Science Features

Guests arrive at the Elwha Dam for the ceremony commemorating the official start of the dam decommissioning and river restoration project on the Elwha River in Washington state.

Over the last decade, the strategic decommissioning of obsolete or unsafe dams has become more common, with dam removal benefiting aquatic and streamside – or riparian – ecosystems. When natural river flow and sediment delivery regimes are restored, the result is a revitalization of degraded river channels and floodplains. At the same time, migratory pathways of commercially valuable or threatened species, such as Pacific salmon or American eels, are reestablished. In these cases, the benefits and ecological effects of decommissioning span upstream and downstream of the dam site, as well as into surrounding watersheds.

The USGS, working with partners across the country, has been studying how the river’s shape and form and ecological outcomes of dam decommissioning. USGS’s multi-disciplinary science helps decision makers answer fundamental questions about the downstream effects of dams and whether restoration targets are being achieved with dam removal.

Elwha River Restoration: Rebirth of a River

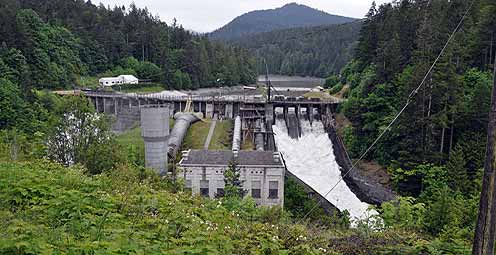

The USGS is an important science partner in the country’s largest dam decommissioning project, now under way in Olympic National Park in northwest Washington state. On September 17, 2011, the National Park Service began the simultaneous removal of the 108-foot tall Elwha Dam and the 210-foot tall Glines Canyon Dam on the Elwha River. For years previous to this day, the USGS worked with a number of partners, including the NPS, NOAA, the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, and others to conduct research and monitoring studies throughout the watershed. After establishing the baseline conditions for ecosystem components such as fish, wildlife, and riparian or streamside communities, scientists are continuing to monitor the rebirth of this river (for a slideshow showing marine sea life near the Elwha River’s mouth, click here.

Photo from a webcam showing the decommissioning of the Glines Canyon Dam, built in 1927 inside of Olympic National Park. Photo courtesy of the National Park Service.

The removal of the dams and restoration of habitat will reconnect salmon to their historical spawning grounds inside of Olympic National Park. For nearly 100 years, salmon were limited to the lowest 5 miles of the river below the dams, where their population numbers declined and their spawning habitat diminished as gravels were captured and stored in the upstream reservoirs.

Over time, nearly 24 million cubic yards of sediment accumulated in the two reservoirs, enough to fill a NFL football stadium eight times. Sediment transportation is a complicated process, with a variety of potential outcomes for river and marine habitats depending on the timing and pattern of sediment movement. In the short term, the massive amounts of sediments eroded during dam decommissioning will affect the clarity of the water and the downstream river bed. Some possible negative effects are loss of salmon habitat and some of their food supplies. In the long term, a natural sediment supply should increase habitat for salmon, shellfish, eel grass, and other forms of life in the river and the marine waters into which the river flows. The controlled release of this sediment is playing a major role in the dam-removal methods and schedule. For a fact sheet about the project, click here, and for a video of an Elwha River fish weir, click here.

Return of the American Eels: Dam Removal in Shenandoah National Park

Young American eels, such as the one pictured here, are beginning to recolonize streams in Shenandoah National Park after the removal of a dam more than 90 miles downstream.

The American eel, which lives in major rivers, streams, and some lakes all along the Atlantic coast from Greenland to northern South America, is under consideration by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for federal listing as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act. New research co-authored by USGS researcher Nathaniel (Than) Hitt and DOI partners reveals the benefits of dam removal for American eel conservation. The research shows that removal of a large dam increased American eel migrations into Shenandoah National Park streams more than 90 miles away. This research evaluated eel abundances in the headwater streams of Shenandoah National Park and compared sites before and after the removal of a large downstream dam in 2004 on the Rappahannock River. Results of the study show that the immigration of small eels was primarily responsible for the observed increases in eel numbers. Although the dam did not prevent eel passage, the results indicate that it lowered eel abundances and altered eel populations within distant headwater streams. The benefits of dam removal may therefore extend far into headwater areas.

American eel numbers increased in Shenandoah National Park following the removal of a dam more than 90 miles downstream. Photo courtesy of Gary Tyson, Tiadaghton Audubon Society

Manatees are often used as sentinels for emerging threats to the ocean environment and human health. Read more

The USGS plans to "app-lify" data with a contest through Challenge.gov. Prizes will be awarded to the best overall app, the best student app, and the people’s choice. Read more

The world’s oldest known wild bird – now 62 – is a mother again. Read more

The recent past sheds light on preserving the future of economically and ecologically important native trout populations across the West. Read more

Washington, D.C., is a unique city full of landmarks and buildings that are recognizable worldwide. But how were these stone giants built? Read more

Hurricane Sandy is a stark reminder of just how essential it is for the Nation to become more resilient to coastal hazards.Read more

The 100 million tons of carbon sequestered in western ecosystems each year is an amount equivalent to – and counterbalances the emissions of – more than 83 million U.S. passenger cars a year. Read more

Watch USGS scientists in the Arctic track Pacific walruses to examine how these animals are faring in a world with less sea ice. Read more

Critically endangered birds whose numbers grew rapidly after successful translocations by USGS and USFWS biologists likely took a hit from the 2011 event. Read more

Trees Face Rising Drought Stress and Mortality as Climate Warms. Read more

Saltmarshes may slow the rate of climate change. Read more

USGS vigilant for West Nile virus in wildlife through surveillance, research, and mapping.

USGS and its partners are investigating the unusual deaths of New England harbor seals. Read more

USGS scientists look to see if water quality is improving. Read more

The majority of the nation is facing dry conditions; in most areas drought conditions are expected to persist or intensify. Read more

Maximizing alternative energy’s potential – how science can help grow the nation’s energy portfolio. Read more

Please comment on the USGS’ draft science strategies! Read more

USGS Details how climate change could affect water availability in 14 U.S. Basins. Read more

Western stream temperatures are not warming at the same rate as air temperature.Read more

Long polar bear swims provide tantalizing clues.Read more

The larger and more aggressive Eastern species thrives in a threatened species’ forest habitat.

While on your spring hike, beware of hitchhiking ticks—they may carry Lyme Disease.

For the first time since its discovery, White-nose syndrome has been found in the West.

The family picnic: food and fun...until unwanted guests show up! Learn what you can do to prevent West Nile virus from infecting your loved ones.

Timing is everything! Consider helping track changes in spring’s arrival

Flood Safety Awareness Week is March. 12-16. What can you do to prepare?

National Groundwater Awareness Week is Mar. 11-17, 2012. See how USGS science is connecting groundwater and surface water.

Since Japan’s March 11, 2011, Tohoku earthquake and subsequent tsunami, scientists at the USGS have learned much to help better prepare for a large earthquake in the United States.

Five USGS employees honored with Distinguished Service Awards for their service to the nation

It’s National Invasive Species Awareness Week. Did you know invasive species cost our country more than 100 billion dollars each year? Get to know America’s ten top invaders this week.

It’s National Invasive Species Awareness Week. Did you know invasive species cost our country more than 100 billion dollars each year? Get to know America’s ten top invaders this week.

It’s National Invasive Species Awareness Week. Did you know invasive species cost our country more than 100 billion dollars each year? Get to know America’s ten top invaders this week.

It’s National Invasive Species Awareness Week. Did you know invasive species cost our country more than 100 billion dollars each year? Get to know America’s ten top invaders this week.

The proposed USGS budget reflects research priorities to respond to nationally relevant issues, including water quantity and quality, ecosystem restoration, hydraulic fracturing, natural disasters such as floods and earthquakes, and support for the National Ocean Policy, and has a large R&D component.

Mid-sized mammals in Everglades National Park are getting a big squeeze from invasive Burmese pythons, according to a USGS co-authored study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

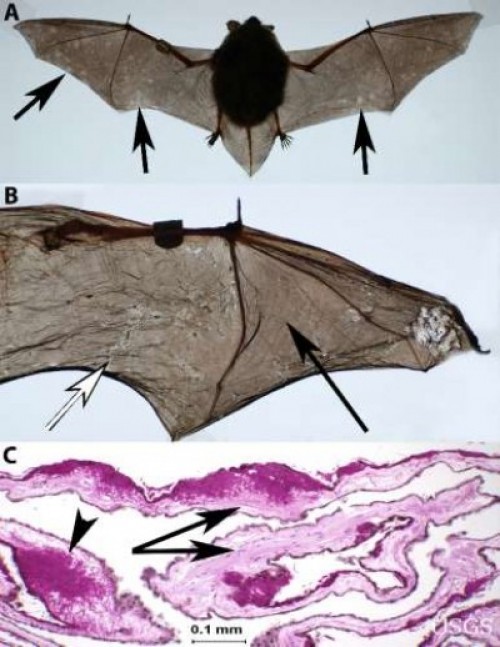

Bat populations, which provide valuable insect control, are declining at an alarming rate due to white-nose syndrome. Scientists have definitively identified the cause of this deadly syndrome.

Two adolescent cranes, raised by humans and reintroduced into the wild, were shot and killed. Sadly, they are not the first. How many killed this year? How many are left?

By 1936, devastating losses of wildlife populations were threatening the Nation’s natural resource heritage. America's first wildlife research center

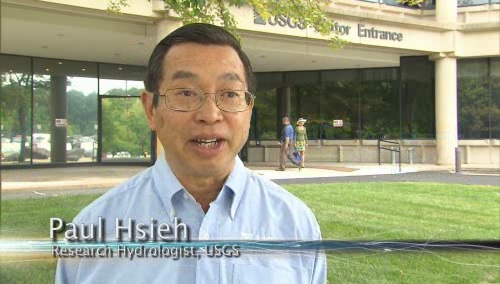

As the team of responders struggled to end the worst oil spill in our Nation’s history, USGS scientist Paul Hsieh provided the critical scientific information needed to make a crucial decision.

The movie Contagion dramatizes the scenario of a global pandemic that begins with the spread of a disease from animals to humans. What are real-life experts doing to prevent a pandemic that originates with wildlife?

After years of planning, the Department of the Interior has begun removing two dams on the Elwha River in Washington. But how will the removal of these dams impact the river’s sediments, waters, and fish?

As a nation, we use more than 75 billion gallons of groundwater each day. September 13 is the National Groundwater Association’s “Protect Your Groundwater Day.” What we can do to ensure we continue to have enough of it?

Secretive and rare stream-dwelling amphibians are difficult to find and study. Scientists at the US Geological Survey and University of Idaho have developed a way to detect free-floating DNA from amphibians in fast-moving stream water.

Within the rivers, streams, and lakes of North America live over 200 species of freshwater mussels that share an amazing life history. Join us in Reston, VA to explore the fascinating reproductive biology and ecological role of one of nature’s most sophisticated fishermen.

USGS scientists are working to characterize the contaminants and habitats for a number of aquatic species along the lower Columbia River.

Forests play a significant role in removing carbon from the atmosphere by absorbing one-third of carbon emissions annually. This is according to a new U.S. Forest Service study conducted in collaboration with USGS scientists.

New USGS research shows that rice could become adapted to climate change and some catastrophic events by colonizing its seeds or plants with the spores of tiny naturally occurring fungi. The DNA of the rice plant itself is not changed; instead, researchers are re-creating what normally happens in nature.

A new study supports the ecological reliance of red knots on horseshoe crabs. The well-being of red knots, a declining shorebird species, is directly tied to the abundance of nutrient-rich eggs spawned by horseshoe crabs.

USGS crews continue to measure streamflow and collect water quality and sediment samples in the Ohio and Mississippi River basins using state-of-art instruments.

Native Bees are Selective About Where They Live and Eat -- It's National Pollinator Week, and here's groundbreaking research about the world of our native bees.

As hurricane season starts, researchers are modeling potential changes to coastal environments to identify communities vulnerable to extreme erosion during storms. Data collected before and after storm landfall are used to verify past forecasts and improve future predictions.

Follow the Pacific Nearshore Project as researchers from the USGS, Monterey Bay Aquarium, and other institutions sail Alaskan waters to study sea otters and investigate coastal health.

USGS science supports management, conservation, and restoration of imperiled, at-risk, and endangered species.

New USGS research shows that certain lichens can break down the infectious proteins responsible for chronic wasting disease, a troubling neurological disease fatal to wild deer and elk and spreading throughout the United States and Canada.

It's time to celebrate the essential role wetlands play in giving us food and water; sheltering us from storms, floods, and coastal erosion; providing habitat for birds, fish, and other wildlife; and cleaning and storing water.

In a unique application of data, this year's report provides the nation's first assessment of birds on public lands and waters.

For reliable information about amphibians and the environmental factors that are important to their management and conservation, visit the new USGS Amphibian Monitoring and Research Initiative website.

A new article explains the economic importance of insect-eating bats to U.S. agriculture and how white-nose syndrome and wind turbines threaten these valuable animals.

Using coral growth records and measurements of changing ocean chemistry from increased atmospheric CO2, USGS scientists are providing a foundation for predicting future impacts of ocean acidification and sea-level rise to coral reefs.

Non-native lionfish are rapidly spreading along the U.S. Eastern seaboard, Gulf of Mexico, and Caribbean and have been preying on and competing with a wide range of native species.

On Midway Island, Wisdom, a 60-year-old albatross, and her chick made it through the tsunami that resulted from the magnitude 9.0 earthquake off of Japan on March 11.

Please answer questions about USGS Ecosystems science.

Join us in learning about wildlife conservation research with Dr. Matthew Perry as we celebrate the 75th anniversary of the USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center. Major programs include global climate change studies, Chesapeake Bay studies, and wildlife conservation monitoring.

Glen Canyon Dam High-Flow Experiments Provide Insights for Colorado River Management.

Demand for alternative energy sources leads scientists to consider microbes as potential sources of power.

Human health, ecological health, and environmental health are closely connected. Join us to learn how USGS science contributes to our understanding of how such environmental factors affect health threats.

A new identification guide provides images and geographic distributions of diatoms, an important group of algae.

A new USGS video highlights five decades of photographic documented change in coral reef conditions in the Florida Keys.

The USGS National Wildlife Heath Center is working with state agencies in investigating the death of thousands of birds in Arkansas and Louisiana.

Combining traditional ecological knowledge with empirical studies allows the the USGS, Tribal governments, and native organizations to increase their mutual understanding of the current health of Tribal lands and waters.

Scientists have found that the fungus associated with white-nose syndrome in bats is unlike that of any known fungal skin pathogen in land mammals. It is extremely destructive to bats wing skin and may cause catastrophic imbalance in life-support processes.

Sea-ice habitats essential to polar bears would likely respond positively should more curbs be placed on global greenhouse gas emissions, according to a new modeling study published today in the journal, Nature.

Remotely triggered thermal-imagery cameras will be used in a new non-invasive way to study mange in wolves.

Landscape photos taken in the same place but many years apart reveal dramatic changes due to human and natural factors. The USGS Desert Laboratory Repeat Photography Collection, the largest archive of its kind in the world, is 50 years old.

Decreasing pH and warming temperatures are changing ocean conditions and affecting coral and algal growth in South Florida. USGS scientists are conducting field measurements to learn more.

Many coastal wetlands worldwide including several on the U.S. Atlantic coast may be more sensitive than previously thought to climate change and sea-level rise in the this century.

Efforts are underway to restore the Greater Everglades Ecosystem, which has been profoundly altered by development and water management practices. Join us on December 1st when Dr. Lynn Wingard shares USGS research that is helping restoration management agencies develop realistic and attainable restoration goals for the region.

Eight specially trained whooping crane chicks hatched in May have now embarked on their first southward migration, with an ultralight airplane leading them. USGS researchers who hatched, raised, and trained the chicks at the USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, are eagerly following the cranes on their journey.

Beak abnormalities, which make it difficult for birds to feed and clean themselves, are occurring in large numbers of Black-capped Chickadees, Northwestern Crows, and other species in the Pacific Northwest and may signal a growing environmental health problem.

The USGS strongly supports the national celebration of Geography Awareness Week, November 14-20, and this year’s theme: Freshwater. The “where” factor of geography integrates USGS studies in many fields of science.

Two new tools that enable the public to report sick or dead wild animals could also lead to the detection and containment of wildlife disease outbreaks that may pose a health risk to people.

USGS scientists are investigating sea turtles and their habitats in Dry Tortugas National Park to provide insight that will be used as decision-support tools for managing coral ecosystems.

Looking for information on natural resources, natural hazards, geospatial data, and more? The USGS Education site provides great resources, including lessons, data, maps, and more, to support teaching, learning, K-12 education, and university-level inquiry and research.

The Chesapeake Bay has long been an R&R destination for DC residents. However, the watershed’s overpopulation contributes to its decline. Join us when USGS’s Scott Phillips and Peter Claggett discuss new science efforts applied to restoring the Nation's largest estuary on October 6th.

Nutrient sources in both agricultural and urban areas contribute to elevated nutrient concentrations in streams and groundwater across the Nation.

The timing of animal migration and reproduction, and observing when plants send out new leaves and bear fruit, is increasingly important in understanding how climate change affects biological and hydrologic systems. Photo credit Copyright C Brandon Cole.

The USGS has been researching manatees in Florida and the Caribbean for decades, but little is known about Cuban manatees. A USGS biologist recently visited Cuba with a team of international manatee experts working to conserve manatees around the Caribbean.

USGS scientists have discovered a new turtle species, the Pearl River map turtle, found only in the Pearl River in Louisiana and Mississippi. Sea-level changes between glacial and interglacial periods over 10,000 years ago isolated the map turtles, causing them to evolve into unique species.

USGS scientists help land managers determine if fire is the appropriate strategy for controlling or enhancing specific plant species.

Did you know that contaminant-ridden dust from Africa may be harming coral reefs in the Caribbean? Scientists at the USGS are examining the air in Africa and in the Caribbean to determine what kinds of nutrients, microbes, and contaminants are traveling across the ocean.

Pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities can be a significant source of pharmaceuticals in surface water. The USGS is working with water utilities to try to reduce the release of pharmaceuticals and other emerging contaminants to the environment.

The USGS Science Strategy is a comprehensive report to critically examine the USGS's major science goals and priorities for the coming decade. The USGS is moving forward with these strategic science directions in response to the challenges that our Nation's future faces and for the stewards of our Federal lands.

Join us in Reston on December 5th at 7:00pm for our free public lecture on the impacts of offshore wind energy development on migratory seabirds!

USGS wishes The Wildlife Society happy 75th Birthday and looks forward to attending their annual conference. Stop by our booth!

7 p.m.—Public lecture (also live-streamed over the Internet)

Join us for the July Public Lecture on Invasive Species!

USGS-led survey finds that national wildlife refuges rate highly with visitors.

As the climate has warmed, many plants are starting to grow leaves and bloom flowers earlier. A new study published in the journal, Nature, suggests that most field experiments may underestimate the degree to which the timing of leafing and flowering changes with global warming.

Stressed agricultural lands may be releasing less of the moisture needed to protect the breadbasket of a continent.

Spring rains in the eastern Horn of Africa are projected to begin late this year and be substantially lower than normal.

After nearly 2 years of meticulous research, academic and government scientists confirmed that the 2010 oil spill had damaged local coral ecosystems

In recognition of World Forestry Day, let’s take a glimpse at USGS science to understand the fate of forests from climate change.

Join us on March 7 to learn about bat white-nose syndrome, which has killed an estimate 5 million bats, and to discuss the profound impacts this emergent wildlife disease may have in the 21st century.

The U.S. Geological Survey had a very busy 2011 — below are a few of our highlights from last year.

Scientists have discovered an outbreak of coral disease called Montipora White Syndrome in Kāneohe Bay, Oahu. The affected coral are of the species Montipora capitata, also known as rice coral.

Perhaps some of you have already experienced a sweet holiday smooch or two under the Christmas mistletoe, enjoying this fairly old kissing ritual for people. But mistletoe is important in other vital ways: it provides essential food, cover, and nesting sites for an amazing number of critters in the United States and elsewhere.

USGS scientists will join thousands of scientists, managers, and decision makers in Boston this week to present new findings on toxics at the Society for Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC) conference in the Hynes Convention Center, Nov. 13-17.

On Nov. 3, USGS scientists Patrick Barnard and William Ellsworth will present a public lecture in Menlo Park, CA, providing Bay Area residents information about USGS research in the San Francisco Bay Area, including recent discoveries beneath San Francisco Bay and ongoing studies to better understand earthquake probabilities and the potential hazards associated with strong ground shaking.

Meet the R/V Muskie and the R/V Kaho, the USGS Great Lakes Science Center's two newest additions to its Great Lakes research fleet!

As climate changes, it affects the timing of when leaves emerge, the amount of foliage that grows as well as the timeframe when leaves begin to fall.

How will accelerated glacial melting over the next 50 years as a result of climate change affect the unique Gulf of Alaska and Copper River coastal ecosystems? USGS scientists are studying these processes and impacts.

The U.S. Geological Survey research looked at one of the world’s largest populations of long-tail ducks and found that hundreds of thousands of these elusive birds engage in a bizarre 30-50 mile morning commute from Nantucket Sound to the Atlantic Ocean, returning each evening.

Taking advantage of USGS expertise in satellite telemetry, geospatial mapping and analysis and waterfowl migration monitoring, researchers have tracked waterfowl across Asia, Eastern Europe, and Africa and discovered new flu transmission links.

USGS is working in collaboration with numerous state and federal agencies and tribes to obtain approval for field trials with vaccine-laden, peanut-butter flavored baits and evaluate the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine in grasslands.

Psychedelically colored wolves depicted by thermal imaging will shed light on how mange affects the survival, reproduction and social behavior of wolves in Yellowstone National Park.

Accessibility FOIA Privacy Policies and Notices

![]() U.S. Department of the Interior |

U.S. Geological Survey

U.S. Department of the Interior |

U.S. Geological Survey

URL: www.usgs.gov/blogs/features/usgs_top_story/freed-rivers-foster-return-of-stream-migrations/

Page Contact Information: Ask USGS

Page Last Modified: September 14, 2011

Loading Page...

Loading Page...