Transitional Living Programs Move Homeless Youth Closer to Independence

This issue of The Exchange takes an insider’s look into what makes for successful transitional living programs and includes tips on starting, managing, funding, and evaluating a program that helps young people become independent, self-sufficient adults.

Programs around the country are easing the transition to adulthood for runaway and homeless youth. Through the Family and Youth Services Bureau’s Transitional Living Program for Older Homeless Youth, more than 5,000 runaway and homeless youth a year receive housing, life skills training, counseling, and education and employment support from local organizations. This issue of The Exchange takes an insider’s look into what makes for successful transitional living programs and includes tips on starting, managing, funding, and evaluating a program that helps young people become independent, self-sufficient adults.

Moving Homeless Youth Closer to Independence

Like thousands of young people in the United States each year, Catherine* couldn't go home. Last year, at age 16, she learned she was pregnant, and her parents asked her to leave. She and her boyfriend, Dillon, wanted to move in together, but they didn't have the money to support themselves-or adequate knowledge of the adult world of bank accounts, parenthood, and personal responsibility. They didn't just need a place to stay the night: "We needed to learn how to cook, clean, and budget," Catherine says.

Like thousands of young people in the United States each year, Catherine* couldn't go home. Last year, at age 16, she learned she was pregnant, and her parents asked her to leave. She and her boyfriend, Dillon, wanted to move in together, but they didn't have the money to support themselves-or adequate knowledge of the adult world of bank accounts, parenthood, and personal responsibility. They didn't just need a place to stay the night: "We needed to learn how to cook, clean, and budget," Catherine says.

The Family and Youth Services Bureau (FYSB) recognizes that many homeless and runaway youth are the victims of neglect, abandonment, or severe family conflict. They can't return to their families, but they are not yet equipped to live on their own. They have to work to support themselves, often without having even a high school degree. If they want to go to college, they have no one to help them pay for it or to fill out financial aid forms for them. They have to learn to cook for themselves instead of eating at home or in the university cafeteria. They have to seek their own role models, rather than leaning on their parents.

Without someone to guide them on their path to self-sufficient adulthood, homeless youth risk becoming involved in dangerous lifestyles. Many use drugs or alcohol, or participate in survival sex and prostitution to stay fed and alive.

Protecting young people from such fates and helping them thrive are the goals of FYSB's Transitional Living Program for Older Homeless Youth. Every year, more than 5,000 runaway and homeless youth receive housing, life skills training, counseling, and education and employment support from organizations such as Mendocino County Youth Program, in Ukiah, California, which runs the transitional living program Catherine and Dillon entered.

Congress created the Transitional Living Program for Older Homeless Youth as part of the 1988 Amendments to the Runaway and Homeless Youth Act. By 1990, the Family and Youth Services Bureau (FYSB) had funded the first Transitional Living Program projects. For the past 15 years, FYSBfunded transitional living programs have provided up to 18 months of residential services to homeless youth ages 16 to 21. (An additional 180 days is allowed for youth younger than 18.) Youth workers often use the terms "transitional living program" and "independent living program" interchangeably. Within the Federal government, however, they refer to two different grant programs: FYSB's Transitional Living Program (TLP) and the Children's Bureau's John H. Chafee Foster Care Independence Program (commonly referred to as ILP), a State-grant program that prepares current and former foster youth to live independently. A single agency may house both programs, and their fundamental services may be the same, but there may be some variation to accommodate the different needs of foster and homeless youth.

Transitional living programs, according to the people who run them, are about helping young people become independent. "TLP is a place where youth are trying to figure out what they want to do in life, and we help them to navigate that," says Michael Hinckley- Gordon, director of independent living programs at Good Will- Hinckley Homes for Boys and Girls in Hinckley, Maine.

While youth get lots of support from program staff in their quest for independence, they must have the will and determination to succeed. Theresa Nolan, director of runaway and homeless youth services at Green Chimneys Children's Services in New York City, likens her work to boxing training. "I tell youth they're the boxer, the TLP team is the manager and coach. We can give them training and support and cheer them on-but out in the ring, they're on their own."

While youth get lots of support from program staff in their quest for independence, they must have the will and determination to succeed. Theresa Nolan, director of runaway and homeless youth services at Green Chimneys Children's Services in New York City, likens her work to boxing training. "I tell youth they're the boxer, the TLP team is the manager and coach. We can give them training and support and cheer them on-but out in the ring, they're on their own."

Transitional living programs encourage self-sufficiency by using the Positive Youth Development approach, giving young people opportunities to exercise leadership, build skills, and get involved in their communities. Youth work with staff to create their own case plans, determining what they need to work on-whether it is learning to change a vacuum cleaner bag, exploring the world of work, or becoming a better listener. In scattered-site programs, in which youth live in their own apartments in the community rather than in a group home or agency-owned apartment building, youth find their own apartments and often sign their own leases, with support from program staff. And many programs let youth have some say in admitting new clients, adding or changing material in life skills curriculums, creating rules and rewards systems, and helping with other aspects of program design.

Transitional living programs encourage self-sufficiency by using the Positive Youth Development approach, giving young people opportunities to exercise leadership, build skills, and get involved in their communities. Youth work with staff to create their own case plans, determining what they need to work on-whether it is learning to change a vacuum cleaner bag, exploring the world of work, or becoming a better listener. In scattered-site programs, in which youth live in their own apartments in the community rather than in a group home or agency-owned apartment building, youth find their own apartments and often sign their own leases, with support from program staff. And many programs let youth have some say in admitting new clients, adding or changing material in life skills curriculums, creating rules and rewards systems, and helping with other aspects of program design.

Transforming formerly homeless youth into independent adults is not easy, program managers say, especially when most young people their age are not expected to shoulder so much responsibility. Add to that the fact that many clients come from difficult family backgrounds and have limited skills. "We're reparenting a lot of kids who haven't been parented for many years," says Jamie Van Leeuwen, director of development and public affairs of Urban Peak in Denver, Colorado. Many programs enhance their ability to serve youth by collaborating with other service agencies and government programs in their communities-turning local schools, employment agencies, health professionals, universities, employers, and community centers into allies in the fight against youth homelessness.

About 82 percent of youth who leave transitional living programs, whether they complete them or not, make what are termed "safe exits," moving on to either a private residence or a residential program, rather than onto the street or to a homeless shelter or unknown location. FYSB and its Transitional Living Program grantees are working to raise that percentage even further and to increase the number of youth who complete the programs.

About 82 percent of youth who leave transitional living programs, whether they complete them or not, make what are termed "safe exits," moving on to either a private residence or a residential program, rather than onto the street or to a homeless shelter or unknown location. FYSB and its Transitional Living Program grantees are working to raise that percentage even further and to increase the number of youth who complete the programs.

Now married with steady jobs, Catherine and Dillon are looking for a private apartment. They look forward to their own safe exits and to raising their son in their very own home one day. "It's much harder than we thought to live on our own," Catherine says, citing the many responsibilities of living independently. "We're not ready to leave now, but we will be by the end of the year."

* All names of transitional living clients have been changed in this publication.

1, 2, 3 Steps to Starting a Transitional Living Program

In 2004, the Mendocino County Youth Project began offering a new service to older runaway and homeless youth in its corner of rural Northern California. The organization already offered basic emergency shelter and services to runaway and homeless youth, as well as outreach services for young people who live on the streets, but something seemed to be missing.

In 2004, the Mendocino County Youth Project began offering a new service to older runaway and homeless youth in its corner of rural Northern California. The organization already offered basic emergency shelter and services to runaway and homeless youth, as well as outreach services for young people who live on the streets, but something seemed to be missing.

"We'd see kids at the drop-in center who had no place to go," says Karin Wandrei, the project's director. "They were too old to be foster kids or receive other care, and they were getting into trouble. No one would take them on."

The agency's leaders stepped into the gap, opening the first transitional living program in Mendocino County. They, and others who have launched transitional living programs, have learned that starting a program requires months (sometimes years) of planning, lots of advice seeking, and strong relationships within their communities.

Most often, programs are started by organizations that already serve homeless youth and want to expand their services. Leaders of those agencies seek help from experienced transitional living managers. "Don't try and recreate the wheel-do what you already know works," says Lisa Nally-Thompson, who coordinates runaway and homeless youth services at Project Oz in Bloomington, Illinois.

The number of details that go into opening a transitional living program can seem overwhelming, but don't despair! Based on expert advice from transitional living veterans, some of the main planning steps have been compiled here.

1. Get Ready

Foster Community Ties

If you think your community needs a transitional living program, begin reaching out to people and organizations. You can join an already existing homeless or youth services collaborative or start your own task force.

The collaboration that you join or start might include the following members:

- Youth considered leaders in the community

- Homeless or formerly homeless youth

- A city council member

- Staff from the county’s social services department

- Staff from the city’s foster family agency

- Someone with community needs assessment experience

- Heads of homeless service centers in the area

- Mental health and substance abuse workers

- Property owners

- A realtor

- Local housing directors

- A low-income housing expert

- A lawyer

By making connections to others in your community at this early stage, you lay the foundation for future support.

Where to Get Advice on Starting a Transitional Living Program

- Your regional training and technical assistance provider

- Other transitional living programs

- The resource list in this issue

2. Get Set

A needs assessment—or comprehensive evaluation of the homeless youth population in your community and the kinds of services that would get them permanently off the streets—conducted in collaboration with your community partners will give hard evidence of the need for a transitional living program. It can also convince others, such as funders, policymakers, neighbors, schools, and private businesses, to support your efforts.

When the youth-serving agency WithFriends, Inc., and its local homeless coalition surveyed their community of Gastonia, North Carolina, they found proof of what they already had guessed:“There were lots of homeless kids between the ages of 18 and 21 with no programs, no support, and no Federal entitlement,” says Pat Krikorian, director of With Friends. “Local homeless shelters weren’t meeting their needs. We needed to do something.” Survey results in hand, the coalition got others to agree.

A communitywide needs assessment helps identify the specific population your transitional living program should target: how old they are, what specific needs they have, where they currently sleep, and what services they receive.The assessment also determines how many youth are in your target population and how many you can serve at any one time.

To be useful in appealing to funders and supporters, the assessment must show that the youth you identify need help and that a transitional living program, if sufficiently funded and supported, could help get them off the streets and into productive lives.

Assessing community needs can be a daunting task, so use your connections and network of contacts with diverse expertise to lighten the load.

3. Go

Find the Right Housing

When you've established the need for a transitional living program and identified the population you wish to serve, you're ready to make an important and complex choice: housing.

Research residential models.

"The choice of housing type is probably the biggest issue when planning a transitional living program," says Mark Kroner of Lighthouse Youth Services, Inc., in Cincinnati, Ohio.

"The choice of housing type is probably the biggest issue when planning a transitional living program," says Mark Kroner of Lighthouse Youth Services, Inc., in Cincinnati, Ohio.

You'll need to answer three main questions:

- What type of housing is best for your clients and community?

- Will you own or lease?

- Where will the residences be?

The three most popular residential models are the clustered site, the scattered site, and a combination of the two-the step program. The best model for your transitional living program will depend on the population you wish to serve, your community, and what housing is available (see box).

Clustered-site or group home model. Clients have individual rooms or apartments at one location. Because the clustered-site plan requires a number of youth to be housed in one place, the building tends to be supervised 24 hours a day.

Clustered-site or group home model. Clients have individual rooms or apartments at one location. Because the clustered-site plan requires a number of youth to be housed in one place, the building tends to be supervised 24 hours a day.

Scattered-site model. Clients live in individual apartments at separate locations (either alone or with roommates), and supervision ranges from low (staff dropping in occasionally) to high (staff visiting apartments on a daily or twice-daily basis).

Step, or graduated, model. When clients enter this type of program, they live at residences with high supervision (typically at a clustered site) and advance to a scattered site with more independence and less supervision.

Another important factor to consider when looking for housing is whether to own or lease the property.

Purchasing property. When an organization owns housing, it has a lot of control over clients and their living space. Owning property also means your organization is responsible for renovations and upkeep and for complying with zoning and other property laws.

Leasing residences. Leasing residences allows clients to live in various locations (scattered-site model). Your organization won't have to raise money to purchase a house or be responsible for building and plot upkeep. If you choose to lease, you'll need to decide who will sign the lease.

No matter the type of housing or lease you choose, aim for residences near the following:

- Public transportation, if available in your community

- Potential places of employment

- High schools and community colleges

- Health care clinics and hospitals

Know the housing regulations and zoning laws in the area. And, most importantly, be sure the location is safe.

Find Housing

After you've researched your housing options, it's time to secure housing. Experts agree there's no one right way to do it. For many successful transitional living programs, finding housing is a combination of rigorous planning, nabbing what's available, and trial-and-error.

After you've researched your housing options, it's time to secure housing. Experts agree there's no one right way to do it. For many successful transitional living programs, finding housing is a combination of rigorous planning, nabbing what's available, and trial-and-error.

When the Mendocino County Project started searching for housing, serendipity came to the organization's aid: an employee was related to a property owner who was willing to rent to the project. But Wandrei says it takes more than luck to find the right housing: "We forged connections in our community and used those connections to our advantage."

But often, finding housing isn't as simple as it was for the Mendocino County Project. It took With Friends nearly a year to find a safe place to rent. "Everything was going for us. We had a piece of land. We purchased a house. We received $50,000 from HUD to renovate," Krikorian says. But community protests threw a wrench in their well-laid preparations. "Even after we let [the neighbors] know about our organization's plans, they still didn't want us in their neighborhood," says Krikorian, whose law degree helped her navigate the thorny situation.

With Friends didn't give up. Staff searched until they found a landlord who had "a great heart" and wanted to help the young people the transitional living program was going to serve, Krikorian says. Now that landlord often hires With Friends' clients to do maintenance work and odd jobs. The moral: be persistent.

Get to know the neighbors.

Once you've settled on a neighborhood (or hoods), positive relations with neighbors are key-even before your youth move in. You must prepare your community for the realities of what's going to happen. Notify the police, neighbors, and community groups.

"Be proactive," Kroner says. "Call a neighborhood or city council meeting. Hand out business cards. Set up a 24- hour hotline that people can call with complaints and suggestions."

"Be proactive," Kroner says. "Call a neighborhood or city council meeting. Hand out business cards. Set up a 24- hour hotline that people can call with complaints and suggestions."

Though some neighbors might try to block your efforts to open a transitional living program in their backyard, others will become your biggest boosters, providing support and, if all goes well, terrific public relations.

Take the example of Mendocino County Youth Project staff, who found neighborhood allies by knocking on every door in the small community where they started their clustered-site program about a year ago and speaking to residents about the youth, the program and its goals, and the rules. Since then, one neighbor has enjoyed having young people around so much that he put a basketball hoop in his driveway.

Neighbors supporting young people and giving them healthy, fun things to do: That's a happy ending proponents of transitional living programs would like to see replicated across the country.

Home Sweet Home

Which housing model works best for you and your clients?

Clustered

Clustered

- Best for youth who need daily attention and supervision

- Group counseling, life skills training, and other group services are easier to organize when clients live in one place

- May lead to group and crowd-control issues, as well as neighborhood resistance

- Youth must find a new place to stay after discharge

Scattered

- Best for youth who require less supervision

- Clients can choose a location convenient to work, school, or their social support networks

- Neighbors and landlords won't necessarily know clients are in the program and won't label them as "transitional" or "at-risk"

- Transition to self-reliance is sometimes smoother because the living arrangement resembles the future situation of the youth

Step

- Tailored toward the level of supervision each client needs

- When clients graduate levels, they gain feelings of competence while they are still part of the program

- Staff can work with clients to customize the living situation to their individual needs

See Mark Kroner's Housing Options for Independent Living Programs for more information on types of residences.

Lease Options

The organization signs leases on behalf of clients.

- Landlords may be more willing to lease to an organization than to a young person.

- When one youth leaves, the apartment can go to a new client immediately.

Clients sign their own leases (perhaps with the organization cosigning).

- Youth feel a sense of accomplishment when they sign their own leases.

- Your organization is not responsible for damage done to the residence.

- Clients begin establishing credit and rental references.

- Clients have the option to stay in the residence after they graduate from the program, making transition out of the program easier.

Get to Know the Neighbors

Once you've settled on a neighborhood (or hoods), positive relations with neighbors are key-even before your youth move in. You must prepare your community for the realities of what's going to happen. Notify the police, neighbors, and community groups.

Once you've settled on a neighborhood (or hoods), positive relations with neighbors are key-even before your youth move in. You must prepare your community for the realities of what's going to happen. Notify the police, neighbors, and community groups.

"Be proactive," Kroner says. "Call a neighborhood or city council meeting. Hand out business cards. Set up a 24- hour hotline that people can call with complaints and suggestions."

Though some neighbors might try to block your efforts to open a transitional living program in their backyard, others will become your biggest boosters, providing support and, if all goes well, terrific public relations.

Take the example of Mendocino County Youth Project staff, who found neighborhood allies by knocking on every door in the small community where they started their clustered-site program about a year ago and speaking to residents about the youth, the program and its goals, and the rules. Since then, one neighbor has enjoyed having young people around so much that he put a basketball hoop in his driveway.

Neighbors supporting young people and giving them healthy, fun things to do: That's a happy ending proponents of transitional living programs would like to see replicated across the country.

Tips for establishing good community relationships:

- Invite a realtor, property owner, and someone involved in city housing to join your board of directors or collaborative task force.

- Invite an attorney and a city council member to sit on your community advisory board to deal with zoning laws and housing regulations.

- Foster a positive relationship with your mayor so that he or she supports the program.

Snapshot

FYSB'S Transitional Living Program for Older Homeless Youth

FYSB'S Transitional Living Program for Older Homeless Youth

Purpose: Provides shelter, skills training, and support services to homeless youth ages 16 to 21 for up to 18 months (with an additional 180 days allowed for youth younger than 18).

Eligible Applicants:

- Public agencies-any State, unit of local government, Indian Tribe or Tribal organization, or combination of such units

- Private nonprofit agencies, including community- and faith-based organizations

Services Provided by the Grantee:

Must include, but are not limited to

- Safe, stable living accommodations

- Services to develop skills and personal characteristics needed for independent living

- Substance abuse education and counseling

- Referrals and access to medical and mental health treatment

- Employment assistance

- Education assistance

- Services for pregnant and parenting youth

Funding: A maximum of $1 million ($200,000 per year) for a 5-year project; grantees must provide a non-Federal match of at least 10 percent of the Federal funds awarded.

Duration: Up to 5 years

FY 2004 Funding:

- Total funding appropriated in FY 2004: $40.3 million

- Total grants: 185

- New starts: 36 ($7.2 million)

- Continuation grants: 149 ($29.4 million)

Training and Technical Assistance: Ten organizations receive funding from FYSB to assist youth service agencies that have Basic Center, Transitional Living, or Street Outreach grants from the bureau. One organization serves FYSB-funded projects in each of the 10 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services regions. Go to http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/fysb/content/youthdivision/resources/ttafactsheet.htm to find contact information for the training and technical assistance provider in your region.

Information: Go to http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/fysb for more information on the Transitional Living Program and FYSB's other efforts to assist youth-serving agencies.

Controlled Chaos: Running a Transitional Living Program

Helping young people move out on their own. That's the larger goal of every transitional living program (TLP), and Matt Schnars, who directs the Preparation for Independent Living Program at Haven House Services in Raleigh, North Carolina, always keeps it in mind. "'Independent' means obtaining and maintaining market-rate rental housing," he says. "If we're able to help them get education and employment, that helps them maintain housing."

Sounds straightforward. But the devil’s in the details. Just ask Theresa Nolan,director of runaway and homeless youth services at Green Chimneys Children’s Services in New York City, how challenging it is to teach young people everything they need to live independently in an 18-month program. “Success isn’t necessarily 18 months, a new apartment, a fabulous new life,” she says.

Rather, it’s the smaller successes that make Nolan’s work worthwhile: a young person graduating high school or getting a General Educational Development certificate (GED), moving in with a roommate or family members, getting a job and saving some money, or learning how to listen or how to manage stress and time.

Rather, it’s the smaller successes that make Nolan’s work worthwhile: a young person graduating high school or getting a General Educational Development certificate (GED), moving in with a roommate or family members, getting a job and saving some money, or learning how to listen or how to manage stress and time.

Because chaos often has governed thelives of clients entering a transitionalliving setting, programs must offer some level of stability and structureand emphasize skills building. This article breaks down the main aspects of managing a transitional living program into six areas: screening, mental health and substance abuse counseling, lifeskills training, education and job training, aftercare, and staff issues.

Staff at federally funded transitional living programs take a variety of approaches to addressing each area. Local variables—such as employers willing to hire young people, the choice of public schools, the number of nearby colleges and universities, the cost of rent, and the proximity of support services such as healthcare, child care, and counseling—also lead to differences among transitional living programs.

Screening

Not long ago, Haven House had a single spot open in its transitional living program—and 13 applicants. With many youth applying for transitional housing, how do you decide whom to help? Not only must youth have aneed for housing, life skills training, and education and employment assistance, they must also have the motivation and will to succeed in the program.

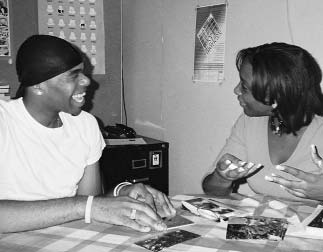

A number of screening methods can help you find youth who fit your program: Requiring youth to interview with program staff, inviting them to dinner with current clients, and giving them tasks like looking for a job or attending a life skills class can give you a sense of how they will do once admitted. But program managers warn against raising too many barriers in front of youth who aren’t yet ready to handle them, so make sure to give youth the support they need even in the screening stage. And remember, sometimes the youth with the most troubled histories work the hardest.

Use your referral system as a first step in screening. Staff at referring agencies, as well as workers in your own organization's emergency shelter, street outreach program, or drop-in center, can tell you whether a youth needs help and how motivated he or she will be if admitted to your program.

Use your referral system as a first step in screening. Staff at referring agencies, as well as workers in your own organization's emergency shelter, street outreach program, or drop-in center, can tell you whether a youth needs help and how motivated he or she will be if admitted to your program.

Use an assessment tool to estimate youth's abilities before they enter the program. Green Chimneys uses a staff-developed checklist that youth must fill out on their own; topics include employment and health histories. Project Oz in Bloomington, Illinois, uses the Ansell-Casey Life Skills Assessment. If a potential client scores only 17 percent, "It's going to be really difficult to expect them to be successful in a scattered-site program," says Lisa Nally-Thompson, coordinator of the agency's homeless and runaway youth services.

Introduce prospects to current clients. After initial interviews with staff, invite prospective clients to a group dinner with youth in your program. "When they're hanging out with the kids over dinner, they'll hear what [the program] is really like," says Christina Alonso, program director for runaway and homeless youth programs at Family and Children's Association in Mineola, New York.

Give youth a taste of the program's requirements. Green Chimneys asks unemployed youth to fill out a job search form and expects them to begin looking for a job during the screening process. At Project Oz, youth must attend three consecutive sessions of the program's weekly life skills classes before they are accepted. "If they miss three classes, it's a good indicator they won't be committed," Nally-Thompson says.

Form an admissions committee that includes representatives from other programs in your agency, or from within your community. Members might include directors or managers of your organizations' programs, former transitional living program clients, and staff from the local public housing authority, local government, your State's Continuum of Care system, court services, mental health services, the local school system, and area universities.

Identify "red flags," the information that might prevent you from admitting a youth into your program. Factors might include a very low life skills assessment score, a pending court hearing, a severe physical or mental disability, a recent conviction for a violent offense, a recent history of fire starting, or an unwillingness to enter drug or alcohol addiction treatment. Such youth should be referred to more appropriate programs that can address their problems. Their admission to a standard transitional living program could disrupt the progress of other clients.

Mental Health and Substance Abuse Counseling

It's hard enough for homeless and runaway youth to learn to live independently, even harder if they also struggle with mental health problems or substance abuse. More than two-thirds of homeless youth served by Administration for Children and Families programs report using drugs or alcohol, and many participate in survival sex and prostitution. Therapy and substance abuse counseling can help youth take steps toward becoming independent and avoiding risky behaviors, all of which support other transitional living goals.

At intake, screen for mental health issues and substance dependence. This helps determine a case plan for the period of time that the youth will be in your care. Understanding what youth are going through is important, says Jean Lasater, director of development at Northwest Human Services in Salem, Oregon: "Our not knowing their struggles at the outset sets them up for failure."

Be clear about your policies on drugs and alcohol. Make sure youth know your program's rules about use of drugs and alcohol in (or out of) their apartments or about staying clean. And state upfront the consequences if they use: Will they automatically be dismissed, or will you discipline them in a particular way?

Include units on drugs and alcohol in your life skills curriculum.

Assess alcohol and drug use regularly. Follow the initial screening with regular assessments of alcohol and drug use. Depending on your philosophy, you may choose to have youth self-report at regular intervals, or you may choose to use random drug testing.

Consider requiring mental health counseling. Some agencies require once weekly therapy sessions for all transitional living youth. At Green Chimneys, youth pay no rent, but instead fulfill a number of weekly obligations, including going to therapy.

Design a program specifically for substance dependent youth. Urban Peak's STAR (Starting Transitions and Recovery) program provides transitional living services to substance dependent youth.

Extend counseling services past discharge. When youth first go out on their own after completing your program, their newfound independence may become daunting-and the mental health issues don't just go away. Continuing counseling helps them make a smoother transition.

Collaborate with a local treatment center. If you cannot afford to hire a full-time therapist or substance abuse counselor, consider contracting with a local health or treatment center

Life Skills

Many runaway and homeless youth have not learned basic skills that most adults, and even other youth, take for granted. Because they've never kept a job, vacuumed, ironed a shirt, cooked a meal, balanced a checkbook, or solved an argument through compromise, life skills training plays an important role in any transitional living program. As Nally-Thompson says, "If you commit to TLP, you commit to life skills." At Project Oz, the mandatory life skills class every Tuesday evening forms the core of the agency's transitional living program from screening through the aftercare stage. Prospective clients must attend three consecutive sessions, and all program participants teach one class before graduating from the program and one after discharge.

Good Will-Hinckley's transitional living program pairs each class lesson with a field lab; for instance, the life skills coach lectures about money management and then takes youth to the bank to open an account.

Good Will-Hinckley's transitional living program pairs each class lesson with a field lab; for instance, the life skills coach lectures about money management and then takes youth to the bank to open an account.

Other programs focus more exclusively on one-on-one and hands-on learning. Rather than teaching life skills in the class room, Haven House Services case managers work with each client individually by using a curriculum tailored to the youth's needs and guiding him or her through daily tasks. "The kids learn by doing," Schnars says.

Create an individual case plan for each youth. The plan might be based on an assessment tool such as the Ansell-Casey Assessment or one created by your agency, on interviews with the young person, or a combination. Repeat the assessment or revisit the youth's goals at predetermined intervals, for instance at intake, 6 months, and discharge.

Tailor your life skills curriculum to your clients' needs. In addition to consulting pre-written life skills materials, such as those available from Casey Life Skills, ask youth what would benefit them.

Use the day-to-day tasks of independent living to teach youth practical skills. Finding an apartment, signing a lease, changing a light bulb, paying rent, buying groceries on a budget, cleaning a bathroom, and doing laundry-with the guidance of a caring staff member or mentor-are all things youth learn through experience. When youth first move into their apartments, tell them to go to three neighbors and borrow eggs; the task "roots" them in their new surroundings and teaches them the value of asking for help and building relationships, Nally-Thompson says.

Help youth ease into the responsibility of paying rent by shouldering part of the burden. Use an incremental system of requiring rent, giving youth stipends toward all or part of the cost. Stipends decrease monthly or quarterly until youth are paying the full amount on their own. Or you might adjust youths' rent according to their income; Northwest Human Services requires working youth to pay $200 or 40 percent of their income (whichever is less) toward rent.

Encourage savings and sound money management. Many programs require or recommend that youth make regular deposits to a savings account. At Family and Children's Association, youth keep a dollar for every hour they work; the rest goes in a bank account in the client's name. "When they leave our program, they need to be a lot further than one paycheck away from homelessness," Alonso explains. The philosophy has worked: several youth have saved more than $10,000 while in the program. Other programs have less stringent savings requirements. Northwest Human Services asks youth to save 10 percent of their incomes in personal savings accounts.

Find ways to infuse energy into life skills education. "You'll bore them to death with too many sessions, so you've got to bring outside speakers," Nally-Thompson says. Speakers in her program's sessions have included firefighters, a human resources manager from a local employer, a renter's insurance agent, and an admissions representative from a local college. Role playing and discussion also can enliven class.

Use one-on-one sessions between youths and their case managers to work on skills the youth needs or wants to acquire. This approach can supplement classroom and group learning.

Schedule a weekly or monthly group dinner at which youth and staff cook together. Shared meals can work in group homes and scattered-site apartments alike. Good Will-Hinckley's scattered-site program rotates the monthly dinner among participants. "It gets them in the habit of being a good host and handling company," Hinckley-Gordon says. The meals also strengthen connections among participants and staff.

Use rewards and incentives to mark progress. Residents of Family and Children's Association's transitional living program helped design a system through which they earn perks, such as pushed-back curfews, as they achieve milestones-sewing a button, getting a job, preparing a weekly meal plan. Youth also receive rewards for things such as saving $1,000 (two movie tickets and a curfew extension) and acing a test (two overnight privileges). Conversely, when youth, say, miss school, they create their own punishment. "They might say, 'I'm going to read a book,'" Alonso says.

Reward youth for completing the program. That might mean a graduation party with cake and ice cream, or something more substantial: Several agencies give young people who have completed their programs a nest egg by paying back part or all of the money they have collected from the clients for rent.

Popular Topics

Popular topics in many life skills curricula include:

- Getting a job

- Job maintenance skills

- Value of being on time

- Negotiation skills

- Budgeting

- Health and nutrition

- Hygiene

- Landlord-tenant relations

- Stress and anger management

- Dealing with change

- Setting goals

- Maintaining personal boundaries

- Abstinence education

- Domestic violence

- Drugs and alcohol

- Sexually transmitted diseases

- Pregnancy prevention

- First aid and CPR

- Units specifically for pregnant and parenting youth, such as parenting, nutrition during pregnancy

- Units on handling harassment and job discrimination

Life Skills Activity: Scavenger Hunt

This scavenger hunt can be used either as a group competition or an individual challenge that supports life skills education for transitional living program participants. It was adapted from a document provided by Project Oz, a youth services agency in Bloomington, Illinois.

This scavenger hunt can be used either as a group competition or an individual challenge that supports life skills education for transitional living program participants. It was adapted from a document provided by Project Oz, a youth services agency in Bloomington, Illinois.

| NAME: |

|---|

- Bus schedule

- Checking or savings account application from a bank or credit union

- Employment application from anywhere

- Sale circular from a grocery store

- Valid library card or library card application

- Change-of-address form from the post office

- Car dealer advertisement

- Information packet from a bank on accounts they offer

- Abstinence education brochure

- Current list of support groups offered in our area

- Most original independent living resource you can think of

- Employment section of the newspaper

- Driver's license handbook

- Brochure from a museum

- Application for admission to a vocational school, college, or GED program

- Pamphlet on sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) or AIDS

- Insurance company brochure

- Social Security card or application for Social Security card

- On a piece of paper, your name, address, and phone number and directions on getting to your apartment from the transitional living program office

- List of community health clinics from the health department

- On a piece of paper, your best advice on how to save money

- High school diploma or GED

- Business card of someone who would be a good contact

- Name of your doctor and his or her phone number

- Birth certificate or information on how to get a copy of your birth certificate

- Emergency contact list

- Your landlord's name and phone number

- Legal services brochure

- Valid form of identification, wuch as driver's license or State ID

- Medical card or information on how to pay for medical services

- Family heirloom or something special from your childhood

- Picture of you with family or friends

Education and Job Training

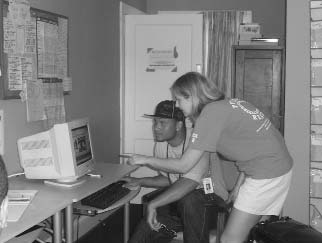

Youth need jobs in order to pay their rent, and they need education to prepare them for the work world and adult life. Green Chimneys asks unemployed youth to start looking for a job even before they are admitted. Other programs require youth to combine employment and education to achieve at least 40 hours a week of "productive time"-time in which they are learning, working, or commuting to school or work. "We try to teach them the importance of staying busy," Hinckley-Gordon says.

It can be tough to find schools that will accept runaway and homeless youth; transitional living staff should know that the Federal McKinney-Vento Act requires public schools to admit homeless and unaccompanied youth without delay, even if youth do not have proper documentation or proof of guardianship.

It can be tough to find schools that will accept runaway and homeless youth; transitional living staff should know that the Federal McKinney-Vento Act requires public schools to admit homeless and unaccompanied youth without delay, even if youth do not have proper documentation or proof of guardianship.

The level of success program managers have convincing youth to continue their education past high school may depend on the availability and diversity of local higher education options, the local job climate and the necessity of a college degree, and a youth's interest in college. In Bloomington, Illinois, where State Farm Insurance employs a large percentage of inhabitants, Nally-Thompson encourages youth to attend college. "They just need those skills," she says. "If you want to stay in town, the biggest employer is State Farm. If you want to work at State Farm, you have to have a degree."

Create an individual case plan for each youth, with his or her help. "The goal could be getting your GED in 6 weeks or 2 years" depending on the youth's situation and needs, Van Leeuwen says.

Develop relationships with local public schools. Program managers say meeting face-to-face with school administrators can make it easier to place youth in schools. Alonso also suggests that transitional living staff familiarize themselves with runaway and homeless youth law, including the McKinney-Vento Act. Schnars says many of Haven House's youth attend a charter school with which the agency cooperates because the school has more flexible hours than other area schools and can accommodate working students.

If possible, make it easier for youth to attend the school of their choice. Scattered-site apartments allow youth to live near the school they are already attending, if they choose.

Help youth find instruction to prepare for the GED. Some agencies offer GED training on site, while others provide it to youth through an affiliation with an education center nearby. At Haven House, volunteers from Meredith College tutor youth who are taking an online GED course.

Explore alternative education options in your community. Alternative schools often are tailored to the needs of students who have had academic or discipline problems, as well as those who struggle with the traditional school routine.

Help youth navigate their post-secondary education options. Some youth may do better starting out in 2-year colleges and moving on to a 4-year institution. She adds that some youth do well in college because it offers more flexibility than high school. Nally-Thompson helps youth get around financial aid requirements that demand a copy of parents' W-2. "We have relationships with the university financial aid office and ways to get around it," she says.

Establish a scholarship fund. Family and Children's Association offers educational scholarships of up to $1,000 to alumni of its residential programs.

Find vocational training that matches youths' interests. "If a child is not interested in education, then we try to sell them on a skill," Alonso says. One youth in her transitional living program got an apprenticeship as an electrician. Others have studied technology and cosmetology, and Alonso stays closely connected to local vocational programs. Green Chimneys has a relationship with a security guard training institute, Nolan says, adding, "I'm definitely willing to pay for training to help a young person get a job."

Make connections with major employers in your area. Nally-Thompson invites State Farm human resources staff to speak to Project Oz youth about getting a job at the insurance company.

Give youth the skills they need to get and keep a job. Include job searching, interviewing skills, communication skills, work ethics, and other topics related to professional life in your life skills curricula.

Make sure your staff has the expertise to help youth find employment. If you can't afford a dedicated job counselor, invest in training for your case management staff.

Invite program graduates to speak to current clients about their careers.

Collaborate with local school-to-work programs and employment agencies. Organizations to consider include Job Corps, AmeriCorps, YouthBuild, job shadowing programs, and local employment centers.

Offer youth employment or volunteer opportunities within your organization. Northwest Human Services started a program called KANZ for Kids in which local businesses donate used cans and bottles; youth who can't find work help oversee the program, pick up the cans, sort them, and turn them in for money that benefits the agency.

Aftercare

Your work doesn't end when a youth graduates from your program. In fact, your relationship with youth in the months after discharge can be just as important as all the services you provide up till then. But despite its importance, aftercare, or monitoring youths' progress after discharge to be sure they transition successfully to independent living, can be tricky. Sometimes, youth leaving transitional living programs don't want to stay in touch; they want to be on their own, Hinckley-Gordon says. And often, youth move around a lot, so agencies have difficulty keeping contact information up-to-date.

Former clients tend to visit the transitional living program in times of need, Nolan says. "It's like when kids grow up and leave home," she says. "When they lose their Metro card or need help with their job, they come back to ask for financial or emotional support. . For some of them, we're all they have." Transitional living staff are happy to provide that support. "It costs $4,000 to get a kid off the street," Van Leeuwen says, "so, I would rather help with rent."

Start planning aftercare as soon as possible. "We do discharge planning from the minute they walk in the door," Nally-Thompson says. That means setting goals early on that will allow youth to sustain independence when they leave the program.

Emphasize that youth talk to you before they leave the program, even if they are dropping out. Catching dissatisfied youth before they rush out the door can give you one last chance to find them a place to stay, offer them food or clothing, and listen to their concerns. Even a few minutes' counseling can prevent an unsafe exit to the streets.

Keep the doors open. Let youth know they are welcome back, regardless of how they were discharged, and tell youth who don't finish the program that they can try again when they are ready. Most agencies say youth do visit in the first year or so after their discharge or graduation from the program; they come to talk or ask for financial help.

Keep the doors open. Let youth know they are welcome back, regardless of how they were discharged, and tell youth who don't finish the program that they can try again when they are ready. Most agencies say youth do visit in the first year or so after their discharge or graduation from the program; they come to talk or ask for financial help.

Extend services beyond discharge. Project Oz and Northwest Human Services both provide case management 6 months past discharge. At Haven House, discharged youth can continue to use the organization's drop-in center as well as counseling and employment services. Offer to help youth pay for services at other agencies, if you can.

Increase staff retention and stability. Youth return to see the people they know, so efforts to reduce staff turnover can also have a positive effect on aftercare.

Use e-mail to stay in touch. Urban Peak is putting together an online tracking system to keep track of former clients. Vstreet, a Web site that teaches life skills to youth, allows registered agencies to set up e-mail accounts for their clients. Nally-Thompson uses Vstreet e-mail to stay in touch with former clients. Many free e-mail services exist; encourage youth to set up their own accounts and give you their addresses before they leave your program.

Give youth a reason to come back. Project Oz requires youth to teach a life skills class after they complete the transitional living program. Youth also return as guest lecturers. Good Will-Hinckley's former clients visit staff members' homes for holiday meals and attend monthly community events on the agency's campus. The organization also hosts an annual "KUM BAK" weekend for alumni.

Offer financial incentives for alumni to stay in touch. Family and Children's Association's scholarship for former clients is one reason that transitional living program graduates keep in touch with the agency.

Staffing

The staff members you hire can make a big difference in your success with young people. "I believe that having a really competent person can sell the program and keep the child motivated," Nally-Thompson says. She adds: "But you have to keep staff motivated, too."

The demands of working in a transitional living program-long hours, high-maintenance clients, too much paperwork, lots of time on the road in scattered-site programs-can lead to staff burning out or leaving. Combating burnout and turnover benefits youth as well as employees: staff longevity can provide youth with stable, long-term relationships, which are one key to youth progress.

Involve youth in hiring staff. At many programs, youth sit on hiring committees or interview candidates for new positions.

Be flexible. Theresa Nolan of Green Chimneys says flexible work schedules are a key to keeping staff from crumbling under the weight of too much stress. In addition, her staff rotate on-call duty among them.

Keep caseloads manageable. It may be hard to do, but preventing staff from becoming overloaded with too many cases allows them more time to talk to youth who need a sympathetic ear, to handle drop-in visits from former clients, and to breathe.

Team up. Assigning a primary and secondary staff member to each case can give staff backup on hard cases, and youth don't have to be shifted around when one staff member needs to take time off for whatever reason.

Offer training. Give staff opportunities to travel to conferences and seminars. When possible, offer onsite training in issues you think need addressing, such as youth development. Not only is the training essential, but taking a break from daily duties also does staff good.

Get help. Interns, volunteers, and mentors can lighten your load. Project Oz has seven to nine interns at a time from the social work department of a nearby university. The interns get class credit, and staff get a break from tasks like filing, taking youth grocery shopping, and driving youth to work when they miss the bus. Mentors and volunteers can spend time with youth when staff are busy.

Hire remote staff. If you run a scattered-site program over a large geographic area, you might consider basing a few staff members in other locations, to relieve case workers of long drive times.

Communicate. Meet weekly. Debrief daily.

Have fun. Sometimes staff need a break from the hectic pace of their work-time to build relationships with each other. Every few months, Nally-Thompson takes her staff out for pizza and a fun activity, like bowling, followed by trust-building or other exercises.

Shaking the Sofa Cushions, or How to Find Funding

Funding-finding it and sustaining it-is a huge part of starting and maintaining any program. Just as there is no one right way to start and maintain a transitional living program, there is no one right way to raise money. However, organizations successful at raising and keeping funds tend to have some strategies in common.

Funding-finding it and sustaining it-is a huge part of starting and maintaining any program. Just as there is no one right way to start and maintain a transitional living program, there is no one right way to raise money. However, organizations successful at raising and keeping funds tend to have some strategies in common.

- Connect: The organizations forge connections with diverse groups and individuals.

- Get support: They tap into local and statewide networks for support.

- Think creatively: Staff think and act creatively to raise funds. (See tips below.)

- Work flexibly: Administrators conduct fundraising activities, and the program in general, with an open mind. They know how to roll with the punches.

- Know the rules: The organizations know and follow funding sources' guidelines and regulations well.

Show Us the Money

Common funding streams for transitional living programs include:

Common funding streams for transitional living programs include:

- Federal: Runaway and homeless youth programs and HUD

- State: Independent living, housing, social services, and child and family welfare

- City and county: Social services funds

- Private: Foundations, corporations, individuals

- Local faith-based organizations

Put on Your Thinking Cap

Here are some creative tips for raising funds or getting in-kind donations:

- Form creative alliances with food banks.

- Ask retail stores for items or discounts.

- Look for support from your community other than cash, such as volunteer work or in-kind donations.

- Use other, larger agencies' offerings, such as mental health or education services.

- Have adult volunteers, clients, and other youth participate in grassroots fundraising activities and staffing.

- Solicit property, furnishings, and volunteer services from faith-based groups.

- Include a program wish list in your agency's newsletter.

- Ask local restaurants and cinemas to donate gift certificates for clients.

- Find corporate groups willing to do building renovation or landscaping work.

Get Help

Most important, seek advice from others. Talk to your Administration on Children and Families Regional training and technical assistance provider. Contact and, if possible, visit successful transitional living programs.

Evaluation on a Dime

You and your transitional living program staff work yourselves to the bone. You know in your gut that your effort makes a big difference to your clients. Many of them are getting jobs, graduating from high school, moving out on their own. But you don't have quantitative proof of your program's positive effects.

You and your transitional living program staff work yourselves to the bone. You know in your gut that your effort makes a big difference to your clients. Many of them are getting jobs, graduating from high school, moving out on their own. But you don't have quantitative proof of your program's positive effects.

"Evaluation is the ethical thing to do." says David Pollio, an associate professor at the George Warren Brown School of Social Work at Washington University in St. Louis, who studies outcomes for runaway and homeless youth: "If you don't do evaluation, you don't know if what you're doing works."

The following tips were compiled from conversations with Pollio and with Jamie Van Leeuwen, director of development and public affairs at Urban Peak, a youth-serving agency in Denver, Colorado.

- Don't jump off the deep end. Don't begin with a long-term, fancy study. Start off small.

- Know what you're evaluating and why. When you're collecting data, stop and ask yourself why you're collecting it. Form focus groups-one composed of management, another of staff, and a third of youth-to answer questions about what kind of data will be useful and what purpose it will serve.

Surveys don't have to be complicated. Staff can work together to write simple surveys. Van Leeuwen, who is working on a doctorate in public policy, regularly polls runaway and homeless youth in Urban Peak's care. The results help the agency's staff to pinpoint areas that need improvement. For instance, youth complained that staff often were too busy to talk, so Urban Peak is looking at its case managers' loads to find ways to reduce the time they spend on less important tasks. The agency also is recruiting more mentors, so kids always have someone to talk to.

Surveys don't have to be complicated. Staff can work together to write simple surveys. Van Leeuwen, who is working on a doctorate in public policy, regularly polls runaway and homeless youth in Urban Peak's care. The results help the agency's staff to pinpoint areas that need improvement. For instance, youth complained that staff often were too busy to talk, so Urban Peak is looking at its case managers' loads to find ways to reduce the time they spend on less important tasks. The agency also is recruiting more mentors, so kids always have someone to talk to.- Involve youth. At Urban Peak, youth help draft surveys and suggest additions. Van Leeuwen also pilot tests the surveys on two or three young people. "The more you can involve them, the better," he says. "The experts on homeless and runaway youth are your homeless and runaway youth."

- Build evaluation into daily tasks. You probably already interview clients at intake and discharge; simply standardize those processes, and you have an evaluation tool.

- Collaborate, collaborate, collaborate. "It's almost impossible for an agency to design a sensitive evaluation without collaboration," Pollio says. Because most agencies don't have staff with expertise in evaluating programs, conducting surveys, and compiling statistics, youth service organizations can enlist the help of professors from local colleges or universities. College students can also be great collaborators, working as unpaid interns who gather and process data.

- Be prepared for what you might find out. Open yourself up to constructive feedback. Distinguish between the kid who is having a bad day and the kid who says his or her case manager doesn't listen.

- Use what you learn. "If it's going to sit in your desk, it's not worth collecting the data," Van Leeuwen says. Managers should meet with staff after an evaluation and come up with an action plan for improving programs and processes over the next 6 months.

- Take advantage of the Runaway and Homeless Youth Management Information System (RHYMIS). Organizations that receive FYSB grants are required to report on their programs using the Bureau's management information tool, but programs can also use RHYMIS to track youth whose care is paid for by non-FYSB grants. In addition, even programs not receiving FYSB funding can track their progress using RHYMIS and its support hotline. For more information, go to http://extranet.acf.hhs.gov/rhymis.

Transitional Living Resources

Publications

Publications

- Assessing Outcomes in Youth Programs: A Practical Handbook.

Authors: R. Sabatelli, S. Anderson, and V. LaMotte. 2001. Available at http://www.opm.state.ct.us/pdpd1/ grants/jjac/jjacpublications.htm.

This handbook gives practical advice on evaluating youth programs using Positive Youth Development outcomes measures. - Covenant House Transitional Living Manual

Author: Covenant House New York. No date. Available at http://www.covenanthouse.org.

A step-by-step guide to starting and running a transitional living program, based on the experiences of the Rights of Passage program at Covenant House New York. - Housing Options for Independent Living Programs

Author: M. Kroner. 1999. Available from online booksellers.

This book looks at the variety of housing arrangements that transitional and independent living programs may use, the challenges facing program managers, and ways to measure success. - Moving In: Ten Successful Independent/Transitional Living Programs

Editor: M. Kroner. 2001. Available from Northwest Media, Inc., 362 West 12th Avenue, Eugene, OR 97401; (541) 343-6636; http://www.northwestmedia.com/il/movingin.html.

Staff of 10 transitional and independent living programs across the country describe what makes their programs work. - Unlocking the Potential of Homeless Older Adolescents: Factors Influencing Client Success in Four New England Transitional Living Programs

Editors: M. Wilson and D. Tanner. 2001. Available at http://www.nenetwork.org.

In this report, FYSB's Region I training and technical assistance provider, the New England Network for Child, Youth & Family Services, investigates the factors that have led to success at four federally funded transitional living programs.

Web Sites

Web Sites

- Casey Life Skills

http://www.caseylifeskills.org

Casey Life Skills offers a free online life skills assessment tool as well as a guide that helps youth workers design a curriculum tailored to their program and their youth population. - National Clearinghouse on Families & Youth

http://ncfy.acf.hhs.gov

The National Clearinghouse on Families & Youth (NCFY) Web site has links to programs of the Family and Youth Services Bureau, as well as to other Internet resources for youth-serving professionals. NCFY's online literature database contains abstracts of thousands of youth development resources. - National Center for Homeless Education

http://www.serve.org/nche/

The National Center for Homeless Education's Web site includes a list of resources by State. - National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty

http://www.nlchp.org

This site has a wealth of information on the rights of homeless people, including homeless and unaccompanied youth, and a helpful guide called "Legal Tools to End Youth Homelessness." - National Resource Center for Youth Services

http://nrcys.ou.edu

A great general resource for all types of youth-serving agencies. Look here for trainings, information about Positive Youth Development, and creative funding ideas.