- Research in Action

- Algorithms for Life

- No Assembly Required

- To See or Not To See...

- A Rare Glimpse Into the Ordinary

- Building Bodily Cancer Defenses

- Addicted to Science

- From the Mountains to the Clinic

- Taking the Long View

- Ambitions of a Tool-Maker

- Teaming Up for Change

- High-Fidelity Stereocilia

- Research into the Realm of Risk

- The Broken Leg Mystery

- Plastic Brains

- Molecular Interventions

- Contacts Far and Wide

- Found in Translation

- Finding the Perfect Target

- Seeing Is Believing

- A Two-year Clinical Research Odyssey

- Immune Coincidences

- An Eye to a Cure

- Energized by Fatigue

- Healthy Body, Sound Mind?

- Principal Investigators

- Scientific Focus Areas

- Our Programs

- Commercializing Inventions

A Rare Glimpse Into the Ordinary

Dr. Han in the laboratory

Joan Han, M.D., points to a photo on her desk showing two 13-year-old boys, both smiling at the camera. The boys are missing part of chromosome 11 and, consequently, suffer from a rare genetic disease called WAGR syndrome. The acronym stands for Wilms’ tumor, a type of kidney tumor; Aniridia, the lack of irises; Genitourinary anomalies; and cognitive impaiRment. When all four symptoms are present, they can represent a significant challenge for any individual or family to manage.

James, a research participant with aniridia caused by a mutation of the PAX6 gene on chromosome 11, testing his visual acuity

A subset of people with WAGR syndrome also suffers from obesity, and it’s this symptom that clearly differentiates the two boys in the photograph. Han, a researcher of pediatric disorders that predispose individuals to obesity, became interested in this rare genetic disease precisely because not all patients display the same set of symptoms—an observation that ignited a multi-year investigation into the childhood obesity associated with WAGR Syndrome, which could subsequently provide insight into the obesity epidemic currently sweeping the world.

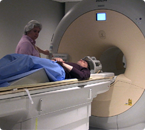

MRI technician Bonita Damaska places James into an MRI machine to image his brain anatomy

It’s been almost 20 years since the discovery of the hormone leptin, a molecule in the brain that activates signals to stop eating and suppresses signals to continue eating. Since then, researchers have pieced together more components of the cascade of signaling molecules involved in the appetite response. One of those molecules is a protein called brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), whose encoding gene happens to reside on chromosome 11, the deleted chromosomal region in WAGR syndrome.

Research assistant Lindsay Hunter using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to determine serum BDNF concentrations, as Dr. Han looks on

“Many scientists are studying BDNF from the neurocognitive perspective—learning, behavior, and degenerative neurologic conditions, like Alzheimer’s disease—but some of us are also studying it from the obesity perspective,” Han says. “We wanted to determine if loss of the BDNF gene might play a role in the obesity observed in WAGR syndrome, and perhaps learn something about the role of this gene in other genetic disorders associated with obesity, like Prader-Will syndrome, as well as for obesity in general.”

Han is an Assistant Clinical Investigator in pediatric endocrinology at the NIH Clinical Center, home to the International WAGR/11p Deletion Syndrome Research Study. As of 2012, the study has collected blood samples over 60 families and carried out evaluations of close to 40 patients with WAGR/11p deletion syndrome on-site at the Clinical Center.

Post-baccalaureate clinical research coordinator Amanda Huey tests James’ sense of smell

Balancing a full-time research commitment with pediatric endocrinology clinic and consultation responsibilities, Han makes the most of the Clinical Center’s collaborative work environment and her colleagues’ expertise in rare diseases. By partnering with other researchers who are interested in the various clinical problems associated with WAGR syndrome, Han’s team also gains access to technical expertise and specialized equipment to investigate additional phenotype-genotype correlations—the relationship between symptoms (phenotype) and specific gene deletions (genotype) for each individual with WAGR syndrome.

Ophthalmic technician Leanne Reuter measuring James’ visual field using a Goldmann Perimeter

“Patients enrolled in our study come from all over the world to see specialists from many different fields, including nephrology, ophthalmology, psychology, neurology, endocrinology, nutrition, rehabilitation, dentistry, audiology, cardiology, gastroenterology, radiology, and genetics—and it’s the combined data from these investigations that inform our research on the role of gene deletions in WAGR syndrome-associated symptoms,” Han explains.

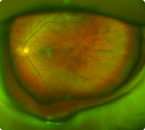

Wide-field fundus photograph of one of James’ eyes

Genetic analyses of patients with WAGR syndrome showed that these individuals have deletions of varying size and location on chromosome 11, some of which include the BDNF gene. These uniquely different deletions partly explain why some people exhibit the classical symptoms of the disease and others show only a subset of symptoms. So, does a missing BDNF gene correlate with obesity?

“In our study, 100 percent of people with BDNF deletion became obese in childhood, compared to only 20 percent of people with intact BDNF, which is similar to the background prevalence of childhood obesity,” Han explains. “This subset of patients with WAGR syndrome has lower serum BDNF concentrations, and since BDNF is an anorexic signal that tells you to stop eating, many patients describe feeling hungry nearly all the time. Families tell us that their children will eat an entire meal and, less than an hour later, are often complaining that they’re hungry again. For some children, it’s a very severe, constant hunger.”

James preparing to determine how much he will eat if presented with a large lunch buffet offering nearly 10,000 calories

Families of people with the BDNF deletion may find hope in a new clinical trial that Han and colleagues are planning with an orally bioavailable BDNF receptor agonist—a drug that increases signaling through the BDNF receptor and could potentially reverse the obesity associated with this genetic deletion.

Working intimately with the families who come to the Clinical Center profoundly affects Han and her team, who strive to answer their questions and relieve the patients’ symptoms. It also motivated Han to expand the research on WAGR Syndrome to pursue broader potential implications for public health, where obesity now affects more than one-third of US adults.

This research is still in the early stages, but initial analyses suggest that common genetic variations of the BDNF gene region are associated with obesity in the general population and that this may be due to a deficit in BDNF expression, a finding that, if verified, could lead to better obesity therapies.

Joan Han, M.D., is an Assistant Clinical Investigator and Head of the Unit on Metabolism and Neuroendocrinology at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

- Text size: A A A

- Get e-mail updates

- Share: