At the turn of the last century, conditions for children in America looked very different from today. More than 1 in 10 infants did not survive their first year. Many children left school to help support their families, often working in dangerous conditions. Orphans were crowded into large institutions, where they received little care or attention.

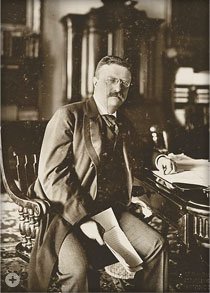

Lillian D. Wald, founder of the Henry Street Settlement in New York City, and her friend Florence Kelley are credited with conceiving the idea for a Federal agency to promote child health and welfare in 1903. Impressed with the idea, a friend of Wald’s wired President Theodore Roosevelt, who promptly invited the group to the White House to discuss it further. The journey to create the Children’s Bureau had begun.

Many years of nationwide campaigning by individuals and organizations followed. Eleven bills, eight originating in the House and three in the Senate, met with failure between 1906 and 1912. In 1909, President Roosevelt convened the first White House Conference on Children. This meeting brought together social workers, educators, juvenile court judges, labor leaders, and other men and women concerned with children’s well-being, who collectively endorsed the idea of a Federal Children’s Bureau.

“There are few things more vital to the welfare of the Nation than accurate and dependable knowledge of the best methods of dealing with children...” - President Theodore Roosevelt

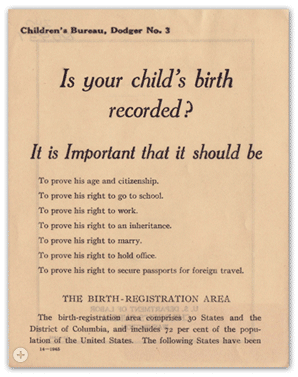

In 1912, Congress passed the Act creating the Children’s Bureau and charged it “to investigate and report . . . upon all matters pertaining to the welfare of children and child life among all classes of our people.” President William Howard Taft signed the bill on April 9, 1912. The bill included an initial appropriation of $25,640.

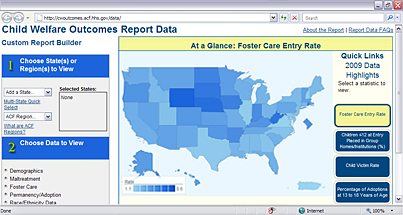

Link:

Establishment of the Bureau (1912) PDF - 842.50 KB