- Research in Action

- Forces of Nature

- Mining for Cancer Insights

- Algorithms for Life

- No Assembly Required

- To See or Not To See...

- A Rare Glimpse Into the Ordinary

- Building Bodily Cancer Defenses

- Addicted to Science

- From the Mountains to the Clinic

- Taking the Long View

- Ambitions of a Tool-Maker

- Teaming Up for Change

- High-Fidelity Stereocilia

- Research into the Realm of Risk

- The Broken Leg Mystery

- Plastic Brains

- Molecular Interventions

- Contacts Far and Wide

- Found in Translation

- Finding the Perfect Target

- Seeing Is Believing

- A Two-year Clinical Research Odyssey

- Immune Coincidences

- An Eye to a Cure

- Energized by Fatigue

- Healthy Body, Sound Mind?

- Principal Investigators

- Scientific Focus Areas

- Our Programs

- Commercializing Inventions

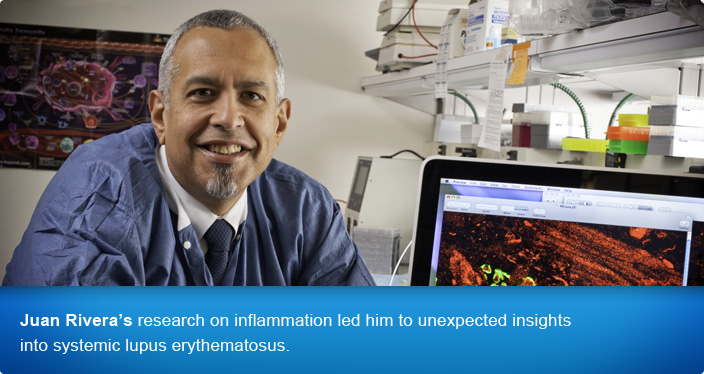

Immune Coincidences

Juan Rivera, Ph.D., did not set out to study lupus, let alone take part in developing a pilot clinical trial for its treatment. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease resulting from the production and accumulation of antibodies targeting the body’s own nucleic acids and proteins. This antibody accumulation in the kidney results in lupus nephritis, which may rapidly produce kidney failure. The Rivera lab studies a much different aspect of immune dysfunction—the molecular events that promote chronic inflammation seen in allergies and autoimmune disorders like rheumatoid arthritis.

“Since its inception,” said Rivera, a 35-year veteran of the NIH, “my laboratory has been focused on understanding the role of Fc receptors in health and disease.” Fc receptors are found on the surface of many immune cell types; they bind to antibodies that have latched on to perceived pathogens and trigger cellular immune responses that normally help to eliminate the pathogen.

Many Fc receptors are associated with a signaling enzyme coded by the gene Lyn. In pursuit of the molecular and cellular mechanisms of Fc receptor function, Research Fellow Nicholas Charles, Ph.D., decided to study a mouse lacking both copies of the Lyn gene. Although, it was known that in such mice, a lupus-like condition develops late in life, Rivera’s team first observed that the mice developed allergic sensitivities at an early age.

“It was quite striking that in early life, this mouse developed an allergic phenotype and then later, it developed an SLE-like phenotype,” said Rivera. “The question for us became: Are these two things related?”

Rivera’s team discovered that the source of the early allergic sensitivities was dysregulation of basophils, a type of white blood cell known to be involved in inflammation. When they depleted the basophils or altered their mouse model to genetically interfere with the molecular signals that basophils secrete, the mouse reverted to normal.

“Then, we essentially aged the mice we had generated,” said Rivera. To their surprise, they found that basophils were also playing a role in the development of the mouse version of SLE. The same manipulations of basophils that prevented allergies also alleviated the SLE-like symptoms. To Rivera and his team, it appeared that the basophils were communicating with other cells to amplify autoimmune antibody production.

Specifically, they proposed that in this mouse, an initial production of autoimmune antibodies—specifically autoreactive IgE antibodies—generates a positive feedback loop. These antibodies form complexes that bind and activate basophils, causing the basophils to migrate to lymphoid organs and provide factors to cells that support further antibody production.

Immediately, of course, the researchers wondered whether basophils could be playing a role in the human disease. Collaborating with NIH colleague Gabor Illei, M.D., Ph.D., M.H.S., Rivera and his team were able to show that patients with SLE also have autoreactive IgE antibodies and activated basophils associated with the higher disease activity and, in particular, with lupus nephritis.

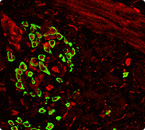

Working with Eric Daugas, M.D., Ph.D., at the Université Paris Diderot, Rivera obtained rare biopsy samples from patients with SLE and verified the presence of basophils in lymphoid organs, where they are not normally seen. “We are continuing to acquire samples to get a much better assessment of the immunological and clinical features of activated basophils in SLE,” said Rivera.

“Our findings suggest that the heterogeneity one sees in lupus may be defined by how these cellular networks in the immune system are interacting with each other,” said Rivera. It also suggests a novel therapeutic strategy for the disease. The drug omalizumab specifically lowers circulating IgE levels and decreases expression of the Fc receptor on basophils; it is approved for treatment of severe allergic asthma. The team is designing a pilot safety study to test the possibility that omalizumab may be effective in some forms of lupus.

Juan Rivera is Deputy Scientific Director and Chief of the Laboratory of Molecular Immunogenetics in the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS).

Further reading:

- Text size: A A A

- Get e-mail updates

- Share: