, UT, VA, VT, WV, and WY), accounting for 41 percent of admissions. Diagnosis from the fourth edition of the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV)10 is preferred, but use of the third edition or International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes is permissible. Source: SAMHSA Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS), 2009. |

As stated previously, one possible reason that admissions may report abstinence is that some States classify changes in service of individuals who were already in treatment as new admissions. In 2009, 19 States classified changes in service within an episode as new admissions. Admissions from these States—including any duplicate admissions from transfers being classified as new admissions—comprised about 54 percent of the total admissions (excluding Puerto Rico). A total of 27 States accounting for about 44 percent of admissions classified changes in service as a transfer. For an additional three States accounting for about 2 percent of admissions, neither an admission nor a transfer record resulted from a change in service or provider or from a change in service within a provider.16

Although admissions from States that classified changes within an episode as new admissions comprised more than half of the total admissions within the United States, only 48.5 percent of abstinent admissions came from these States. Therefore, States that recorded transfers to a new level of care within the same treatment episode as new admissions did not disproportionately account for the reports of abstinence at admission to treatment.

Referral Sources among Abstinent AdmissionsUnlike the referral source data reported previously for the primary substance of abuse, abstinent admissions comprised the denominators for identifying the referral sources for abstinent admissions. Among abstinent admissions in 2009, 59.4 percent were referred from the criminal justice system (Figure 3). Referrals from substance abuse care providers accounted for an additional 9.0 percent of these admissions. Thus, nearly 70 percent of admissions that reported abstinence were referred from sources where the opportunity to engage in substance use may be limited or where there may be increased monitoring for substance use prior to the recorded admission. In addition, 14.7 percent of abstinent admissions were referred by an individual (including self-referrals).

|

| Treatment Referral Source | Abstinent at Admission |

Not Abstinent at Admission |

|---|---|---|

| Criminal Justice | 59.4% | 30.2% |

| Substance Abuse Treatment Provider | 9.0% | 10.7% |

| Individual | 14.7% | 38.8% |

| Other Health Care Provider | 3.4% | 7.3% |

| Other Referral | 13.4% | 13.1% |

| NOTE: Percentages may not sum to 100 because of rounding. Other sources of referral include school (educational), employers or employee assistance programs, and other community referrals. Source: SAMHSA Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS), 2009. |

Among nonabstinent admissions, individual/self-referrals were the most common referral source (38.8 percent). Criminal justice referrals comprised 30.2 percent of nonabstinent admissions.

Demographic Characteristics among Abstinent AdmissionsMore than 55 percent of abstinent admissions were aged 34 or younger (12 to 17: 8.4 percent; 18 to 24: 20.6 percent; 25 to 34: 28.9 percent) (Table 3). The average age at admission was 33.1 years for abstinent admissions. Admissions aged 34 or younger comprised about half of nonabstinent admissions (12 to 17: 7.2 percent; 18 to 24: 18.5 percent; 25 to 34: 26.2 percent), and the average age at admission for this group was 34.7 years.

| Characteristic | Percentage Abstinent at Admission, Past 30 Days |

Percentage Not Abstinent at Admission, Past 30 Days |

|---|---|---|

| Age Group | ||

| 12 to 17 | 8.4% | 7.2% |

| 18 to 24 | 20.6% | 18.5% |

| 25 to 34 | 28.9% | 26.2% |

| 35 to 44 | 21.6% | 22.9% |

| 45 to 54 | 16.1% | 19.6% |

| 55 or Older | 4.4% | 5.7% |

| Employment Status* | ||

| Employed | 28.3% | 22.2% |

| Unemployed | 37.3% | 39.5% |

| Not in Labor Force | 34.3% | 38.4% |

| Highest Grade Completed** | ||

| Less than High School | 34.6% | 32.6% |

| High School or General Educational Development (GED) Diploma | 43.1% | 42.9% |

| More than High School | 22.3% | 24.5% |

| Living Arrangements*** | ||

| Homeless | 6.4% | 14.9% |

| Dependent Living | 29.7% | 18.9% |

| Independent Living | 63.9% | 66.2% |

| Source of Income Support+ | ||

| Wages/Salary | 32.6% | 25.9% |

| Public Assistance | 8.8% | 7.8% |

| Retirement/Pension | 0.8% | 0.8% |

| Disability | 4.6% | 4.6% |

| Other | 21.1% | 22.8% |

| None | 32.1% | 38.0% |

| NOTE: Percentages may not sum to 100 because of rounding. * Admissions aged 16 or older. ** Admissions aged 18 or older. *** In 2009, 49 States or jurisdictions had a response rate of 75 percent or greater for this Supplemental Data Set item (AK, AL, AR, AZ, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, HI, IA, ID, IL, IN, KS, KY, LA, MA, MD, ME, MI, MN, MO, MS, MT, NC, ND, NE, NH, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OH, OK, OR, PR, RI, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VA, VT, WA, WI, WV, and WY), accounting for 97 percent of admissions. + In 2009, 33 States or jurisdictions had a response rate of 75 percent or greater for this Supplemental Data Set item (AK, AR, CO, DE, FL, HI, IA, ID, IL, KS, KY, LA, ME, MN, MO, MS, MT, ND, NH, NV, NY, OH, OR, PA, PR, RI, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, WV, and WY), accounting for 61 percent of admissions. Source: SAMHSA Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS), 2009. |

Among abstinent admissions, 28.3 percent were employed at admission, 37.3 percent were unemployed, and 34.3 percent were not in the labor force (Table 3). Although the majority of abstinent admissions were unemployed or not in the labor force, they were more likely to be employed than those that were not abstinent (22.2 percent). The most common level of educational attainment among abstinent admissions was completion of high school or receipt of a General Educational Development (GED) diploma (43.1 percent), followed by less than a high school education (34.6 percent) and some education beyond high school (22.3 percent). There was little difference in level of education between abstinent and nonabstinent admissions.

Among the 49 States or jurisdictions (including Puerto Rico) that had a response rate of 75 percent or greater for the supplemental living arrangements measure (accounting for 97 percent of all admissions in 2009), 63.9 percent of abstinent admissions reported being in an independent living situation at admission, 29.7 percent were in a dependent living situation, and 6.4 percent were homeless (Table 3); TEDS defines clients in dependent living as those living in a supervised setting such as a residential institution, halfway house, or group home, and children (aged 17 or younger) living with parents, relatives, or guardians, or in foster care. Because admissions in dependent living situations include those aged 17 or younger that were living with parents or other adult guardians, data on living arrangements also were run separately for admissions aged 18 or older. Among adult admissions, 25.4 percent of those that were abstinent at admission reported that they were in dependent living situations.

Among nonabstinent admissions, 66.2 percent were in independent living situations, 18.9 percent were in dependent living situations, and 14.9 percent were homeless at admission. Thus, admissions in independent living situations comprised the majority of abstinent and nonabstinent admissions. However, abstinent admissions were less likely than those that were not abstinent to report that they were homeless, and they were more likely to report being in dependent living situations.

For the 33 States or jurisdictions that had a response rate of 75 percent or greater for the supplemental source of income support measure (accounting for 61 percent of admissions in 2009), 32.6 percent of abstinent admissions reported income from wages or salary, and 32.1 percent reported no income (Table 3). Among nonabstinent admissions, 25.9 percent reported income from wages or salary, and 38.0 percent reported no income. Thus, abstinent were more likely than nonabstinent admissions to report income from wages or salary and were less likely to report no income.

The majority of abstinent admissions had at least one prior admission to treatment, and 44.5 percent had no prior admissions (Table 4). Slightly less than one fifth (19.8 percent) of admissions that reported being abstinent had three or more prior admissions. In comparison, 42.4 percent of admissions that did not report abstinence had no prior admissions, and 25.1 percent had three or more prior admissions.

| Characteristic | Percentage Abstinent at Admission, Past 30 Days |

Percentage Not Abstinent at Admission, Past 30 Days |

|---|---|---|

| Prior Treatment Episodes | ||

| None | 44.5% | 42.4% |

| One | 22.9% | 20.9% |

| Two | 12.8% | 11.7% |

| Three or More | 19.8% | 25.1% |

| Type of Service at Admission | ||

| Ambulatory | 85.5% | 54.0% |

| Outpatient | 69.6% | 42.5% |

| Intensive Outpatient | 15.9% | 9.9% |

| Ambulatory Detoxification | 0.1% | 1.6% |

| Rehabilitation/Residential | 13.5% | 19.0% |

| Short-Term Residential | 4.2% | 11.2% |

| Long-Term Residential | 9.1% | 7.3% |

| Hospital (Non-Detoxification) | 0.1% | 0.4% |

| Detoxification (24-Hour Service) | 1.0% | 27.0% |

| Free-Standing Residential | 0.9% | 21.9% |

| Hospital Inpatient | 0.1% | 5.1% |

| NOTE: Percentages may not sum to 100 because of rounding. Individual percentages for types of service (e.g., "Outpatient," "Intensive Outpatient," and "Ambulatory Detoxification") also may not sum to the percentage for a broader service category (e.g., "Ambulatory") because of rounding. Source: SAMHSA Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS), 2009. |

More than 85 percent of abstinent admissions were admitted to ambulatory treatment, including 69.6 percent that were admitted to outpatient treatment and 15.9 percent that were admitted to intensive outpatient treatment (Table 4). In addition, 13.5 percent of abstinent admissions were admitted to residential treatment, including 4.2 percent that were admitted to short-term residential treatment (30 days or less) and 9.1 percent that were admitted to long-term residential treatment; long-term residential treatment could include transitional living arrangements such as halfway houses. Small percentages of abstinent admissions were admitted to ambulatory (i.e., outpatient) detoxification (0.1 percent), free-standing residential detoxification (0.9 percent), or hospital inpatient detoxification (0.1 percent).

In comparison, slightly more than half of nonabstinent admissions were admitted to outpatient (42.5 percent) or intensive outpatient treatment (9.9 percent). Nonabstinent admissions were almost 3 times as likely as abstinent admissions to be admitted to short-term residential treatment (30 days or less) (11.2 vs. 4.2 percent). For nonabstinent admissions, 21.9 percent were admitted to free-standing residential detoxification, and 5.1 percent were admitted to hospital inpatient detoxification.

Treatment Outcomes among Abstinent Admissions in 2008Discharges from outpatient, intensive outpatient, and long-term residential treatment in 2008 that reported abstinence at admission had a higher median LOS than did admissions that were not abstinent (Figure 4). In particular, the median LOS for discharges from intensive outpatient treatment was 67 days for abstinent admissions and 48 days for nonabstinent admissions. For discharges from long-term residential treatment, the median LOS was 73 days if abstinence at admission was reported and 51 days if use of a primary or secondary substance was reported.

|

| Treatment Modality | Median Length of Stay, in Days | |

|---|---|---|

| Abstinent at Admission, Past 30 Days |

Not Abstinent at Admission, Past 30 Days |

|

| Outpatient | 99 days | 86 days |

| Intensive Outpatient | 67 days | 48 days |

| Short-Term Residential | 28 days | 22 days |

| Long-Term Residential | 73 days | 51 days |

| Source: SAMHSA Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS), 2008. |

Discharges from outpatient, intensive outpatient, and long-term residential treatment that reported no substance use in the 30 days before they were admitted to treatment were more likely to complete treatment than their counterparts that reported use (Table 5). In particular, 49.1 percent of discharges from outpatient treatment that reported abstinence at admission completed treatment, compared with 37.8 percent of discharges from outpatient treatment that did not report abstinence at admission. Percentages completing short-term residential treatment were comparable for those that reported abstinence at admission (54.7 percent) and those that did not (54.9 percent). Among discharges from each level of care, those that reported abstinence at admission also were less likely to drop out of treatment than discharges that did not report abstinence.

| Modality/Reason for Discharge | Percentage Abstinent at Admission, Past 30 Days |

Percentage Not Abstinent at Admission, Past 30 Days |

|---|---|---|

| Outpatient Discharges | ||

| Completed Treatment or Transferred | 59.4% | 50.3% |

| Completed Treatment | 49.1% | 37.8% |

| Transferred | 10.3% | 12.6% |

| Dropped Out | 26.0% | 32.5% |

| Terminated | 6.0% | 7.4% |

| Other | 8.6% | 9.8% |

| Intensive Outpatient Discharges | ||

| Completed Treatment or Transferred | 63.9% | 54.4% |

| Completed Treatment | 42.4% | 32.2% |

| Transferred | 21.4% | 22.3% |

| Dropped Out | 19.0% | 26.7% |

| Terminated | 9.0% | 9.7% |

| Other | 8.0% | 9.1% |

| Short-Term Residential Discharges | ||

| Completed Treatment or Transferred | 78.0% | 72.2% |

| Completed Treatment | 54.7% | 54.9% |

| Transferred | 23.3% | 17.3% |

| Dropped Out | 11.2% | 17.5% |

| Terminated | 5.8% | 5.5% |

| Other | 5.1% | 4.8% |

| Long-Term Residential Discharges | ||

| Completed Treatment or Transferred | 66.1% | 59.5% |

| Completed Treatment | 49.8% | 43.7% |

| Transferred | 16.3% | 15.8% |

| Dropped Out | 20.1% | 28.0% |

| Terminated | 9.3% | 7.4% |

| Other | 4.5% | 5.0% |

| NOTE: Percentages for all mutually exclusive outcomes within a modality may not sum to 100 because of rounding. Percentages for "Completed Treatment" and "Transferred" within a modality also may not sum to the percentage for "Completed Treatment or Transferred" because of rounding. Source: SAMHSA Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS), 2008. |

About one in four admissions to substance abuse treatment in 2009 reported no use of primary or secondary substances in the 30 days prior to admission. Even though these admissions reported abstinence, supplemental DSM data suggest that the large majority of these admissions nevertheless needed treatment for substance abuse, mental health conditions.

As noted previously, referrals from the criminal justice system—which accounted for nearly 60 percent of the abstinent admissions in 2009—could have been truly abstinent if they began treatment in a criminal justice setting or if their behavior was closely monitored prior to their entry into treatment. The additional 9 percent of abstinent admissions that were referred from substance abuse care providers also could have been truly abstinent in the 30 days prior to admission.

Furthermore, some of these abstinent admissions may have been truthful about their nonuse of primary or secondary substances in the 30 days prior to admission because TEDS data may not have captured all substance use. Admissions that reported no use of their primary substance of abuse could have used other substances in the past 30 days that were not recorded as secondary substances of abuse. Consequently, at least some of these admissions may have been abstinent from the substances for which they were identified as needing treatment, even if they were not totally abstinent from all substances in the 30 days prior to admission.

Admissions and discharge data also suggest that admissions in TEDS that reported no use of primary or secondary substances in the 30 days prior to admission may present with less severe substance abuse problems at admission than admissions that reported use. For example, abstinent admissions were more likely than those that were not abstinent to be admitted to the least intensive levels of care, outpatient and intensive outpatient treatment. Abstinent admissions to transitional living programs included in the category of long-term residential treatment (accounting for about 9 percent of abstinent admissions) also could have been truly abstinent if these programs required a period of prior abstinence at entry. In contrast, as a potential indicator of more severe substance abuse problems among nonabstinent admissions, more than one fourth of these admissions required services in an inpatient setting to provide for safe withdrawal from substance use.

Although a minority of admissions that reported abstinence were employed and received income from wages at admission, the percentages for abstinent admissions were higher than the corresponding percentages for nonabstinent admissions. Abstinent admissions also were less likely than nonabstinent admissions to report at admission that they were homeless. These findings further suggest that the substance use problems of these abstinent admissions were less likely to have progressed to the point at which they had lost jobs or stable housing. The younger average age of abstinent admissions also is consistent with seeking treatment at a less advanced stage of addiction. A lower level of problem severity at admission would be consistent with some success at abstaining from substance use despite the ultimate need for treatment.

In addition, discharge data from 2008 showed a longer median LOS and a greater likelihood of completing treatment at most levels of care if abstinence was reported at admission. Some limited success in abstaining for extended periods before entry into treatment might be preparation that increases a person's likelihood of completing treatment.

However, findings suggest that some admissions reporting abstinence attempt to minimize the extent of their substance use. Although low percentages of admissions that reported abstinence were admitted to detoxification, persons who had been completely abstinent in the 30-day period prior to admission would not be expected to require any services for withdrawal from substance use.

For the supplemental item on living arrangements, more than one in four adult admissions that reported being abstinent also reported that they were living in a supervised setting such as a residential institution, halfway house, or group home. Monitoring of persons and their possessions in these dependent living situations could identify instances of substance use or possession of substances that these persons may attempt to deny at admission to a treatment program. Especially if total abstinence is the expectation for individuals living in halfway houses following discharge from treatment, the tendency may be for persons coming from these living situations to minimize their use or its extent at admission to a treatment program. Alternatively, close monitoring of persons in these situations prior to their entry into treatment could have promoted abstinence.

As noted previously, TEDS includes large numbers of admissions and linked admission and discharge data but does not include all admissions to substance abuse treatment in the United States. Therefore, findings in this report can improve readers' understanding of the characteristics of admissions in TEDS that do not report use of primary or secondary substances in the 30 days prior to admission. However, these findings may not generalize to all admissions to substance abuse treatment.

An additional limitation is that data on abstinence or nonabstinence are based on admissions' self-reported frequency of use of primary or secondary substances in the 30 days prior to entering treatment. Although a limited window of time exists for detecting most drugs in urine, results of urine tests or tests of other biological specimens could identify some false negative reports of abstinence.

In addition, analyses for this report focused on the dichotomous measures of no use of primary or secondary substances and any use of primary or secondary substances in the 30 days prior to admission. Substance use in this latter group could range from relatively infrequent use to daily use. As noted previously, use or nonuse in the 30 days prior to admission is based on reports of the frequency of use of primary, secondary, and tertiary substances in this period. Except for admissions that reported daily use of a substance in the 30 days prior to admission, the total number of days that admissions used any substance could not be determined for admissions that used multiple substances at least once (but less than daily) in this period. Examination of characteristics of admissions reporting no primary or secondary substance use in the 30 days prior to admission, those reporting some (but not daily) use, and those reporting any daily use could be a topic for future investigation.

As indicated previously, the supplemental DSM data help to document the need for services among admissions in TEDS, even if no use of primary or secondary substances was reported in the 30 days prior to admission. Thus, periods of extended abstinence from most or all important substances of abuse prior to entering treatment also would not necessarily negate a person's need for substance abuse treatment services. Additional increases in the response rates among States and jurisdictions for this supplemental item would be important to policymakers and data users for evaluating whether these DSM diagnosis data are characteristic of abstinent admissions in general.

| The CBHSQ Data Review is published periodically by the Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (formerly the Office of Applied Studies), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). All material appearing in this report is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied without permission from SAMHSA. Additional copies of this report or other reports from the Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality are available online: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/. Citation of the source is appreciated. For questions about this report, please e-mail: Deborah.Trunzo@samhsa.hhs.gov. |

|

|