Spring 2003, Vol. 35, No. 1

"Incited by the Love of Liberty"

The Amistad Captives and the Federal Courts

By Bruce A. Ragsdale

|

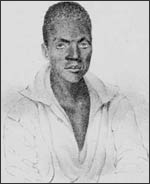

Sengbe Pieh (Cinque), leader of the revolt aboard the Amistad, in an 1839 portrait. (Library of Congress) |

On August 29, 1839, a lone West African man named Sengbe Pieh stood in shackles before a special session of the U.S. District Court for the District of Connecticut. Judge Andrew Judson convened the court of inquiry on board a navy vessel in the harbor of New London, Connecticut.

There the court heard the testimony of two Spanish planters from Cuba. The planters referred to the young African man as Cinque and told the court how he had led a revolt of other enslaved Africans on board the schooner Amistad. Cinque was among a group of fifty-three enslaved individuals whom the planters, Jose Ruiz and Pedro Montes, purchased in Havana and then transported on the Amistad in the direction of plantations along the Cuban coast.

According to the planters, Cinque and his compatriots killed the ship's captain and the cook, then coerced the Spaniards to sail toward the rising sun in hopes of retracing the voyage that had brought them from West Africa.

Cinque spoke neither English nor Spanish and could not testify at the court of inquiry, but his presence dominated the proceeding. In the few short days between being taken into custody by the navy and appearing before the district court, Cinque emerged in press accounts as the near-mythical leader of the revolt on the Amistad.

A reporter who visited him before the court session wrote of Cinque's "uncommon decision and coolness, with a composure characteristic of true courage." The same reporter placed Cinque in a context more familiar to many in the United States by describing him as "a negro who would command in New Orleans, under the hammer, at least $1500."1

When the U.S. attorney in Connecticut drafted an indictment of the captive Africans for murder and piracy, the case entered the docket books of the federal court as United States v. Cinque, et al. Although the criminal charges were soon dismissed, the case title, with its acknowledgment of the critical role of Cinque, signified the distinctive character of the ensuing judicial proceedings related to the Amistad and the enslaved people on board.2

The collection of suits and property claims that forced the federal courts to consider the legal foundations of slavery had come about because of the actions of enslaved individuals, and those individuals appeared in court, represented by lawyers demanding protection of their legal rights. The self-determining actions of the Amistad captives set the case apart from earlier federal cases involving slavery and captured the attention of a nation increasingly divided by debates on slavery and by the sectionalism that would eventually lead to the Civil War. The growth of the antislavery movement in the 1830s and slaveholders' heightened fear of slave revolts gave the court case added import in both the North and the South.

From the time that the Amistad captives arrived in the United States, the drama of their quest for freedom played out within the federal court system.

For many of the Americans who followed the case in the press, the Amistad proceedings were an introduction to the organization and workings of the federal judiciary. The related cases moved through each of the three types of courts in the early federal system and presented issues related to the range of jurisdiction exercised by the federal courts. The progress of Amistad through the federal courts also revealed the paradoxes of a legal culture that simultaneously recognized enslaved persons as chattel and as accountable individuals.

The Amistad case entered the federal judiciary as a familiar type of admiralty proceeding. For several weeks in late summer of 1839, newspapers along the Atlantic coast reported sightings of a mysterious schooner, supposedly controlled by African pirates. The Spaniards' deliberately circuitous navigation had carried the schooner through the Bahamas, along the coast of the United States, and, after nearly two months, into Long Island Sound in search of provisions. The officers and crew of the navy brig Washington confronted the landing party along the New York shore, took custody of the ship and the forty-two surviving Africans and one Cuban slave on board, and then towed the Amistad to New London. Lt. Thomas Gedney and the crew of the Washington contacted the U.S. marshal and requested a hearing in the U.S. district court, where they intended to file a claim of salvage, called a libel, in order to recover a reward for rescuing the badly damaged Amistad and its cargo, including the alleged slaves.3

After Ruiz and Montes testified at the initial court session on board the Washington, Judge Judson transferred the court to the Amistad itself. Antonio, a slave who had served as cabin boy to the slain captain of the schooner, described what he witnessed on the night of the revolt, and he identified the individuals who had led the uprising along with Cinque. Gedney and his crew presented the court with their libel for salvage, with a detailed list of "a large & valuable Cargo." The invoice described such goods as "11 Boxes Crockery & Glassware," "200 Boxes vermacelli," and "800 yds Striped linen" worth, along with the schooner and its fittings, an estimated $40,000. Appended to the list of dry goods was the description of "fifty four Slaves to wit fifty one male slaves and three young female slaves who were worth twenty five Thousand Dollars."4

Judson referred the potential criminal questions to the U.S. Circuit Court for the District of Connecticut. The Judiciary Act of 1789 established the circuit courts to exercise jurisdiction over most federal crimes, over disputes between citizens of different states, and over all but the smallest cases in which the federal government was a party. They also heard some appeals from the district courts. Judson set a date for the U.S. District Court for the District of Connecticut to proceed with consideration of the salvage claim from the officers and crew of the Washington. The district courts were also trial courts with jurisdiction over questions involving maritime commerce and the trade laws of the new nation - the area of law known as admiralty - as well as minor criminal cases and small suits involving the government.5

At the close of the court of inquiry, Judge Judson ordered U.S. Marshal Norris Willcox to take custody of the Africans and to hold them in a New Haven jail pending the next sessions of the district and circuit courts.

Willcox took custody under authority of two warrants. A warrant of seizure, typical of an action in an admiralty case, allowed the government to hold all of the goods in which Gedney and his crew claimed salvage, including the alleged slaves. A warrant of arrest authorized the detention of the Africans who were named in the U.S. attorney's information and complaint as the subjects of a likely criminal indictment.

The court also ordered the marshal to hold Antonio and the three African girls as witnesses in the criminal case. No one responded to the Spanish names Willcox read from the official passes, "it being the names given them at Havanna for the purpose of shipment." The marshal then recorded the names to which they did respond, presumably assisted by Bahoo, the one captive who spoke a very little English.6

The Amistad case almost immediately became the subject of a national debate on slavery and the law. In New York, a group of abolitionists led by Lewis Tappan recognized that the arrest of the Africans presented them with the case they had been seeking in order to challenge the laws of slavery in federal court. Tappan, from a wealthy merchant family, had been an organizing member of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1833. He joined with Joshua Leavitt and Simeon Jocelyn to form a committee that would raise money for the legal representation of the Amistad captives and for their education while in custody. Roger Sherman Baldwin, scion of a prominent Connecticut political family, would lead the legal team with the assistance of Seth Staples and Theodore Sedgwick. In reputation, if not in numbers, they appeared to the U.S. attorney as "an army of counsel."7

In Washington, Secretary of State John Forsyth consulted with the available cabinet members, who agreed that treaty obligations required the United States to deliver the property, including the alleged slaves, claimed by the Spanish government. Forsyth directed the Van Buren administration's response to what he feared might escalate into a diplomatic or political crisis, and he urged the U.S. attorney in Connecticut to do whatever was necessary to keep the captives in federal custody and ready for transportation to Cuba.

The restitution of the claimed slaves would deny a precedent for Great Britain, which in recent years had asserted the right to intercept suspected slave traders in international waters and to free illegally transported Africans. British officials in Bermuda and the Bahamas also had granted freedom to American slaves on board ships that were driven off course during storms. The return of Spanish-claimed slaves was essential if the administration were to assuage southern slaveholders incensed by the British actions.8 Attorney General Felix Grundy drafted an opinion stating that the President had authority to order the marshal to deliver all of the property and the Africans to a representative of the Spanish government. By November, however, when Grundy delivered the opinion, the opening of the trial and the swelling of public interest gave the administration little choice but to follow the judicial process.

"The course of the Executive is decided on," Grundy explained to U.S. attorney William S. Holabird, "but it is deemed expedient to make no communication of it, to any one, until the property is free from all Judicial action, he will then act promptly, in carrying out the opinion of the Attorney General."9

Never before had a federal trial prompted the kind of popular fascination that surrounded the Amistad proceedings. Newspapers detailed the seizure of the Africans and speculated about the role of the charismatic Cinque. A theater on the Bowery in New York City presented a melodrama about "The Black Schooner" and the heroism of "the gallant tars" who rescued the Spanish planters. Inexpensive mass-produced prints celebrated Cinque as "the brave Congolese chief who prefers death to slavery" or as the noble leader who inspired his compatriots.

As the case progressed through the federal courts, traveling exhibits fixed in the public mind a strong visual image of the people and events on the Amistad. A New Haven artist created life-size wax models of twenty-nine of the captives, placed them on a reconstructed deck of the Amistad, and exhibited the display in major cities of the northeastern United States. Another exhibit toured New England with a 135-foot mural depicting the revolt.10

Tappan understood the importance of public opinion and made sure that sympathetic newspapers frequently reported on the condition of the captives and the efforts to instruct them. Racist newspapers devoted just as much attention to the case, with frequent articles mocking the abolitionists and describing the Africans as uncivilized brutes. When the marshal transported most of the captives to Hartford for the sessions of the two federal courts in mid-September, the city was "crowded with strangers, and alive with excitement." "Abolitionists are here, and anti-Abolitionists are here also" to see how the federal courts would deal with the Africans alleged to be both criminals and property.11

The U.S. Circuit Court convened on September 17, 1839, and presented a grand jury with U.S. attorney Holabird's indictment of the adult captives on charges of murder and piracy. With no authorized judgeships of their own, the U.S. circuit courts were presided over by the district court judge and a justice of the Supreme Court. Each justice was assigned to a regional circuit and spent much of the year traveling to the biannual circuit court sessions in the judicial districts; a practice known as "circuit riding."

Justice Smith Thompson of New York, whom James Monroe appointed to the Supreme Court in 1823, joined Judson to preside over the circuit court in Connecticut. Holabird privately doubted the federal court's jurisdiction over an alleged crime that took place on a foreign vessel at sea and thought the evidence insufficient for conviction, but Thompson insisted that the grand jury report a finding of facts before the court would address the question of jurisdiction.12 In the meantime, the abolitionist lawyers challenged the district court's authority to hold the young African girls in custody. Roger Sherman Baldwin, along with Seth Staples and Theodore Sedgwick, secured a writ of habeas corpus and brought the girls before the circuit court to ask for their release on the grounds that the district court lacked authority to detain individuals against whom no criminal charge was made.13

The attorneys argued that to hold these girls under a warrant to seize property, which the marshal cited as his authority, was to force into slavery individuals who arrived in the United States as free persons. In what would be their most important argument throughout the judicial proceedings, Baldwin and his colleagues insisted that the girls, like all of the Africans on the Amistad, were recently and illegally transported to Cuba and never had been held legally as slaves in Spanish territory. Just as the laws of the United States prohibited the slave trade from Africa, so did the treaties and laws of Spain forbid that traffic and declare illegally transported Africans to be free upon arrival in Spanish territory. The captive Bahoo testified in an affidavit that these girls were born in his home village of Bandaboo and had been on the same ship that transported him from West Africa to Cuba the previous spring.14

While Thompson and Judson heard arguments on the habeas writ, the grand jury returned with its finding that the captives had killed the captain and cook on the Amistad and stolen merchandise from the vessel. As most observers expected, Justice Thompson declared that the federal courts had no jurisdiction over any alleged crimes that occurred on the Amistad while at sea. With all criminal charges dismissed by the court, the habeas proceedings took on greater significance.

A second writ brought the adult captives before the court on the same claim that the federal government could not deprive the liberty of individuals who never had been held legally in slavery and who were not charged with criminal activity. The formal answer and reply of the captives asserted that they had been transported and enslaved "contrary to the laws of nature, and of nations, and also contrary to the laws, Treaties and ordinances of Spain." The marshal's return was "insufficient in the law to warrant the caption & detention of them."15

Thompson prefaced his ruling on the habeas writs with unusually personal remarks about his abhorrence of slavery. He said his duty, however, was to determine the proper jurisdiction of the federal courts in this case. He reminded Baldwin and the other lawyers that the Constitution, federal statutes, and decisions of the Supreme Court all recognized the right of one person to control the labor of others and that the federal courts had accepted other foreign claims for slave property.

Thompson denied the request for the Africans' release since they were the subject of legitimate property claims properly submitted to the U.S. district court. The only remaining question of jurisdiction regarded which district court had authority in the case. Thompson declared that it was the responsibility of the district court in Connecticut to determine where the Amistad had been seized and thereby establish which court held jurisdiction in the admiralty proceedings.16

The district court, also meeting in the Connecticut State House in Hartford, convened on September 19, and Judge Judson accepted additional libels filed in response to the salvage libel of Gedney and his crew. Ruiz and Montes each submitted libels asking for the return of all their property, including the alleged slaves, with no deduction for salvage. A group of New York residents who had offered supplies and assistance to the Africans along the Long Island shore filed their own libel for salvage.

U.S. attorney Holabird submitted a libel with alternate requests. He asked the court to consider the Spanish ambassador's claim that the Africans were the slave property of Ruiz and Montes and that the treaty of 1795 between Spain and the United States required the return of all Spanish property in the custody of the courts. If, on the other hand, the court determined that the Africans were not the legal slaves of Spanish planters, Holabird requested that the court order the delivery of the captives to the President for return to their homeland under the terms of an act for the enforcement of the prohibition on the African slave trade.

Holabird's first draft of the libel reveals that he initially defined the court's choice as a question of whether the Africans were slave or free, but he deleted the word "free" and substituted for it the phrase "negroes and persons of colour," equating the Africans' racial identity with some ill-defined status short of freedom. After accepting these libels and ordering an investigation to determine the location where the Amistad was seized, Judge Judson set a trial date for November.17

The fate of the African captives now depended on one judge's decision in an admiralty proceeding. Lewis Tappan understood that if the Africans of the Amistad were to be something other than the objects of competing property claims, they must enter the case as an independent party and testify in the district court.

To enable them to testify, Tappan contacted Yale linguistics professor Josiah Gibbs to study the language of the Africans and recruited Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, the pioneer educator of the deaf, to attempt communication by sign language. Gibbs learned to count in the captives' tongue and set out to find a translator among the many African sailors who worked in the transatlantic trade.

By late September, Gibbs located James Covey and Charles Pratt on a British navy ship in New York. These sailors were from West Africa's Mende region, which the abolitionists then learned was home to the captives from the Amistad. The British commanding officer granted them leave, and the arrival of Covey and Pratt in New Haven allowed the abolitionists to learn the details of the captives' enslavement and to publicize their personal stories.18

The Mende captives formally entered the district court proceedings as respondents during the November session in Hartford. The "several plea" of Cinque and the others challenged the various libels that alleged they were slave property. The plea, submitted by Baldwin and Staples, asserted that the Mende were free-born Africans who in the spring of 1839 had been kidnapped in their native land and illegally sold as slaves in Cuba. "Incited by the love of liberty natural to all men, and by the desire of returning to their families and kindred," the plea explained, they had taken control of the Amistad and later arrived in New York, "a place where Slavery did not exist, in order that they might enjoy their liberty under the protection of its government." The plea maintained that the district court had no authority to detain the Mende, who arrived as free persons in a free state; therefore the captives should "be hence dismissed and suffered to be and remain as they of right ought to be free & at liberty from the process of this Honorable court."19

Spanish officials, with a very different intent, also challenged the authority of the district court to keep the enslaved people from the Amistad in custody. The Spanish consul from Boston submitted his request to take possession of Antonio so that he might be returned to the Cuban heirs of the Amistad captain. U.S. attorney Holabird filed "a separate libel and claim" reaffirming the government's request that the court consider the Spanish ambassador's demand for the restoration of all Spanish property, including "certain slaves." In this libel, Holabird omitted the claim that the Mende might by delivered to the President for return to West Africa.20

In the first testimony of the trial, Judson heard from witnesses who described their encounters with the Mende on the shore of Long Island and others involved in the seizure of the schooner and the Mende. Lawyers for the officers and crew of the Washington tried to establish that the schooner was taken in open seas and that the vessel was so severely damaged that it surely would have been lost if not brought into harbor. The abolitionist lawyers questioned witnesses about the languages spoken by the captives at the initial contact and secured testimony that Ruiz admitted the captives were recently arrived from Africa. Six of the Mende, along with Antonio, were transported to Hartford by the marshal, but they were unable to testify because of the illness of their principal translator, James Covey. After three days, Judge Judson postponed the trial until January 7, when the district court would convene in New Haven and the Mende would be able to present their story.21

Most observers of the proceedings expected that Andrew Judson would not be a sympathetic judge for the Mende. Judson had been appointed to the federal bench by President Andrew Jackson in 1836 and had never ruled on a case related to slavery, but his views on race and slavery were well known in Connecticut.

In 1833, Judson was one of the leaders of a successful campaign to shut down a school established for the education of African American girls in his hometown of Canterbury. He argued that African Americans were not entitled to rights as citizens under the Constitution and publicly stated that African Americans should either be transported out of the country or "kept as they were." He quickly earned the enmity of New England abolitionists, including some members of the Amistad committee.22

Secretary of State Forsyth was so confident that Judson would grant the Spanish demands that he took steps to ensure that the Mende would be on their way to Cuba before the abolitionists would have time to file an appeal. Before the trial reopened in January, Forsyth instructed marshal Norris Willcox to deliver the Mende to a navy ship as soon as the judge decreed their return to Cuba. President Van Buren ordered the U.S.S. Grampus to Connecticut for the purpose, and this vessel, which usually patrolled the coast of Africa to intercept piratical American slave traders, waited off New Haven as the trial progressed.23

On the second day of the January session, Cinque and two other Mende, Grabeau and Fuliwa, testified, and the brief notes in the court records give only a vague sense of the enormous excitement occasioned by their appearance. Speaking through James Covey but punctuating his remarks with powerful gestures and expressions, Cinque described his abduction in Africa, the deadly passage across the Atlantic, and the sale of the captive Mende in Havana.

Following instructions from the judge, who announced he already was convinced the captives were African natives, the attorneys for the Mende focused their examination on the events along the Long Island shore in an effort to answer questions related to jurisdiction and salvage. Lawyers for Gedney raised seemingly irrelevant questions about the captives' lives in Africa and their role in the revolt. In response, Cinque was able to deny the newspaper accounts that he had participated in the slave trade and that he had multiple wives. When the lawyers for the Mende spoke, the crowd "hung upon their lips spell bound," according to the Rev. Henry Ludlow. "At times the feelings of the audience were inexpressible, and they showed their sympathy by external demonstrations of pleasure."24

After five days of testimony and arguments, Judson delivered his decision before a crowded courtroom on January 13, 1840. He first established that his court had proper jurisdiction over the admiralty case, since the Amistad was seized within an area fitting the legal definition of the high seas. He then turned to the salvage questions that had prompted the federal court proceedings. Gedney and the crew of the Washington were entitled to a salvage award for rescuing the Amistad and the merchandise on board, since all would have been lost had the ship continued at sea.

The treaty with Spain allowed charges for "reasonable rates" in returning property, and Judson found that a salvage award of one-third the appraised value of the property was reasonable. Without revealing any decision about the status of the Mende or Antonio as property, Judson denied any salvage award for the enslaved persons on board, since he had no authority to order a sale that would determine a monetary value.25

Judson proceeded to the "great questions" regarding the Spanish insistence on their right to recover the African captives as slave property. The judge acknowledged the unique character of the case when he reminded his listeners that "these Africans come in person, as our law permits them to do, denying this right." The abolitionists' decision to introduce the Mende as parties in the case forced Judson to go beyond the questions of treaties and salvage laws to decide if the Mende were property under Spanish law and, if so, whether Ruiz and Montes held title to that property.26

Judson determined that the planters had no claim to the Africans and, more important, that the Mende were not slave property under Spanish law. The evidence was overwhelming that the Mende arrived recently in Cuba, and under Spanish law any Africans introduced into Spanish territory after 1820 were considered free. Judson refused to order the return of the Mende as demanded by the Spanish. "If, by their own laws, they cannot enslave them," Judson explained, "then it follows, of necessity, they cannot be demanded." At the same time, Judson recognized the authority of the treaty and the right of the Spanish to recover legally held slave property. The judge ordered that Antonio, the legal slave of the Amistad captain, must be returned to the captain's heirs in Cuba.27

Judson's decision that the Mende were free in Spanish territory released the captives from the threat of enslavement, but it did not free them from federal custody. The judge accepted William Holabird's suggestion that the captives be delivered to the President for return to West Africa. Judson acknowledged that the act granting such authority to the President did not apply precisely to the Mende, who were not transported to the United States as slaves, but rather arrived in control of their vessel.

The humanitarian intent of the act, however, was sufficient authority in Judson's mind to decree their delivery to the executive. His moving description of the plight of the Mende gave no indication that he ever considered freeing them immediately or allowing them any opportunity to remain in the country. In the most widely quoted words of the decision, Judson assured his courtroom audience that "Cinquez and Grabeau shall not sigh for Africa in vain. Bloody as may be their hands, they shall yet embrace their kindred."28

"Incited by the Love of Liberty," Part 2

Bruce A. Ragsdale is chief of the Federal Judicial History Office at the Federal Judicial Center in Washington, D.C. He formerly served as associate historian of the U.S. House of Representatives and is the author of A Planter's Republic: The Search for Economic Independence in Revolutionary Virginia (1996).