![]()

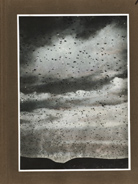

![]() Locust. Image from Locust Plague of 1915 photograph album (page 34). American Colony in Jerusalem Collection, Manuscript Division, LOC

Locust. Image from Locust Plague of 1915 photograph album (page 34). American Colony in Jerusalem Collection, Manuscript Division, LOC

Witnesses to the locust invasion that befell Jerusalem and the nearby Syrian region in 1915 agreed that they had seen nothing to equal it in their life-times. It was truly a natural disaster of biblical proportions.

Members and employees of the American Colony were active in complying with official eradication efforts during the plague. They cooperated with provincial Ottoman authorities who marshaled organized resistance to the locusts at the command of Djemal (Jamal) Pasha, head of the Fourth Army on the Palestine Front and military governor of Ottoman Syria, and volunteered their labor to help fight off the gregarious pests and limit their numbers and advances.

The American Colony also played an important historic role in documenting the 1915 invasion as a major social and economic event, as well as one of scientific interest. At the behest of Djemal (Jamal) Pasha, Lewis Larsson, the head of the American Colony Photo Department, worked with the assistance of Lars Lind and John D. Whiting to record the 1915 destruction. Larsson photographed the various methods that American Colony members and other Jerusalemites used to try to control the onslaught. He undertook a series of carefully staged studio “insect portraits” in which American Colony photographers captured details of the physical nature of individual locusts and their various stages of molting. And he supervised the compilation of selected images of the plague into photographic albums created by the American Colony photo service. These albums contained hand-tinted photographic prints that graphically captured the story of the invasion, conveyed in dramatic fashion.

![]() View the complete photograph album

View the complete photograph album

Documenting the Invasion

Copies of the photograph albums documenting the locust plague of 1915 that were created by the American Colony Photo Department were retained by American Colony members as visual reminders of the incredible phenomenon they had all experienced. The albums, each uniquely and aesthetically hand-tinted, were also made available for commercial sale through American Colony venues. The American Colony images attracted international attention.

Individual prints documenting the plague created by Lewis Larsson for the American Colony Photo Department were among the twenty-five photographic illustrations featured in an article entitled “Jerusalem’s Locust Plague” that John D. Whiting published in the December 1915 (volume 28) issue of The National Geographic Magazine. The images used in the article either matched or were similar to those appearing in the albums. In the article, Whiting described the natural history of the locusts and the particular course and consequences of their destruction. He included anecdotes about his own family and friends of the American Colony, and reported local reactions to the invasion. He described the mechanics of eradication efforts. He also addressed larger philosophical issues, including the moral lessons drawn by witnesses regarding divine power and notions of fate and destiny. He made allusions to the similarities between the 1915 plague and descriptions of locusts in the ancient sayings of Mohammed and in books of the Bible, including the books of Joel and Exodus. And he addressed the economic impact and the very real needs that Jerusalemites faced in the aftermath of the locusts’ visit.

The Locust Plague: Online and Physical Resources

The photograph album of the 1915 locust plague preserved in physical format in Part I of the American Colony in Jerusalem collection in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress has been digitized in full (fifty-seven images) and is available electronically through this Web site.

A second example of a hand-tinted locust album created by the American Colony is preserved in physical format within the Manuscript Division’s John D. Whiting Papers collection. The Whiting collection also includes an original printed copy of the locust article Whiting published in National Geographic.

Individual digitized images of locust plague abatement in Palestine that were created from 1915 glass-plate negatives in the G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection in the Prints and Photographs Division (as well as other images documenting later infestations of the 1930s), are available online through the Prints and Photographs Online catalog. There are black-and-white glass-negative images in the Matson photographic collection that closely match the hand-tinted prints which appear in the albums.

Also on the Library of Congress Web site, see the Locust Plague section of The American Colony in Jerusalem virtual exhibition, which highlights the role of the administration of Djemal (Jamal) Pasha, and the Manuscript Division's Acquisition Highlight on the John D. Whiting Papers collection.

The Course of the Plague

Swarms of locusts were not unprecedented in the desert environment and periodic visitations to vegetated areas could be expected. Indeed, the year 1865 was still colloquially known as the “year of the locusts.” Barley and wheat fields in the Jordan Valley near Jericho had been eaten down to stubs in 1892, and there were subsequent localized events in 1899 and 1904. But the locust invasion of 1915, which began in Palestine in February, took hold in March and April, and lasted through June—and in some areas of the region, into October—astonished the locals in its length and ferocity.

![]()

![]() Swarming locusts. Image from Locust Plague of 1915 photograph album (page 1). American Colony in Jerusalem Collection, Manuscript Division, LOC

Swarming locusts. Image from Locust Plague of 1915 photograph album (page 1). American Colony in Jerusalem Collection, Manuscript Division, LOC

As the American Colony locust albums and Whiting’s article document, the locusts moved across the Palestinian landscape upon the hundred thousands, forming various waves during their different stages of existence. As the first image in the album depicts, they made their initial appearance as great clouds of flying insects, darkening the day-time skies as they approached Jerusalem from the northern horizon.

Flocks of storks and other birds were among the natural predators that pursued and consumed the flying swarms, but not to a degree to effectively decrease their numbers. Larsson first observed swarms darkening the sun while he was traveling on the border of the wilderness of Judea in February 1915, and by March 1915 he, Whiting, and Lind were volunteering in the eradication effort.

In the next phase of the plague, female flying locusts laid eggs in the ground, giving rise to the second, and most devastating, stage of the invasion. On April 19, 1915 local authorities issued a proclamation obligating men from age sixteen to sixty to gather and turn in several pounds of eggs each, or pay a fine, all in an effort to limit the multitude of eggs soon to hatch. Tens of thousands of new locusts could potentially be produced from eggs laid in just a few meters square of earth. The young men of the American Colony dutifully set about meeting the requirement.

Soon the newly hatched larva emerged, wingless, and began moving in droves so vast viewing them made some witnesses motion sick. These crawlers advanced over the face of the earth, consuming everything edible in their path. They blanketed the road near the Jerusalem railroad station. They mobilized in countless rows like armies, leaving large portions of previously thriving landscapes devoid of vegetation. Former shade trees were rendered leafless. The locusts burrowed inside the trunks of palms and cactus. They invaded bee hives, consuming honey and bees alike. As images on pages six and seven of the album convey (in striking “before” and “after” shots), even the flowers and bushes of the carefully tended Garden of Gethsemane were obliterated.

![]()

![]() Gethsemane before and

Gethsemane before and ![]() after the arrival of the desert locusts. Images from Locust Plague of 1915 photograph album (pages 6 & 7). American Colony in Jerusalem Collection, Manuscript Division, LOC

after the arrival of the desert locusts. Images from Locust Plague of 1915 photograph album (pages 6 & 7). American Colony in Jerusalem Collection, Manuscript Division, LOC

The locusts devastated long-standing orchards and laid vineyards to waste, leaving twisted remnants of vine branches behind on the barren earth. They climbed up fig trees, covering the trunks and extending to the ends of twigs and branches. The leaves of a large flourishing fig tree could be completely stripped in a matter of minutes (as “before” and “after” images illustrate). The locusts destroyed carefully tended vegetable gardens, leaving some young fruit and stripping other fruit down to the pits. They gnawed the tender bark of branches into nubs, leaving them to look, as Whiting observed in his article, like white candles extending from the ends where foliage once sprouted. Olive, pomegranate, apricot, quince, fig and cypress were all marked for destruction. The locusts crawled like relentless miniature battalions up the sides of the Tower of David, over the garden walls of the American Colony, and through the windows and roofs of Jerusalemites’ homes.

![]()

![]() A tree before and

A tree before and ![]() after the arrival of the desert locusts. Images from Locust Plague of 1915 photograph album (pages 12 & 13). American Colony in Jerusalem Collection, Manuscript Division, LOC

after the arrival of the desert locusts. Images from Locust Plague of 1915 photograph album (pages 12 & 13). American Colony in Jerusalem Collection, Manuscript Division, LOC

The sheer numbers and relentless nature of the locusts was hard to comprehend. Whiting relates that in Nazareth, droves were crunched beneath the feet of pedestrians who needed to move through the narrow streets, as well as under the wheels of wagons. A stench rose up from the slimy mass that was so malodorous it made occupation of the town almost unbearable. Residents of Jerusalem strived, mostly in vain, to divert the pests with brooms, charms, and prayers. Some gave in to fatalism. As the insects spread, people exchanged various folkway remedies. Those who chose to combat the locusts, including the American Colony members, learned from experience how best to adapt their methods to better and more efficient outcomes.

Eradication Efforts

![]()

![]() Eradication efforts: herding locusts into a trap. Image from Locust Plague of 1915 photograph album (page 18). American Colony in Jerusalem Collection, Manuscript Division, LOC

Eradication efforts: herding locusts into a trap. Image from Locust Plague of 1915 photograph album (page 18). American Colony in Jerusalem Collection, Manuscript Division, LOC

In his December 1915 National Geographic article, American Colony leader John D. Whiting describes the technology the American Colony members and their neighbors used, whereby they placed sunken boxes made of wood boards, sided with tin, into the earth. These functioned as pit traps. A group of people would then wave dark-colored flags to herd the insects. The crawling locusts would move away from the shadows cast as individuals waved the flags, whereupon they were forced into a tightly concentrated streaming mass, and urged forward. As they approached the brink of the sunken traps, they would drop inside in steady streams, the smooth sides of the box preventing their exit. Innovation proved that a tilted ramp that ran up into a tin-lined box placed above the ground worked as well as the sunken method, and was easier to empty and re-use. Still more innovation produced a ramped framework to which bags could be attached for the locusts to drop into, replacing the box trap and making it easier to dispose of the captured locusts. These techniques are illustrated in images on pages 18 through 22 in the 1915 album.

After capture and transfer into large sacks, some locusts were burned. (The flame-thrower would become a welcome tool for combating locusts in the next great invasion, in 1930, in which the American colonists also participated). But in the times of scarcity, the bagged locusts were utilized. They were first dipped into boiling water and then spread out in the sun to dry. Roasted and dried locusts had long been a source of protein in the diets of desert-dwellers. The American Colony members used the locusts they gathered through the eradication process as feed for the colony’s pigs and chickens and other farm stock. The feed affected the color of chicken eggs, tinging omelets served at American Colony tables pink, much to the wonder of the children.

Scientific Illustration

![]()

![]() Studio study of a molting locust. Image from Locust Plague of 1915 photograph album (page 42). American Colony in Jerusalem Collection, Manuscript Division, LOC

Studio study of a molting locust. Image from Locust Plague of 1915 photograph album (page 42). American Colony in Jerusalem Collection, Manuscript Division, LOC

There were several stages in the lives of the invading locusts, which were of the familia Acrididae and genus Schistocerca, subspecies gregaria, also known as Schistocerca peregrina, or vernacularly in English as the desert locust. In the generation that followed the initial fliers, eggs produced larvae and the voracious wingless crawling locust. Then came the molting process, in which the nymph skin was shed and metamorphosis took place to produce hoppers whose pliable outer bodies needed to harden into their mature state, and wings emerge and dry. All these phases were carefully documented in specimen studio photographs made by the American Colony Photo Department. These images are included in the latter portion of the digitized locust album. Newly generated locusts favored rock walls and trees as warm places to alight before they rose and disappeared in masses in further migratory flight.

Economic Consequences

At the base of all eradication efforts was fear of famine and immediate and long-term food shortages. The damage caused by the invasive locusts of 1915 left the formerly plentiful fruit and vegetable stalls of the Jerusalem marketplace empty of local produce. In the countryside, the scourge created alarming scarcity in the staples of local diets, especially olive oil. Fresh food commodity prices were driven up in a time when residents of the region were already experiencing shortages, complicated by the economic realities of the war (the British had declared war on Turkey the previous fall, and Turkish rule in the Near East would end in 1918). With vineyards and summer vegetable crops destroyed, wine and produce were available only to the rich and those with access to foreign imports. Peasants in rural areas were denied both their livelihoods and means of providing important sources of nutrition to their families.

![]()

![]() Djemal (Jamal) Pasha on the shore of the Dead Sea, May 1915. Image from World War I in Palestine and the Sinai photograph album (page 1). American Colony in Jerusalem Collection, Manuscript Division, LOC

Djemal (Jamal) Pasha on the shore of the Dead Sea, May 1915. Image from World War I in Palestine and the Sinai photograph album (page 1). American Colony in Jerusalem Collection, Manuscript Division, LOC

The American Colony Photo Department locust photograph albums and John D. Whiting’s National Geographic article were prepared primarily as historic documentation. The studio studies of the locusts in metamorphosis functioned as pseudo-scientific natural history records. But the images as a whole were reminders to the world of what can happen in such a natural disaster. The commercially distributed albums served as reference records for those in the future who would face similar infestations. They also had a more immediate purpose. They were means to educate an interested western audience and alert them to the need for charitable food assistance to the region.