Fall 2005, Vol. 37, No. 3

The "Z Plan" Story

Japan's 1944 Naval Battle Strategy Drifts into U.S. Hands

By Greg Bradsher

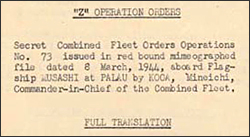

Left: Adm. Mineichi Koga. (80-JO-63354) Right: detail of the title page of the ATIS-translated copy of the Z Plan. (Records of General Headquarters, Far East Command, Supreme Commander Allied Powers, and United Nations Command, RG 554 [full page])

At 10 p.m. on March 31, 1944, two Japanese four-engine Kawanishi HSK2 flying boats (patrol bombers) set off from Palau in the Caroline Islands to Davao, Mindanao, in the Philippines, normally a three-hour flight due west. One of them carried Adm. Mineichi Koga, commander in chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet. Another carried Koga's chief of staff, Rear Adm. Shigeru Fukudome.

Carrier strikes by American forces in late March prompted Koga to abandon Palau as his headquarters. Now he planned to set up operations at Davao, where he would prepare the Japanese Combined Fleet for operations against the American Navy in a great decisive battle.

Koga had become commander in chief of the entire Japanese fleet on April 21, 1943, replacing Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto, who had died three days earlier. He took over his new duties at Truk, the main Japanese mid-Pacific naval base in the Caroline Islands on April 23, with the Musashi serving as his flagship.

Fukudome, who took over as chief of staff in May, had known Koga for a number of years and considered him a conservative and cool officer who thought logically but was strong willed. These traits were evident in the plans he was shaping for battle with the American fleet. From the very beginning, Koga insisted that their one chance for success lay in a decisive naval engagement.

Koga's strategy was spelled out in an August 25, 1943, document that the Japanese called the "Z Plan." It outlined defensive plans against Allied attacks on Japan's South Pacific possessions and made provisions for engaging the American fleet in a decisive battle. In early February 1944, Koga won approval from the General Staff to modify the plan by redistributing Japanese forces around a revised "last line of defense." He also won approval to command the fleet at Truk rather than staying in Tokyo.

While Koga was still in Tokyo, though, American aircraft attacked Truk on February 16–17 and sank several Japanese warships and merchant ships and destroyed upwards of 275 aircraft. Truk was now too vulnerable. On February 23, Koga boarded the Musashi and set sail to Palau in the western Carolines. From Palau, some 1,500 miles east of Truk, he would set the Z Plan into motion.

Koga's strategy as outlined in the Z Plan would never be carried out by the commander in chief, or by anyone else successfully. This is the story of how the Z Plan drifted into American hands in one of World War II's greatest intelligence victories, leading to a crushing defeat for Japan in the Southwest Pacific in 1944.

When Koga proceeded to Palau, he announced his decision to hold the line of defense between the Marianas and Palau until death. Should that line be lost, he believed, there would be no further chance for Japan. To that end, he chose two land bases from which he would guide operations. If the next strike should come north, he would command from Saipan. If the strike should be directed southward, he would command from Davao. Whichever the direction, he was determined to make his last stand and consequently to die at either Saipan or Davao in defending this line. Koga chose land bases from which to guide the operation because navy carrier-based air groups were severely depleted, and he calculated that replacements would not be ready until May 1944. The new strategy used land-based air forces as the main strength, with the fleet units cooperating as fully as possible.

Once at Palau, Koga and his staff refined the Z Plan, issuing a final draft version to the fleet on March 8 (Combined Fleet Secret Operations Order No. 73). It would commit all remaining Japanese naval power to one last major battle. Two weeks later, Koga's staff produced a paper entitled "A Study of the Main Features of Decisive Air Operations in the Central Pacific." It suggested aerial tactics that might be used during the decisive battle to counter the American naval offensive and destroy the U.S. Pacific Fleet. It was detailed and meticulous, spelling out current status and projected strength, plus where Japanese surface and air strength was to be deployed by the end of April. Koga expected the Americans to show up in strength any time after the first of April. He believed that once the American fleet broke into the Philippine Sea, by way of the Marianas or the Palau Islands or New Guinea, the Japanese Combined Fleet would meet them in full strength. He then set about consolidating the bulk of his forces, obtaining more airplanes, and training replacement pilots.

During the mornings of March 28 and 29, Japanese scouting planes informed Koga that the American fleet appeared to be heading toward the Palau Islands. By noon on March 29, Koga was convinced that the Americans would attack the next day. He quickly moved his command ashore, with Admiral Fukudome taking charge of the leather pouch containing the Z Plan. That afternoon Koga ordered that all warships and merchant ships away from Palau. Shortly after the Musashi left the Palau harbor and entered the Pacific around 5:40 p.m., she was torpedoed. Although the damage was not major, the ship was not in condition to fight and set sail to Japan for repairs.

Koga did not dwell long on the fate of his flagship, for at dawn on March 30 the American fleet, only 75 miles southwest of Palau, launched an aircraft attack. Japanese defensive efforts were ineffective. Later that day, Koga learned that American transports were heading westward from the Admiralty Islands. He and Fukudome concluded that the attack was not intended against the Marianas but against the western Carolines, which would constitute the southern part of the area to which Koga referred as the line of defense. They believed the Americans intended a landing in western New Guinea. If this was case, Koga did not desire to be isolated at Palau, and he decided to withdraw the next night to Davao, 600 miles to the west.

At night on March 31, Koga boarded a flying boat bound for Davao. For security reasons, Fukudome, accompanied by 14 staff officers, flew in a second plane.

As Koga and Fukudome ferried out to the flying boats, Koga said to Fukudome "Yamamoto died at exactly the right time," and added, "Let us go out and die together." They shook hands, said their goodbyes, and boarded their respective planes. At around 10 p.m. the planes took off for the Philippines. Fukudome carried in his briefcase the Z Plan documents (it was a bound copy, the red cover bearing a "Z"), an air staff study of carrier fleet operations, rules for code use, place-name abbreviation list, and other signals information. A third aircraft, much delayed, took off at 3 a.m. on April 1 with communications and clerical staff with their top-secret codes aboard. It would be the only one of the three planes to reach Davao.

A Japanese "flying boat" similar to the one that carried Admiral Koga. (80-G-227384)

Koga's plane ran into an enormous tropical storm front and crashed into the Pacific. There were no survivors. Fukudome's plane tried to skirt around the storm. When it appeared that Davao was unreachable, Fukudome suggested the plane head north for Manila, as they had enough fuel to reach that city. Headwinds impeded the plane's flight and forced greater consumption of fuel. Manila was now out the question, but Cebu Island was six miles away. The exhausted pilot put the plane in a steep approach to land but misjudged the altitude. Fukudome, fearing the plane would crash, grabbed the controls from the pilot to gain altitude. The plane overresponded, and within seconds it hit the water and settled into the Bohol Strait, about two and a half miles from shore. It was about 2:30 a.m.

The remaining fuel in the wing tanks exploded, and flaming aviation fuel spread across the sea, encircling the wreckage. As the plane started sinking, Fukudome, with an injured leg, freed himself from the wreckage. He grabbed a seat cushion as a float and tried to get as far away as he could from the plane, flames, and fuel on the surface, not bothering to look for the portfolio with the Z Plan documents. Floating around him were 12 survivors. Twelve others died. As the plane sank, Fukudome believed the Z Plan documents must have gone down with the plane. His immediate concern was survival.

At daylight, Fukudome saw a familiar landmark on shore and felt it was fairly safe territory, only about six miles south of the Japanese headquarters for the central Philippines at Cebu City. Despite the presence of guerrillas operating in the area, he believed he would be safe if he could reach shore. Some of the younger members of the crew moved ahead and even started singing.

Around 11 a.m., at the shoreline at Magtalisay, a small village near the town of San Fernando, two residents of the village heard the singing and saw the men swimming to shore. They grabbed two small fishing canoes and paddled toward them. Another Filipino joined in the rescue until he realized that the two swimmers he came upon were Japanese. He quickly jumped into the water, pushed his boat toward them, and swam back to shore. These two Japanese jumped in the unoccupied boat and starting rowing away from the Filipinos.

But 10 others—Fukudome's aide, the pilot and co-pilot, a warrant officer, and six petty officers and sailors—were pulled out of the water and made it to shore. While some of the Filipinos wanted to shoot them, others believed they should be taken captive and interrogated for information. The latter view prevailed, and the survivors were quickly herded off the beach into the hills. The party then started toward Barrio Balud (barrio being the term for an urban district or quarter).

As Fukudome continued swimming toward shore, two or three canoes came out to rescue him, but he hesitated because he was not sure whether they were friends or enemies. Near the limit of his physical strength, he finally decided to take a chance and be rescued.

Upon reaching shore, Fukudome was quickly seized by five or six Filipinos and herded toward the mountains. He feared he would be killed, but once his captors realized the plane had not come to attack the island or the natives, they offered medical treatment. The Filipinos informed him that he would eventually meet up with the other survivors. At this point, Fukudome realized that not only was he a prisoner of war, but he was first flag-rank officer in Japanese history who had allowed himself to be captured by the enemy.

While the survivors were on their way from Barrio Balud to Barrio Basak, a Japanese floatplane buzzed the villages looking for the survivors. The two Japanese who had paddled off had made their way to the Japanese army garrison at a nearby town and told officials of the crash and survivors.

The Japanese launched a massive air search for Koga's plane and survivors from the Fukudome aircraft as well as "important documents" that may have drifted ashore. They indeed had reason for concern, for the documents did not sink with the plane but survived in the box in which they were contained—now bobbing in the waters off Cebu.

On the morning of April 3, Pedro Gantuangoko, a shopkeeper at Perilos, a village farther down the beach from Barrio Magtalisay, saw an object floating in the water just offshore. He had a neighbor, Opoy Wamer, take his boat out and fetch it. Wamer opened the slimy, oil-covered box and discovered a red leather portfolio. He believed its contents must be important. He was correct. Gantuangoko told Wamer to leave the box in the boat and keep the boat anchored about two dozen yards off the beach, then wait until dark to retrieve the box and hide it at home. At noon that day, Japanese soldiers appeared along the beach looking for the survivors and anything that might have washed ashore. The boat went unsearched.

That night the two Filipinos retrieved and inspected the box. Inside the portfolio they saw a half dozen packets of wet papers, some quite thick. They laid the documents on the split-bamboo floor to dry. They kept a pouch containing small nuggets of gold as the spoils of war. The next day, April 4, they took the documents to another house, where the documents were allowed to dry another day. That evening they put the documents back into the box and buried it.

At the same time, the survivors (one had been killed at Barrio Basak trying to escape) of the crash and their Filipino captors climbed deep into the hills above San Fernando, heading nearly due north toward Barrio Tabunan, the headquarters of the Cebu Area Command (CAC), a guerrilla organization composed of several thousand Americans and Filipinos. In command of CAC was U.S. Army Lt. Col. James M. Cushing, who had been a mining engineer in the Philippines before the war.

Making long detours to avoid Japanese patrols, the party eventually reached a rest area and guerrilla aid station near Caloctogan. Fukudome, who had been carried on a primitive stretcher for nearly a week, was very weak with festering wounds and a fever of about 104ºF. Some of the other survivors were also in bad shape. Cushing's personal doctor treated the wounds of the captives to reduce the risk of further infection.

In Tokyo, the Japanese High Command was becoming greatly concerned about Admiral Koga and the documents. It sent out a message stating that Koga and his staff were missing and that the Navy was investigating the situation, but the addressees were told to keep the affair secret and minimize the number of people who knew about it. Future messages would refer to the affair as the "Otsu incident."

Americans intercepted and decoded the message. Within hours, it was at the Far East desk of naval intelligence in Washington, D.C. However, it would take a while for the information to find its way back to Gen. Douglas MacArthur's Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA) headquarters in Brisbane, Australia.

Meanwhile, the Japanese in the Philippines began a ruthless campaign to uncover information about Koga and the missing documents. Lt. Col. Seiiti Ohnisi, Japanese commander at Cebu City, had his soldiers burn villages and kill hundreds of civilians.

They made a concerted search in Gantuangoko's village. Two hundred troops combed the beaches and the village. They called together all the villagers and asked if any had seen a box. They all said no. The troops then searched each house. They found nothing but were certain that the box was in the vicinity. Japanese navy tide and current experts believed the box had probably washed ashore in the area. They even took similar boxes out to the crash site and let them float to shore. Always, the boxes floated to Perilos.

The next day, the soldiers returned and again searched the village. Gantuangoko, concerned about the buried box near his house, decided to get rid of it. He contacted a local guerrilla and gave him the box and even the gold, wanting to wash his hands of the whole affair. The next day the Japanese began interrogations again and offered a reward of rice and cloth to any villager who provided information about the missing box. No one said a word. Perilos was then burned.

At some point, probably April 9 or 10, the box, with its red portfolio of Japanese military secrets, was sent to Cushing by way of the guerrillas.

On April 8, Cushing learned that captives from a crashed seaplane would shortly arrive at his camp. He radioed SWPA headquarters in Brisbane that 10 Japanese prisoners were en route to his headquarters and asked what actions should be taken, adding that "constant enemy pressure makes this situation very precarious." He promised to send further information from the prisoners. This message was read by Col. Courtney Whitney, the chief of the Philippine Regional Section of the Allied Intelligence Bureau, on April 9. He radioed Cushing that that the disposition of the prisoners had to be in accord with the rules of land warfare and offered to help facilitate the removal of the captives to another island if necessary.

Shigeru Fukudome. (80-JO-63419)

When Fukudome and his colleagues showed up at Cushing's headquarters on April 8 with their guerrilla captors, he and two other Japanese captives were immediately admitted to the base hospital. Later, Cushing informed the captives that he was in control of Cebu and that as long as they were with him, they were safe. He told them that he knew they came from the crashed seaplane and asked who they were and what their mission was.

Comdr. Yuji Yamamoto, Fukudome's aide, who spoke some English, provided evasive answers. During the questioning, Cushing learned that one of the Japanese, Fukudome, was a flag officer. He was led to believe he was Gen. Twani Furomei, commanding officer of land and sea forces in Macassar, Celebes. That evening Cushing again met with the captives. The "general" joined in the conversations, speaking fluent English. (Cushing suspected the "general" really was not who he said he was. After the war, Fukudome said that Cushing used to address him as general and "I did not think it necessary to correct him as to the title.")

The next day, Japanese troops, knowing Cushing held prisoners, closed in on his headquarters. Learning this, Cushing sent a message to SWPA to notify it of the presence of the Japanese prisoners and how they got there. He named them and their ranks as they had provided them (the first on the list was "General Furomei"). The news of the capture of a Japanese general prompted excitement in Brisbane. SWPA general headquarters decided the prisoners must be gotten off Cebu as soon as possible, and it arranged with the U.S. Seventh Fleet at Freemantle to have a submarine stand by for a special mission.

Meanwhile, throughout the morning and afternoon of April 9, Cushing continued to receive reports that Ohnisi's troops were killing civilians and burning villages and that the Japanese were getting closer to him and his captives at Tupas Ridge. Cushing, at midday, informed SWPA that they were going to stage a fake removal from Cebu to withdraw pressure. He added that although the southeast Cebu coast was impossible for a submarine rendezvous, the northeast coast was still clear. He also pleaded for instructions. This message was apparently relayed though Mindanao, then Negros, the island just west of Cebu, and did not arrive in Brisbane until April 12.

After sending off his message, Cushing ordered his camp abandoned. Cushing, the 10 captives, and a small number of guerrillas moved across the broad ravine to near Kamungayan, just over the Tupas Ridge. While there, Cushing received a report that Ohnisi's soldiers had rounded up more than 100 Filipinos, intending to use them as hostages to force the return of the 10 captives. Late that afternoon, hundreds of the Japanese approached the ridges. Cushing had only 25 soldiers.

A firefight ensued. Overhead a Japanese floatplane strafed and dropped antipersonnel bombs on Cushing's forces. Before he withdrew his forces, three of his group, including a nurse, were killed. Cushing led his party away from the Japanese and eventually established a final line of defense. At this point, Cushing learned that more columns of Japanese were marching toward Tupas, leaving burned houses and dead Filipinos in their wake.

With no orders from SWPA, late that evening, April 9, Cushing decided that in order to stop the killing of civilians, he had to make terms with Ohnisi. After informing Fukodome, Cushing quickly drafted a communication to Ohnisi indicating that he had custody of "General Furomei," three officers, and six sailors and that they would be given over to Ohnisi if his soldiers would stop the killing of innocent civilians. Yamamoto translated it into Japanese, and two guerrillas and two prisoners headed toward the Japanese forces with it in hand.

Ohnisi quickly responded, indicating that his operations had been directed toward rescuing "the Japanese Navy Officers that had crashed." He promised that his forces would guarantee the lives and property of Cushing's men and civilians in the event the captives were set free. Within a couple of hours, this message was in Cushing's hand. Still hoping to receive a reply from Brisbane, Cushing decided to stall for time. He sent back a message to Ohnisi saying he would immediately turn over four of the prisoners and the others in a few days as they were too injured to travel. Ohnisi replied "All or no one at all." Cushing went to Fukudome and asked for his personal assurance that the killing and pillaging would stop. Fukudome agreed. Cushing sent a message to Ohnisi that he was sending all the survivors to him at daylight on April 10. Ohnisi replied, acknowledging Cushing's letter and commending him for his "warrior-like and admirable action."

"I expect," he continued, "to see you again in the battle field some day."

Greg Bradsher, an archivist at the National Archives and Records Administration, specializes in World War II intelligence, looted assets, and war crimes. Dr. Bradsher's previous contributions to Prologue have been "Taking America's Heritage to the People: The Freedom Train Story" (Winter 1985); "Nazi Gold: The Merkers Mine Treasure" (Spring 1999); and "A Time to Act: The Beginning of the Fritz Kolbe Story, 1900–1943" (Spring 2002).