How Susan B. Anthony Became the Most Recognizable Suffragist

A society of patriotic ladies, at Edenton in North Carolina. (Library of Congress)

When I ask my college students to name a suffragist, most of them name Susan B. Anthony. Over a century after her death, many even recognize her picture. In 1979, she became the first woman whose portrait appeared on a circulating coin in the United States. A recent study by the National Women’s History Museum reveals that many states require students to learn about her. Soon, the first statue of historical women in Central Park will feature Anthony and fellow reformers Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Sojourner Truth.

How did Anthony’s face become so visible? Anthony was one of many women’s rights activists, but she was one of the few who dedicated her time to distributing portraits of reformers like herself. Anthony spent significant effort and money to mold the public image of the women’s rights movement.

Anthony borrowed visual strategies from the antislavery reformers, especially from Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth. Douglass and Truth sold their portraits to provide a model of black leadership that countered racist and sexist cartoons. Similarly, Anthony wanted to challenge cartoons that mocked female reformers. She distributed portraits to define the leaders of the movement and emphasize that women—especially well-off white women—could be public leaders, perhaps even president. Anthony’s portraits established a model for female leadership and defined which suffragists we most often remember today.

Bloomerism in Practice (National Museum of American History)

In early America, the public encountered very few printed portraits of women. Women were supposed to prefer the privacy of their homes to public life. While their painted portraits often hung in the homes of wealthy families, engravers rarely copied them to sell to the public. Portraits of George Washington sold, but few women were well-known so their portraits were less desirable.

Additionally, cartoons mocked women who participated in politics. During the American Revolution, artist Philip Dawe satirized women who boycotted tea. This print from 1775, called “A Society of Patriotic Ladies, at Edenton, in North Carolina,” depicts women ignoring a child to focus on their protest. These women are not idealized beauties. One drinks alcohol from a punch bowl. On the right, a black woman—probably an enslaved person—looks like she hopes to sign too. The cartoon demonstrates that women in politics threatened gender norms as well as an economy based on slavery and white supremacy. Printed in London and distributed to the colonies, buyers purchased expensive mezzotints like this one at print shops and from other merchants. They could have posted it in their home or in a gathering place like a tavern.

In 1851, nearly a century later, another print called “Bloomerism in Practice” features a similar critique. The picture was published three years after the Seneca Falls Convention, amidst a wave of similar cartoons that illustrated a backlash against women’s rights activism. In the center of the room, a woman smokes while her husband hunches over to mend clothes. A child cries out for attention, but the mother ignores the child. In the background, a white woman wearing bloomers carries a banner that says “no more basement & kitchen.” Next to her, a black woman’s banner declares “no more massa & missus.” The critique is clear: if women gain rights, society—including gender norms, slavery, class hierarchy, and white supremacy—will be disrupted.

Throughout the 19th century, prints like these were very popular. Americans hung them on their walls, encountered them in cheap newspapers, and discussed them with friends. Reformers like Anthony wanted to prove that these stereotypes of women in politics were wrong, but activists could do little about these pictures. They had weak organizations, very little money, and no control over the popular press.

Fortunately, Anthony could look to her reformer colleagues: Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth. They distributed pictures on their own to raise money. Douglass was one of the most photographed 19th-century Americans. He was born in 1818 and escaped slavery at the age of 20. Soon, he began distributing his portrait, starting with his autobiography. In 1861, the prominent lecturer told audiences in Boston and Syracuse that images could advance racial equality. He said: “the picture plays an important part in our politics and often explodes political shams more effectively, than any other agency.”[1] Although cartoons mocked black people as inferior, Douglass believed that portraits like his—of a refined, elegant black man—challenged stereotypes.

Sojourner Truth must have agreed with Douglass’s strategy. Born in New York in the late 1790s, she also grew up enslaved. She escaped slavery in 1826, a year before the state ended slavery. Truth lectured against slavery, in support of civil rights, and to promote women’s rights.

In the 1860s, Truth started selling a new, popular type of portrait: a carte de visite photograph. These photographs were similar in size to baseball cards, cheap, and everyone wanted them. Americans bought them, exchanged them with friends, and assembled them in photo albums. Truth chose similar poses and clothing each time she sat for her portrait. In this one, she sits in a parlor-like setting with flowers on a table and an open book. Then in her late 60s, Truth looks directly at the viewer. She wears plain, Quaker clothing, a white head wrap, and glasses.

Truth’s portraits challenged racist cartoons, but they also needed to counter sexist ones. She appears respectable. Truth is not interested in frivolous fashions or the controversial bloomer pants. Her right hand grips the tail of her yarn as though she is knitting. Knitting implied that she embraced feminine domestic tasks, but the public portrait revealed that her home was not her sole focus. Poor women and women of color almost always worked to support their families. Truth sold these portraits to make a living.

Anthony thought the portraits of Douglass and Truth were effective. In 1865, she spoke to the Women’s Loyal National League, an organization that Anthony founded to abolish slavery and support the United States during the Civil War. She showed Truth’s portrait to the audience to raise money to support newly freed peoples. She recorded that it was successful.

Anthony sold portraits of herself and her favored female leaders through her newspaper, The Revolution, and her organizations. In 1876, as the nation reflected on its century of history, suffragists decided to write their own. Anthony knew their history needed portraits. She worked with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Matilda Joslyn Gage to produce the History of Woman Suffrage, a series that eventually included six volumes with about 1,000 pages in each.

Anthony managed the portraits. She wrote to suffragists and specified what type of photograph she wanted from them. In an 1882 letter to Elizabeth Boynton Harbert, for example, she clarified that she wanted a portrait that showed “just the head shoulders [sic]” in “about three quarters profile—not a full front—nor yet an entire profile—about halfway between.”[2] Anthony also told Amelia Bloomer, famous for wearing bloomers, to specify which photograph had the “best eyes,” “best hair,” and “best mouth” in order to make the engraving “the best possible.”[3] Anthony hired an expensive engraver to combine all of these best features into a portrait.

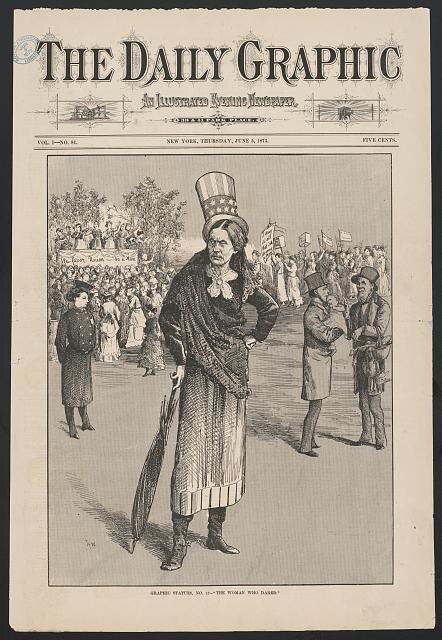

The Woman Who Dared (Library of Congress)

The portraits defined the movement’s leaders as middle- and upper-class white women, a stereotype that persists today. Anthony modeled the portraits after those of leading political men, like presidential candidates. She could have included Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass, but she and other white suffragists distanced themselves from suffragists of color. They thought that if they fought for black women’s voting rights, fewer Americans would support their cause. Many Americans, even reformers, viewed people of color as inferior. For example, in 1869 Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Anthony’s co-editor, referred to black men using the derogatory term “Sambo.”[4] She believed she deserved the vote before they did. Anthony also could have featured white colleagues like Henry Ward Beecher, but she wanted the portraits to make a case for women’s leadership.

As suffragists like Anthony became recognizable, cartoonists started to mock specific women. In 1873, The Daily Graphic, a magazine published in New York, printed this cartoon on its front page. The caption labels Anthony as “The Woman Who Dared.” The editor assumed that viewers would identify her from her popular 1870 portrait that the artist clearly copied. She holds an umbrella the way a general might hold a sword. On the left, a policewoman surveys an all-female rally. On the right, a man holds an upset child, while the other carries a basket with food. Almost a century after the 1775 “A Society of Patriotic Ladies, at Edenton, in North Carolina” cartoon, the artist anticipated that Americans would be entertained enough by the picture to purchase it.

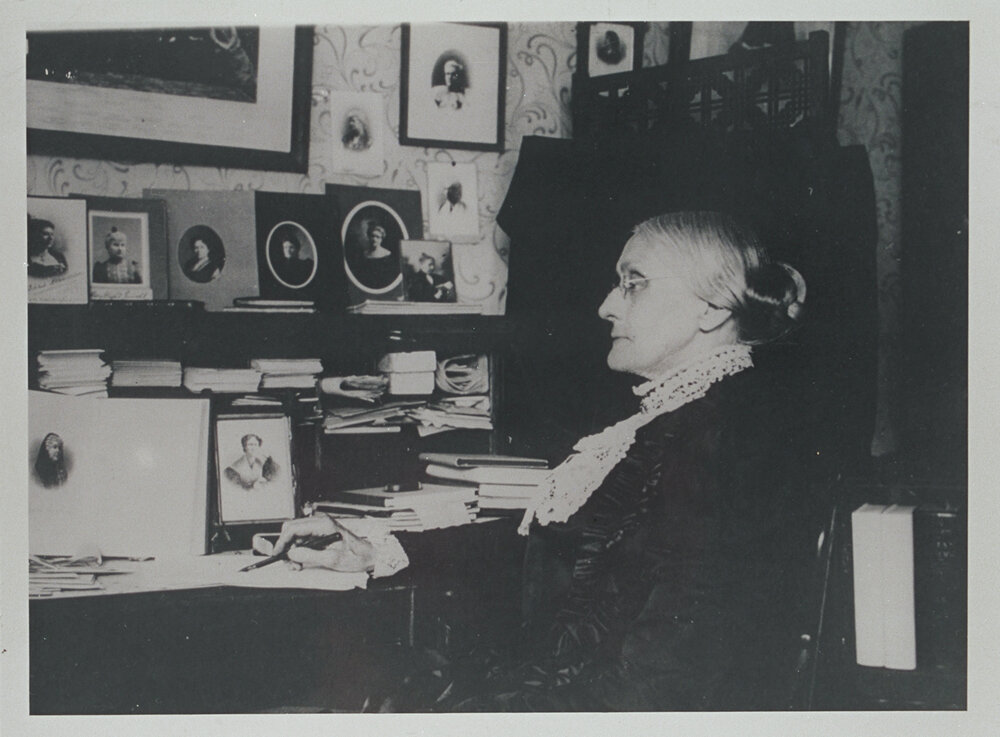

In 1900, Anthony sat for a new portrait. At 80 years old, she is surrounded by her accomplishments. She worked for decades to commission many of the portraits that cover the wall and her desk. Many of them remain familiar today, such as Mary Wollstonecraft, Lucretia Mott, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. She highlighted numerous important women whose faces might have otherwise been lost. We can thank her for the many copies of these portraits in libraries, archives, and museums today.

Susan B. Anthony sitting at desk (Getty Images)

After Anthony’s death in 1906, suffragists turned her into a suffrage saint. Starting in the 1890s, suffragists established national press committees, hired publicity professionals, and founded their own publishing company. They continued to distribute Anthony’s portrait, but they also promoted more traditional ideals of female domesticity. Anti-suffragists still argued that women should not vote because they needed to focus on their homes, so suffragists responded that women needed the vote to improve family life and protect their children. Propaganda distributed by the leading suffrage group, the National American Woman Suffrage Association, often emphasized white women’s roles as mothers. Although leading women of color like Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Mary Church Terrell distributed their portraits, they lacked the resources and support to reach a broad audience.

During the 2020 centennial, we will see many new documentaries, exhibitions, and statues about the history of women’s suffrage. Anthony and the portraits of her favored leaders will probably remain the most familiar. But, now that we know the history behind the movement’s most famous faces, we should highlight less familiar figures too. Susan B. Anthony promoted a vital vision of public female leadership, and we should continue to refine it.

Author Biography

Allison K. Lange is an associate professor of history at the Wentworth Institute of Technology. Her book, Picturing Political Power: Images in the Women’s Suffrage Movement, will be published in May 2020 by the University of Chicago Press. The book traces the ways that women’s rights reformers and their opponents used images to define gender and power in the United States. She is curating suffrage exhibitions at the Massachusetts Historical Society and Harvard’s Schlesinger Library. Lange delivers talks across the country, including at the National Portrait Gallery, Cornell University, and the American Antiquarian Society.

Footnotes

[1] Frederick Douglass, “Pictures and Progress: An Address Delivered in Boston, Massachusetts, on 3 December 1861,” in The Frederick Douglass Papers. Series One: Speeches, Debates, and Interviews., ed. John Blassingame, vol. 3, 1855–63, 1 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985), 457.

[2] Susan B. Anthony to Elizabeth Boynton Harbert, February 4, 1882, in Ann D. Gordon, ed., The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, vol. 4 (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2006), 150–151.

[3] Susan B. Anthony to Amelia Jenks Bloomer, November 30, 1880 in Ann D. Gordon, ed., The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, vol. 4 (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2006), 23.

[4] Elizabeth Cady Stanton to Edward M. Davis, April 10, 1869, George E. Nitzsche Unitariana Collection, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://www.masshist.org/database/3314.A Society of Patriotic Ladies, at Edenton, in North Carolina

Bibliography

Images

“A society of patriotic ladies, at Edenton in North Carolina.” Library of Congress, accessed March 30, 2020, https://www.loc.gov/item/96511606/.

“Bloomerism in Practice.” National Museum of American History, Smithsonian, accessed March 30, 2020, https://www.si.edu/es/object/nmah_326082.

“Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony.” National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian, accessed March 30, 2020, https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_S_NPG.77.48?destination=edan-search/default_search%3Freturn_all%3D1%26edan_q%3Dsusan%2520b.%2520anthony.

“Frederick Douglass.” National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian, accessed March 30, 2020, https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_S_NPG.91.75?destination=edan-search/default_search%3Freturn_all%3D1%26edan_q%3Dfrederick%2520douglass.

“Image 2 of Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass, an American slave.” Library of Congress, accessed March 30, 2020, https://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbcb.25385/?sp=2.

“Sojourner Truth. I sell the shadow to support the substance.” Library of Congress, accessed March 30, 2020, https://www.loc.gov/resource/lprbscsm.scsm0880/.

“Susan B. Anthony Sitting at Desk.” Photo by Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images. Getty Images, accessed March 30, 2020, https://www.gettyimages.com/photos/susan-b.-anthony-1900?mediatype=photography&phrase=susan%20b.%20anthony%201900&sort=mostpopular.

“The Woman Who Dared” in The Daily Graphic. Library of Congress, accessed March 30, 2020, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/ppmsca.55836/.

Selected Texts

“Where are the Women? A Report on the Status of Women in the United States Social Studies Standards.” National Women’s History Museum, accessed March 30, 2020, https://www.womenshistory.org/social-studies-standards.

Blassingame, John, ed. The Frederick Douglass Papers. Series One: Speeches, Debates, and Interviews, vol. 3, 1855–63, 1. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985.

Gordon, Ann D., ed. The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, vol. 4. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2006.

Lange, Allison K. Picturing Political Power: Images in the Women’s Suffrage Movement. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020.

Lemay, Kate Clarke, ed. Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019.

Painter, Nell Irvin. Sojourner Truth: A Life, a Symbol. New York: W.W. Norton, 1997.

Stauffer, John, et. al. Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century’s Most Photographed American. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2015.

Tetrault, Lisa. Myth of Seneca Falls: Memory and the Women’s Suffrage Movement, 1848-1898. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

Ware, Susan. Why They Marched: Untold Stories of the Women Who Fought for the Right to Vote. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press: An Imprint of Harvard University Press, 2019.